The Jesus We Never Knew

The October 2000 issue of The Atlantic Monthly featured a perceptive, and, to many, a surprising essay on the renewal of evangelical thought and scholarship. In 'The Opening of the Evangelical Mind,' Alan Wolfe interviewed important evangelical scholars and others and found that many evangelicals and significant institutions have stepped up to the intellectual plate. Stereotypes of backwoods, simplistic, and monosyllabic believers desperately trying to pretend it was still the 1950s, loudly crashed right and left.

Many in my circle of evangelical academics and students were buzzing and beaming about this unexpected article. Wolfe found that some evangelicals are writing scholarly books that appeal to those outside the fold. And they are participating in learned associations and even forming new ones, such as the influential Society of Christian Philosophers.

Many of us evangelicals are trying to put the lie to Bertrand Russell’s famous quip that 'Most Christians would rather die than think—and most do.' Despite persistent stereotypes to the contrary, Wolf deemed these evangelicals—not all, of course—an intellectual force worth reckoning with, however much they still battle against the antiintellectualism of their past. Wolfe concluded that for evangelicals to be accorded more respect intellectually, they need to drop their defensiveness and engage the intellectual community more broadly.

Enter Jesus

Conspicuously absent, however, from Wolfe’s evaluation—and absent as well from the observations of the leading evangelical minds he consulted—was any reference to the intellect of the founder of Christianity itself: Jesus of Nazareth. Yet in this ever-controversial and world-historical figure we find an intellect keenly engaged in the great controversies of his day—and in many of ours as well. He intellectually engaged everyone in sight. Any Christian would do well to return to the sources of their faith in the Gospels and take one more close look at the one who animates them. Even those outside Christian communions may be surprised and delighted to find in Jesus a bona fide philosopher who held a developed worldview and employed careful patterns of reasoning on consequential matters.

Although I have long reflected on the Gospels, and have written books on Jesus, I was first challenged to consider Jesus as a philosopher when secular philosopher Daniel Kolak asked me to write a book on Jesus for the Wadsworth Philosophers Series, which he is editing. Kolak, an ecumenically-inclined unbeliever, included Buddha, Lao Tze, and Confucius in this series. In writing On Jesus, I applied philosophical categories to the teachings of Jesus and not those of standard works of biblical scholarship or theology—although these disciplines cannot be avoided entirely. So, I looked at Jesus’ patterns of general argument (which I found surprisingly varied and adroit), his metaphysics, his ethics, his epistemology (theory of knowledge), and his outlook on women. I also addressed the arguments he made on behalf of his own purpose and identity. What I encountered was that Jesus could not be disqualified from the ranks of the philosophers. He never flinched from a good debate and used clever and effective arguments in his disputes. Moreover, he held views not readily granted by even many Christians’particularly regarding the value and contributions of women. And unlike some Christians today, he never devalued the intellect in favor of 'faith.' I find nothing in the Gospels about any 'leap of faith.'

The Jesus I encountered was not found through the methodology of radical, cut-and-paste biblical criticism or the deconstruction—or excavation—of a Jesus according to an avante-guard theory (as challenging as those sometimes may be). I simply tried to read the Gospels through the eyes of a philosopher. What I found was nothing less than a philosopher—although many would argue much more than a philosopher as well.

Was Jesus a Philosopher?

We cannot proceed further in answering our question, 'Was Jesus a philosopher?' without thinking more clearly about the term 'philosopher.' What qualifies someone as a philosopher? We can certainly point to uncontroversial specimens, such as Plato and Aristotle. But what of harder cases, such as Jesus? Of course, philosophers philosophize, but not everyone who philosophizes is a philosopher, just as not everyone who works on an automobile is a mechanic. We think of most philosophers as intelligent, but not all the intelligent are philosophers. Many individuals’ intelligence may not be invested primarily in philosophy. Neither can we limit the philosophers to those who are formal academics. Some philosophers, such as Hume, Spinoza, and Pascal, have lacked institutional affiliation, but not philosophical credentials.

