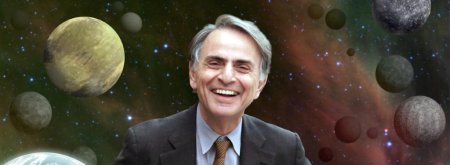

Carl Sagan: The Skeptic's Sceptic

In 1985, Carl Sagan, better know for his book and television series Cosmos, delivered the Gifford Lectures. The transcripts were only recently published as The Varieties of Scientific Experience: a personal view of the search for God (Penguin, 2006). Peter S. Williams has written an extended review of the book. His review provides some excellent responses to arguments that Sagan uses and which keep cropping up today.

Part 4: Religious Experience

Having comprehensively failed to show that natural theology is a lost cause (cf. Part 3), Sagan ends his Gifford Lectures by turning the spotlight upon religion as a sociological phenomenon with its roots in our evolutionary psychology.

Sagan does avoid the ‘genetic fallacy’ of thinking that providing a plausible account of the origins of religion in some way undermines the truth-claims of religion. A naturalistic account of religion is compatible with the religious viewpoint. It is only a metaphysically naturalistic account of religion that stands in contradiction to the religious viewpoint; and the metaphysical status of a naturalistic account of religion cannot be determined with reference to the account in isolation. For example, if a propensity to believe in the Transcendent is built into humanity by our evolutionary history – is that history ‘nothing but’ a matter of contingent happenstance, or is it in some way teleologically related to the Transcendent? Simply from looking at the historical process, one cannot rule out an underlying intent. Hence Sagan proceeds on the metaphysical assumption that religion is a false viewpoint in need of understanding and explanation. But as Parts 1-3 of this review indicate, I do not think we are under any compulsion to grant Sagan this assumption.

The origins of religion

Nor are we under any compulsion to accept that Sagan’s account of the origins of religion is true. As Sagan admits:

‘Clearly there are no observers in our time who were present hundreds of thousands of years ago, and there can be no confident assertions on this subject. All we can have is differing degrees of plausibility.’ (p. 174)

The thing is, Sagan’s historical account isn’t particularly plausible. For example, he observes of ancient humanity that:

‘Whatever our feelings and thoughts and approaches to the world were then, they must have been selectively advantageous, because we have done rather well.’ (p. 170)

But this evinces a simplistic understanding of evolution, for in evolutionary theory not every surviving trait does have to be advantageous. Rather, every surviving trait has to be not sufficiently disadvantageous so as to prevent reproduction. Natural selection weeds out what doesn’t work, thereby promoting the best available composite of features. But if a feature that is disadvantageous when considered in isolation is somehow linked to a feature of great advantage, then the disadvantageous feature may be propagated on the back of the advantageous feature.

Whether the evolution be biological or sociological, it is all too easy to concoct a simplistic ‘just-so’ story that beautifully fits one’s pre-conceived conclusions and the limited evidence available to us, and which moves surreptitiously in the mind of story-teller and listener alike from the realm of ‘could be true’ to the realm of ‘established scientific fact’. For example, Sagan describes how adrenaline triggers:

‘the flight-or-fight syndrome. This molecule makes you either aggressive or, if you want to think about running away, cowardly, one or the other. Very remarkable that two such apparently contradictory emotions can be brought about by the same molecule.’ (pp. 181-182)

He proceeds to spin a ‘just-so’ story:

‘Consider our remote ancestors faced with… hyenas, not yet having deduced that hyenas with fangs bared are dangerous. It would be too inefficient to have our ancestor consciously stop and think, "Oh, I see those beasts have sharp teeth; they probably can eat somebody. They’re coming at me. Maybe I should run away." By then it’s too late. What you need is a quick look at the hyena, and instantly the molecule is produced, and you run away, and later you can figure out what happened. And you can see two populations, one of whom has to slowly think the matter out the other of whom can rapidly respond to the adrenaline. After a while these guys [the reactors] leave lots of offspring, those guys [the thinkers] don’t. Everybody winds up generating adrenaline. Natural selection. Not hard to understand how it comes about.’ (p. 182)

