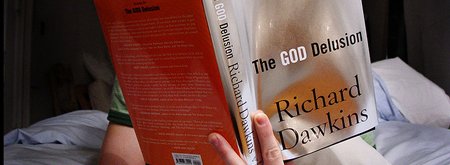

The Root of all Evil? - The problem with Dawkins' faith

Nick Pollard reviews Richard Dawkins' two part Channel 4 TV programme The Root of All Evil?

Richard Dawkins is the Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. He is an enthusiastic advocate of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. But he doesn’t just stop there. He goes further to argue that an alternative belief in divine creation is not only untrue but also deeply damaging to people and to our world.

He has expressed that view in many lectures and books. Indeed, in my own interview with him, he spoke of the ‘evils of theism’. But he has particularly brought this attack on religious belief into popular culture in the first of his two-part series for Channel 4, called The Root of all Evil?[1] In this programme he sought to show that although religions may preach morality, peace and hope, in fact they bring intolerance, violence and destruction. Therefore, he said, ‘the war between good and evil is really just the war between two evils.’ In an attempt to provide evidence for this assertion, he talked to a number of believers in the three Abrahamic faiths – Judaism, Islam and Christianity. So we moved from film of desperate people in Lourdes to a dogmatic church in America, then on to Jerusalem where we encounter fundamentalist Jews and Muslims.

No doubt many scientists watching the programme (particularly those experienced in social science) were a little embarrassed that this Professor of the Public Understanding of Science was seeking to justify his assertion with such an obviously restrictive and carefully selected sample-set. If one really wanted to establish the effects of religion, one would need a much broader and more representative set of data than this. Meanwhile, no doubt many Christians were praying that somehow they could show him how their experience of Jesus has led them to a greater morality, peace and hope. But even if we accept the data as he presented it, and consider his ideas as he asserted them, it would seem that once again Dawkins had fallen into some of his usual logical fallacies.[2]

For our purposes here, let’s just consider one of these: the logical fallacy known as ‘Self Contradiction’ – a statement cannot be true if it contradicts itself. For example, imagine I tell you that, ‘I cannot speak a word of English.’ That statement cannot possibly be true since I am speaking English in order to make the statement. Thus the statement contradicts itself and cannot be true. When Dawkins argues that we evolved through survival of the fittest and that religious belief is evil, he too is contradicting himself. But we have to look a little more carefully and deeply in order to see that.

When he claims that religious belief is evil, he must assume that a moral right and a moral wrong actually exist, and that evil is a real and meaningful concept. But can he do that if he believes that we have evolved through unguided, undirected natural selection of random mutations? Or do the concepts of right, wrong, good and evil actually only make sense if God exists?

This is sometimes expressed in what is called the ‘Moral Argument for God’ which might be given as follows:

- Activities such as torturing babies for fun are objectively morally wrong and we really ought not to do them

- Therefore, because of this and other examples, we can know that there are certain things that are objectively morally wrong and we really ought not to do them

- Now, let’s unpack the three concepts in that sentence: the concepts of morally wrong, objectively and ought.

– If there is something that is morally wrong, then there must be a moral law-giver – an activity cannot be right or wrong without someone or something that is outside or inside of us declaring it to be right or wrong

– If the right or wrong is objective, then the moral law giver must be outside of ourselves and must be infinite – the fact that it is objective means that it goes beyond individual human preference, personality or culture, and therefore cannot be finite like us human beings; it must be infinite

– If we ought to obey that law then that infinite law-giver must be personal

– If we ‘ought’ to do something, we must be obligated to do it, and we cannot be obligated to something impersonal, only something personal. - So the fact that there are certain things that are objectively morally wrong, and we ought not to do them, means that there must be a personal, infinite moral law-giver

- That is, there must be a God

Now, whatever we think of the conclusiveness of that moral argument for God, we can use it as a tool to see what will happen if we turn it round the other way. If we work back up the argument from Dawkins’ supposed non-existence of God we will see whether an atheist like Dawkins can logically also believe in the existence of a real right and wrong, let alone the concept of anything being evil.