I propose that required conditions for being a philosopher are a strong and lived-out inclination to pursue truth about philosophical matters through the rigorous use of human reasoning, and to do so with some intellectual facility. The last condition is added to rule out those who may fancy themselves philosophers but cannot philosophize well enough to merit the title. Even a bad philosopher must be able to philosophize in some recognizable sense. By 'philosophical matters' I mean the enduring questions of life’s meaning, purpose, and value. Yet one may speak to life’s meaning, purpose, and value in a nonphilosophical manner—by merely issuing assertions or by simply declaring divine judgments with no further discussion. A philosophical approach to these matters, on the contrary, explores the logic or rationale of various claims about reality; it sniffs out intellectual presuppositions and implications; it ponders possibilities and weighs their rational credibility.

Therefore, the work of a philosopher need not include system-building, nor need it exclude religious authority or even divine inspiration so long as this perspective does not preclude rational argumentation. Being a philosopher requires a certain orientation to knowledge, a willingness to argue and debate logically, and to do so with some proficiency. We find this in Jesus, despite his strange exile from the realm of the philosophers. I will illustrate this by discussing his teachings on the ethics of virtue and the relation of virtue to knowledge.

Jesus and the Virtues of the Kingdom

Jesus is profoundly concerned with the character or inner disposition of people as they relate to God, others, and creation. In this, he profoundly challenges some commonly held beliefs about character and sexuality. In so doing, he should stir up some philosophical lines of thought that otherwise might lie go unheeded.

Jesus is not unlike the Hebrew prophets who often spoke of internal motivations and beliefs. Jesus’ beatitudes stress attitudes that Jesus pronounces 'blessed,' or objectively good, right, and in harmony with God’s ways. 'Blessed' is not synonymous with our meaning of 'happy'—a subjective state of pleasure or enjoyment. Jesus says that those who are 'persecuted because of righteousness' are blessed (Matthew 5:10), as are 'those who mourn' (Matthew 5:3). Therefore, mere happiness is not in view, but something deeper.

Jesus’ account of virtue is profoundly theological and teleological. Unlike a modern virtue theorist such as Iris Murdoch, who says we must be literally 'good for nothing' (since there is no God, no afterlife, and no necessary causal relationship between virtue and felicity), Jesus places the virtues into a cosmic and supernatural framework, that of 'blessedness.' These character traits do not merely exhibit objective moral properties (Murdoch’s view), they fit the world and the people God has created. Jesus’ account of virtue is similar to Aristotle’s correlation of virtue and telos (cosmic purpose), where proper conduct is conducive to human flourishing. But Jesus’ view is dissimilar as well, since Aristotle’s philosophy allotted the Prime Mover no ethical role in establishing, announcing, or rewarding moral character. For Jesus, God is central to the nature and experience of virtue.

The Sermon on the Mount, from which the beatitudes are taken, repeatedly concentrates on the 'heart'—which referred to the deepest and central reality of the person (not merely the emotional center). Here Jesus makes some stinging claims worth considering. While Jesus does not set aside the Hebrew law, he radicalizes it and applies it in some disturbing ways. Jesus reminds his hearers that they have been taught, 'Do not murder, and anyone who murders will be subject to judgment.' But he goes beyond this to say, 'Anyone who is angry with a brother or sister will be subject to judgment,' as will anyone who uses abusive language against another. Therefore, one should make peace with others before giving religious offerings (Matthew 5:21-24). Jesus does not condemn all manner of anger, but the dangers intrinsic to anger, such as revenge, viciousness, and so on. Jesus himself unapologetically used a whip to clear the temple of its religious profiteering and spoke harshly of religious hypocrisy. In teaching people who already knew the moral law against committing adultery, Jesus adds, 'But I tell you that anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart.' Therefore, one should take radical action to avoid such harmful fantasies. Speaking hyperbolically, Jesus says to gouge out the offending eye and to cut off the offending hand (Matthew 5:27-30).

Philosopher Michael Martin in The Case Against Christianity rightly notes that 'Jesus’ emphasis on controlling one’s thoughts, emotions, and desires has been deemphasized and in many cases nearly eliminated from modern discussions of Christian ethics.' Yet he rejects these strictures as impractical and unwise, alleging that 'if Jesus’ injunction is interpreted as a command not to contemplate any evil actions at all, it has been maintained that it thwarts our imagination and forbids the contemplation of evil, for example, in art and literature.' Martin thinks such contemplation really discourages evil instead of encouraging it.