Note, first of all, that this is not actually an explanation of the origin of adrenaline and / or the flight-or-fight response, but rather an explanation of its presumed shift from low to universal incidence in a population. But how long, exactly, does it take to deduce that hyenas (etc.) might be dangerous and that running away might be a good idea? Why must our would-be ancestors think the matter our ‘slowly’, rather than with alacrity? Even if hyena-wary conclusions are not reached a priori (quickly or otherwise), one narrowly survived fight with a hyena, a single observed instance of someone else failing to best a hyena, and one would have thought that the message might hit home efficiently enough. One might even think that word of this conclusion (literal or figurative) might spread to those without any hyena experiences of their own. Mightn’t even a fairly slow thoughtful approach to problem solving constitute an over-all survival advantage as compared to molecular-based responses, even if it were a disadvantage in certain hyena intensive situations? Couldn’t the same hyena story just as easily be used to ‘explain’ how the knack of quick-thinking spread from a few ancestors lucky enough to be good at it to the ancestral population as a whole? But if the same story can be used to ‘explain’ such apparently contradictory facets of human nature as deductive reason and instinctive reaction, can it really be said to explain either? And, since Sagan notes that the very same molecule can trigger not only the urge to flee, but also the urge to stand and fight, why is it that our hypothetical ancestors in Sagan’s story all flee and survive to pass on their adrenaline-producing genes, rather than heroically but uselessly standing up to the hyenas and their bared teeth, thereby removing themselves from the gene-pool? Sagan’s story stacks the deck in its own favour. Perhaps the real explanation is more complicated.

If the real explanation is likely to be more complex, Sagan’s story can’t be treated as more than the merest sketch of a speculation about how things might have happened. Building any scientific or metaphysical hypothesis upon such a ‘just-so’ story would amount to erecting a house of cards. Nor, given the sketchy nature of such a ‘just-so’ story, can it simply be assumed that the real explanation doesn’t contradict any of the assumptions – scientific or metaphysical – that this ‘just-so’ story was shaped to fit. More to the point, Sagan’s explanation for the origin or religion has exactly this ‘just-so’ nature, and so it would be wise neither to put too much stock in his explanation, nor to build metaphysical houses upon it.

Sagan follows previous Gifford Lecturer James Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1912) in suggesting that religion began with a belief in animism and an attempt to gain control over nature by showing reverence to the forces thought to control it:

‘One thing we do if we believe that there is a god of the thunderbolt and do not wish to be hit by a thunderbolt is to propitiate the god of the thunderbolt, to do something to calm him down… to show our respect for him… And many cultures have such institutionalised propitiation, which sometimes goes as far as human sacrifice…’ (pp. 174-175)

Of course Sagan is right up to a point; but if this story is meant to explain the origin of religion per se then we need (a) some account of why people believe in animism in the first place, and (b) some account of why people don’t stop being religious when they notice (as they must notice) that propitiating the god of thunder does not necessarily ‘calm him down.’ If control over nature is the goal of religion, and religion is false and so delivers only ‘the illusion that by some sequence of ritual actions we are able to influence forces of nature’ (p. 175), then why does religion persist? Why didn’t ancient humanity all go the way of the Greek materialists, or at least figure that the gods pay humans no attention and have no favourites?

As Alister McGrath notes: ‘The evidence simply isn’t there to allow us to speak about any kind of "natural progression" from polytheism to monotheism… The rise of modern anthropology can be seen as a direct reaction to the manifest failures of Frazer’s The Golden Bough [which] totally lacked any serious basis in systematic empirical study’[104]. In point of fact, there is good reason to believe that religion did not begin with animism and ‘evolve’ from there towards monotheism, as Frazer hypothesised. Quite the reverse. Norman L. Geisler comments:

‘Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1912) has dominated the history of religion for the past few generations. His hypothesis is that religions evolved from animism through polytheism to henotheism and finally monotheism. In spite of its selective and anecdotal use of sources that are outdated by subsequent research, the ideas from the book are still widely believed… There are many arguments in favor of primitive monotheism. Many come from the records and traditions we have of early civilization. These include Genesis, Job, the Ebla Tablets, and the study of preliterate tribes… The origins of polytheism can be explained as well, if not better, as a degeneration from original monotheism… This is evident in the fact that most pre-literate religions have a latent monotheism in their view of the Sky God or High God… there is every evidence to believe that monotheism was the first religion from which others Devolved…’ [105]

As G.K. Chesterton argued in 1925:

‘They are obsessed by their evolutionary monomania that every great thing grows from a seed, or something smaller than itself. They seem to forget that every seed comes from a tree, or from something larger than itself. Now there is very good ground for guessing that religion did not originally come from some detail that was forgotten because it was too small to be traced. Much more probably it was an idea that was abandoned because it was too large to be managed. There is very good reason to suppose that many people did begin with the simple but overwhelming idea of one God who governs all; and afterwards fell away into such things as demon-worship… Some of the very rudest [i.e. primitive] savages [i.e. un-industrialised indigenous peoples], primitive in every sense in which anthropologists use the word, the Australian aborigines for instance, are found to have a pure monotheism with a high moral tone… He is worshiped by the simplest tribes with no trace of ghosts or grave-offerings, or any of the complications in which Herbert Spenser or Grant Allen sought the origin of the simplest of all ideas. Whatever else there was, there was never any such thing as the Evolution of the Idea of God. The idea was concealed, was avoided, was almost forgotten, was even explained away; but it was never evolved.’ [106]

Chesterton pointed to the God-implying shadow of the divine absence that hangs over ancient pagan philosophy and religion:

‘The best authorities seem to think that though Confucianism is in one sense agnosticism, it does not directly contradict the old theism, precisely because it has become a rather vague theism. It is one in which God is called Heaven, as in the case of polite persons tempted to swear in drawing-rooms. But Heaven is still overheard, even if it is very far overheard. We have all the impression of a simple truth that has receded, until it was remote without ceasing to be true. And this phrase alone would bring us back to the same idea even in the pagan mythology of the West. There is surely something of this very notion of the withdrawal of some higher power in all those mysterious and very imaginative myths about the separation of earth and sky. In a hundred forms we are told that heaven and earth were once lovers, or were once at one, when some upstart thing, often some undutiful child, thrust them apart; and the world was built on an abyss; upon a division and a parting… mythology grows more and more complicated, and the very complication suggests that at the beginning it was more simple… there is therefore a very good case for the suggestion that man began with monotheism before it developed or degenerated into polytheism.’ [107]

Perhaps one is tempted to say, in response to Chesterton, that he is simply spinning a plausible story to fit a minimal amount of hard evidence (or an interpretation thereof). Personally, I find Chesterton’s story far more plausible than Sagan’s; but if Chesterton’s story is speculative, then so too is Sagan’s.

Sagan equates Jewish and Christian beliefs about sacrifice with animistic beliefs about the course of nature being ‘different from what it otherwise would be. It provides the illusion that by some sequence of ritual actions we are able to influence forces of nature’ (p. 175). But of course, Judeo-Christian beliefs about sacrifice have nothing to do with influencing the course of nature, and everything to do with altering human standing in relation to concepts such as moral wrong (sin) and forgiveness. And far from sacrifice being a human ruse to influence God, in the Judeo-Christian tradition one might very well say that the sacrifice (whether a goat or Jesus himself) is a divine ruse to influence humans!

On the assumption that contemporary so-called ‘primitive’ cultures will give insight into ‘primitive’ cultures of the distant past, Sagan compares the !Kung of the Kalahari Desert with the Jivaro of the Amazon Valley. It is worth pausing to question Sagan’s assumption with Chesterton:

‘Of course most of these speculators who are talking about primitive men are thinking about modern savages. They prove their progressive evolution by assuming that a great part of the human race has not progressed or evolved; or even changed in any way at all… Modern savages cannot be exactly like primitive man, because they are not primitive. Modern savages are not ancient because they are modern. Something has happened to their races as much as to ours, during the thousands of years of our existence and endurance on the earth. They have had some experiences, and have presumably acted on them… They have had some environment, and even some change of environment, and have presumably adapted themselves to it in a proper and decorous evolutionary manner.’ [108]

The !Kung are described by Sagan in glowing terms. There is a sexual division of labour, but little social hierarchy. Children are loved and warfare rare. There is the encouragement of religious experiences through the use of hallucinogens. The Jivaro, on the other hand, torture their enemies, brutalize their children, and drink alcohol. And they believe in a Supreme Creator God. Sagan hammers home the point with reference to a statistical correlation taken from the work of neuropsychologist James Prescott [109] (a member of the Board of Directors of the American Humanist Association):

‘the things that apparently go with each other are essentially the two sets of characteristics I just described. It is Prescott’s view that there are causal relations. That, in fact, in his view the key distinction has to do with whether cultures hug their children and whether they permit premarital sexual activity among adolescents. In his view these are the keys. And he concludes that all cultures in which the children are hugged and the teenagers can have sex wind up without powerful social hierarchies and everybody’s happy. And those cultures in which the children are not permitted to be hugged… and a premarital adolescent sexual taboo is strictly enforced wind up killing, hating, and having powerful dominance hierarchies.’ (p. 173)