According to Dawkins, we evolved solely through survival of the fittest. Therefore, there can be no-one to obligate us such that we really ought not to do something. Of course, we might have evolved in such a way that we don’t do something, or we might live in a society in which other people have evolved such that they try to force us not to do something. But that is simply the result of blind, purposeless evolution. We cannot really be obligated not to do it. In an atheistic evolutionary world, things just are the way that they are. If there was no purpose in our evolution, there can be no concept of the way things ‘ought to be’.

What is more, if our evolution took place through the natural selection of random mutations, then there can be no objective source of right and wrong. We can talk about how things are for some people, and we can compare that with how they are for other people. We can even talk about how things make us better fitted for survival. But we can never talk about whether things are objectively morally right or wrong. If there was no design behind our evolution then there can be no objective template against which to judge any absolute right and wrong.

So, how can Dawkins talk about anything being evil? Surely, even any use of that term contradicts his belief about reality.

But, Dawkins self-contradiction doesn’t stop there. In The Root of all Evil? he repeated his regular call for people to test their beliefs by using the scientific method. He called upon people only to believe something if there was scientific evidence for it. By scientific evidence he means some form of experiment that enables us to test the belief in some empirical way. Boiled down to its basic form, Dawkins says, ‘only believe something if there is scientific evidence that it is true.’ Unfortunately, yet again Dawkins falls into the fallacy of self-contradiction. When telling us, ‘only to believe something if there is scientific evidence that it is true,’ he is telling us to believe something (that we should only believe something if there is scientific evidence that it is true). Now, we might reasonably ask him to tell us what scientific evidence he can give us for this belief. By his own argument, there should be scientific evidence for the truth of the statement that we should ‘only believe something if there is scientific evidence that it is true.’ Of course he can’t give us any. That statement is not verifiable scientifically. It is an expression of his belief. It is a statement of his faith.

Dawkins is not the only one to have succumbed to this particular self-contradiction. In the last century there was a group of people who fell into this trap. They called themselves the Vienna Circle. They were a number of people who met in Vienna University in the 1920s and 1930s, mainly under the instigation of Moritz Schlick. They gave birth to the philosophy known as Logical Positivism with its central belief in the Verification Principle. This principle argued that no statement is meaningful if it cannot be verified empirically.[3]

Of course, since then many philosophers have recognized that their statement of the Verification Principle was self-contradictory since the principle itself cannot be verified empirically. But that did not stop them from using the principle to launch attacks on religious beliefs.

It is remarkable that, today, while the most basic dictionaries of philosophy highlight the problems with logical positivism, Dawkins receives so much air-time to trot out the same criticism of religious belief, based on a discredited argument.

Programme title: The Root of all Evil?

Presenter: Richard Dawkins

Broadcaster: Channel 4

First broadcast: 9 January 2006 (Part 1), 16 January 2006 (Part 2)

Go to Part 2

[1] The Root of All Evil, Channel 4, 9 January 2006.

[2] A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning that renders an argument invalid. For a large list of fallacies see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fallacy. For an article alleging 11 logical fallacies of Dawkins see http://www.arn.org/docs/williams/pw_dawkinsfallacies.htm.

[3] Strictly speaking the Verification Principle asserts that a statement can be meaningful, even if it is not empirically verifiable, if it is an analytic rather than a synthetic statement. An analytic statement is one in which the concept of the predicate is included in the concept of the subject. Thus ‘all bachelors are unmarried men’ is an analytic statement – since bachelors are, by definition, unmarried men (and unmarried men are, by definition, bachelors). Therefore the Logical Positivists would say that this does not need empirical verification since it is verified analytically. On the other hand a synthetic statement is one which gives new information – such as ‘This bachelor has brown hair’ – and, according to Logical Positivism, is only meaningful if it is empirically verifiable. But Dawkins’ statement is not an analytic statement, it is a synthetic statement. Therefore, according to Logical Positivism, it is only meaningful if it is empirically verifiable.

Related articles/study guides:

© 2005 Nick Pollard