Jesus’ injunctions against anger and lust should not be viewed as forbidding even the fictional portrayals of these emotions. Jesus’ own parables describe wicked or foolish people who are not models of good character. Rather, Jesus’ teaching disallows adopting an inner orientation that countenances, values or plays out the vices he mentions. Reading an account of an evil character in The Brothers Karamazov, for example, would not violate Jesus’ injunction. Wanting to emulate this character—or Milton’s Lucifer’would violate Jesus’ teachings, whether or not one ever acted out the imaginations.

Martin then considers whether Jesus’ prohibition could be justified on the grounds that such angry or lustful thoughts might lead to actions involving deleterious consequences. He grants this is sometimes the case, as when 'sexist language has indirectly harmful effects on women,' but he discards Jesus’ standards as too imposing and not warranted. Martin thinks that Jesus 'may well have believed that certain thoughts or emotions were bad in themselves independent of their consequences.' Martin disagrees, because he deems consequences to be the determining factor in ethics. 'Emotions, desires, thoughts, and feelings do not seem to be good or bad in themselves.'

Martin seems to have a utilitarian standard of moral evaluation in which the status of actions counts more than the character of persons. Utilitarianism is subject to many criticisms, but it suffices to say that many virtue theorists count certain inner states as having inherent moral value whether or not they produce actions, although in many cases they should produce actions. There is a moral obligation to be a particular kind of person, regardless of whether this results in external actions in every case. Virtues are more than dispositions to act, since they may obligate one to attain and maintain certain inner states or ways of being, which are good in themselves. Jesus is not alone in his view of the moral status of inner states, although he puts his case more strongly than most contemporary ethicists would.

To illustrate the complementary view of virtue, consider which person you would rather have for a friend or would value more highly morally. William acts caring and respectful, but he entertains unduly angry thoughts toward you quite often, although never expresses them. George acts caring and loving to the same degree as William, but never has these angry thoughts about you. If you would pick George over William, Jesus’ basic point is supported. Thoughts and attitudes do matter ethically.

British philosopher Roger Scruton argues in An Intelligent Person’s Guide to Philosophy that sexual fantasizing is morally out of place because it devalues persons. Instead of deeming persons as objectively existing others, lust replaces persons with compliant images subject to one’s arbitrary mental manipulation. 'The fantasy blocks passage to reality.' The 'fantasy Other,' who is completely the instrument of one’s imagination, becomes merely an object to the one fantasizing. 'The sexual world of the fantasist is a world without subjects, in which others appear as objects only.' Scruton argues that the very mental act of such fantasies is an exercise in unhealthy and disrespectful unreality. One might call it psychic rape. (Scruton believes that if the fantasist becomes possessed by this image, rape is the natural result.) He thus provides a gloss on Jesus’ own teaching—and a fitting counterpoint to Martin’s utilitarian, nonvirtue approach.

Jesus on Knowledge and Character

In recent years, philosophers have begun to rediscover the role of moral character in epistemology, not merely in ethics proper. Philosophers still rightly ask what makes beliefs qualify as knowledge (truth plus justification or warrant), but more philosophers are now asking what makes believers good candidates for knowledge. What qualities best suit a person for attaining knowledge? What traits taint a person’s capacity to know what ought to be known? This is called virtue epistemology; it has a long pedigree going back to Aquinas and Augustine in the Western tradition. Intellectual virtues have classically included qualities such as patience, tenacity, humility, studiousness, and honest truthseeking. Vices to be avoided include impatience, gullibility, pride, vain curiosity, and intellectual apathy.

There is a strong emphasis on character—both virtue and vice—in Jesus’ epistemology, which is closely intertwined with his teachings on ethics and the knowledge of God. He not only gives arguments and tells parables, he calls people to intellectual rectitude and sobriety. Jesus’ familiar moral teaching about the dangers of judgmentalism contains an epistemological element easily overlooked.

Do not judge, or you too will be judged. For in the same way as you judge others, you will be judged, and with the measure you use, it will be measured to you. Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in someone else’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your own eye? How can you say, ‘Let me take the speck out of your eye,’ when all the time there is a plank in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from the other person’s eye. (Matthew 7:1-5).

This passage is often taken out of context to forbid all moral evaluation, as if Jesus were a relativist. But Jesus has something else in mind: a clear-sighted self-evaluation and a proper evaluation of others based on objective standards. Jesus stipulates that all moral judgments relate to the self as much as to the other. Therefore, when one judges others, one is implicitly bringing oneself under the same judgment. One will be measured by the same measurement one employs. In light of that, a person needs first to search her or his own being for any moral impurities and seriously address them ('take the plank out of your own eye'). Only then is one in a good epistemological and ethical position to evaluate another, to 'see clearly' the speck in someone else’s eye.

If one fails to evaluate oneself by one’s own standard, one cannot rightly discern the moral status of others. In other words, proper moral evaluation requires a knowledge of the self, and allows no special pleading. The hypocrite is not only morally deficient, but epistemologically off-base as well. By failing to be subjectively attentive to one’s conscience, one fails to discern moral realities objectively. Thus people will often condemn others overly because they ignore or obscure their own transgressions.

Jesus gives further incentive to evaluate situations justly—that is, to be virtuous knowers—when he warns that people will be held accountable before God for every word they utter. Their judgments issue from their character, and their character will affect their destiny.

Good people bring good things out of the good stored up in them, and evil people bring evil things out of the evil stored up in them. But I tell you that people will have to give account on the day of judgment for every careless word they have spoken. For by your words you will be acquitted, and by your words you will be condemned. (Matthew 12:35-37)

Jesus sometimes deemed the character of his hearers as interfering with their ability to know and apply the truth of his words and actions. In a quarrel over his own identity, Jesus accused his hearers of not understanding their own Scriptures or the testimony that John the Baptist gave on Jesus’ behalf. Nor did they have 'the love of God in their hearts.'

I have come in my Father’s name, and you do not accept me; but if others come in their own names, you will accept them. How can you believe [in me] if you accept praise from one another, yet make no effort to obtain the praise that comes from the only God? (John 5:43-44)

One might think this is an ad hominem fallacy. Jesus is attacking the person, not the argument. But Jesus does not replace an argument with a negative assessment of character; rather, he explains their inability to believe in him according to their over-concern with social status, which precluded their seeking truth. Giving more evidence or arguments does not serve Jesus’ purpose here; instead, he ferrets out their character defect and its epistemological consequences. Such sagacious character assessments would go a long way in our own day, whether in politics, the arts, or everyday life.

Jesus also advises endurance in seeking knowledge (and virtue), by giving hope that the world is intelligible and penetrable to those with the proper disposition. Consider this statement in the Sermon on the Mount concerning persistence in seeking.

Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives; he who seeks finds; and to him who knocks, the door will be opened. (Matthew 7:7-8)

The best things in life may not be easy to find, despite what we hear otherwise in advertising and politics. Jesus challenges his audience to develop a diligence wisely calibrated to the urgency and consequences of the great questions.

Jesus’ Surprising View of Women

Another aspect of Jesus’ teachings that many may find surprising is that he did not ape the patriarchy of his day; in many ways, he creatively subverted it. Although much has been made of the fact that he did not select any women to be among the twelve apostles, Jesus had a high view of women—arguable the highest view of any religious founder in history.

In the ancient context of Jesus’ day, women typically had little social or cultural influence. Their roles were usually limited to domestic life, and in the home and family they had very little control over money or possessions apart from their fathers or husbands. A Jewish man would pray three benedictions each day, one of which thanked God for not making him a woman (although nothing like this is contained in the Hebrew Scriptures). Within this cultural context, Jesus’ respectful regard for women was unusual and sometimes even scandalous to those around him.

Jesus did not annul family relationships, but he refused to endorse the common idea that women exist solely to be mothers and wives in the home. After Jesus gave a lesson about evil spirits, a woman from the crowd called out, 'Blessed is the mother who gave you birth and nursed you.' Jesus replied, 'Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and obey it' (Luke 11:27-28). Instead of reinforcing the idea that motherhood is the primary or overriding purpose of women, Jesus put more value on being attentive and obedient to God’s word. This is an implicit endorsement of the right of women to be taught, which was not usually permitted in ancient Jewish circles.

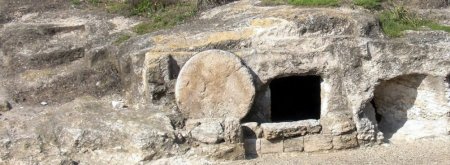

The Gospels report that women were among his close followers. Martha and Mary have already been mentioned. A group of women—Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Susanna and others—listened to Jesus and traveled with Jesus and his male disciples. 'These women were helping to support them out of their own means' (Luke 8:1-3). The faithfulness of Jesus’ female disciples was most notable during the last days of his ministry. Unlike most of the male disciples, the women who followed Jesus were at the crucifixion (Matthew 27:55-56). Jesus’ burial was witnessed by at least two women, Mary Magdalene and 'the other Mary' (Matthew 27:61). All four Gospels report that women—including Mary Magdalene, 'the other Mary,' and Salome—were the first to discover the empty tomb and to proclaim Jesus’ resurrection to the initially unbelieving male disciples.

Jesus referred to women as worthy examples in many of his teachings. In Luke chapter 15, Jesus tells three parables about God’s rejoicing over repentance. One features a woman whose rejoicing reminds us of God’s response to the contrite.

Or suppose a woman has ten silver coins and loses one. Does she not light a lamp, sweep the house and search carefully until she finds it? And when she finds it, she calls her friends and neighbors together and says, 'Rejoice with me; I have found my lost coin.' In the same way, I tell you, there is rejoicing in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner who repents. (Luke 15:8-10)

Jesus’ affirmation of women as students of religious instruction is made clear in the account of the sisters Mary and Martha, close associates of Jesus. After inviting Jesus and his disciples into their home, Mary sat at Jesus’ feet listening to his teaching. Martha was distracted by all her chores of hospitality and said to Jesus, 'Lord, don’t you care that my sister has left me to do the work by myself? Tell her to help me!' Jesus replied, 'Martha, Martha, you are worried and upset about many things, but only one thing is needed. Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her' (Luke 10:38-42). Jesus does more than tell Martha not to be so hyperactive. He endorses Mary’s right to be taught, remarking that this is more important than the traditional province of a woman (preoccupation with domestic tasks).

In the account of the death of Martha’s brother, Lazarus, the same woman that Jesus had corrected for not listening to his teaching now affirms a vivid theological doctrine about him. In a discussion with Jesus about life, death, and resurrection, Martha makes a declaration very similar to the one given by the Apostle Peter (Matthew 16:16). She says, 'I believe that you are the Christ, the Son of God, who was to come into the world' (John 11:27). She here gives one of the strongest statements of messianic faith in the Gospels, and so becomes a model of theological veracity and rectitude.

But some argue (or worry) that since Jesus did not invite women into his inner circle of Apostles, he did not deem them worthy or capable of the highest levels of leadership and responsibility. This idea ignores the limits of Jesus’ cultural context. Given the highly patriarchal setting of Jesus’ ministry, it would have been unlikely if not culturally impossible for him to have operated effectively with women in his innermost circle. Biblical scholar David Scholer notes that it 'is remarkable and significant enough that women, at least eight of whom are known by name and often with as much or more data as some of the Twelve, were included as disciples and proclaimers during Jesus ministry.' Scholer also observes that the original Jewish apostles did not continue to serve as the models for church leadership after the earliest days of the church at Jerusalem. Faithful Gentiles could be leaders as well. Moreover, despite a few local restrictions on women in some settings, there is strong evidence for women serving in leadership during the New Testament period. This is no surprise, since Jesus knew women to be far more than their immediate culture ever allowed.

Reconsidering the Jesus We Never Knew

The Jesus we never knew was a thinker (even a philosopher) and moral reformer who did not bow down before the status quo nor accommodate moral mediocrity. He did not place blind faith over God-given reason. He did not place men over women. He also laid claim to the unique theological prerogatives that we may be more used to thinking about.

Although the Gospels report Jesus as speaking with a divine prerogative, he also argued logically for his views in the face of considerable and well-schooled opposition. He did not evade, equivocate, posture, or propagandize. His view of politics and religion, of virtue and knowledge, of women’s significance, and much else are quite telling and of contemporary pertinence, whether one is religious or not. Perhaps it is time to open the Gospels once again, in order to bring new questions to ancient texts, and possibly to discover unexpected answers.