These two sets of comments are apt to lead the unwary reader to conclude that societies that believe in a Supreme Creator God are bad and that societies which don’t are good. Sagan denies that this is his intent:

‘Now, you cannot prove a causal sequence from a statistical correlation. And you could just as well argue that what the religious forms are determines everything or what the sacrament is has a powerful connection, between societies with alcohol and the societies that torture their enemies and abuse women and so on.’ (p. 173)

Besides, what would such a theory make of Christianity, which believes in a Supreme Creator God, uses alcohol as a sacrament and makes extra-marital sex taboo, but which ‘says not just abide your enemy, not just tolerate him, love him… No ifs, ands, or buts’ (pp. 208-209), which says to love children, and which greatly elevates the place of women compared to the way of things in the ancient world?

Prescott’s study has been criticised for biased data collection and inadequate statistical analysis[110], so it is fortunate – if somewhat bemusing – that all Sagan claims on the back of anthropological studies is that:

‘there are two and probably a multiplicity of ways of being human. That these cultures… must be within us… that is, a hardwired circuit in our brains that permits us to fit… into some dominance hierarchy… And at the same time, we must also have some predisposition for the antithesis…’ (pp. 173-174)

Indeed. But there is no either / or here. After all, Christianity sets up a strict hierarchical relationship between God and humanity, on the basis of which it proclaims that all people are equally made ‘in the image of God’ (Genesis 1:27), and that for believers: ‘There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus’ (Galatians 3:28).

Prayer – what is it good for?

Sagan recounts Francis Galton’s (somewhat tendentious) attempts to place the study of prayer on a scientific footing, which he laments: ‘has not led to a school of people who do statistical tests of the efficacy of prayer’ (p. 177). Once again, the intervening years have seen interesting developments in the sort of research that Sagan calls for. Of course, Sagan is correct when he notes that:

‘There is no question that there is something about prayer that seems to work. Surely it provides solace and comfort. It’s a way of working through problems. It’s a way of reviewing events that have happened, of connecting the past to the future. It does some good.’ (p. 177)

But Sagan opines that this: ‘doesn’t say anything about the existence of a god. It doesn’t say anything about the external world. It is a procedure, which on some level makes us feel better’ (p. 177). I don’t accept Sagan’s assumptions that such prayer as he thinks useful is nothing but a procedure that works, or that prayer can only have something to say about the existence of God if it makes a difference to the external rather than the internal world. But rather than arguing the toss, let’s join Galton’s game of statistical investigation into what is rather blasphemously called ‘the efficacy of prayer’.

A systematic review of the efficacy of distant healing published in 2000 concluded that: ‘approximately 57% (13 of 23) of the randomised, placebo-controlled trials of distant healing... showed a positive treatment effect’[111]. Moreover:

‘David R. Hodge, an assistant professor of social work in the College of Human Services at Arizona State University, conducted a comprehensive analysis of 17 major studies on the effects of intercessory prayer… among people with psychological or medical problems. He found a positive effect.’ [112]

Hodge’s meta-analysis was featured in the March 2007 issue of Research on Social Work Practice. According to Hodge:

‘This is the most thorough and all-inclusive study of its kind on this controversial subject that I am aware of… It suggests that more research on the topic may be warranted, and that praying for people with psychological or medical problems may help them recover… Overall, the meta-analysis indicates that prayer is effective.’ [113]

For example:

• Dr [Randolf] Byrd divided 393 heart patients into two groups. One was prayed for by Christians; the other did not receive prayers from study participants. Patients didn’t know which group they belonged to. The members of the group that was prayed for experienced fewer complications, fewer cases of pneumonia, fewer cardiac arrests, less congestive heart failure and needed fewer antibiotics. [114]

• Dr Dale Matthews documents how volunteers prayed for selected patients with rheumatoid arthritis: ‘To avoid a possible placebo effect from knowing they were being prayed for, the patients were not told which ones were subjects of the test. The recovery rate among those prayed for was measurably higher than among a control group, for which prayers were not offered.’ [115]

So there is at least some scientific evidence for the efficacy of prayer in the external world. Given Sagan’s sceptical approach to miracles (which he inaccurately compares to the request that twice two not equal four) it is interesting that he even calls for the research, now carried out, the results of which stand in prima facie tension with his naturalistic assumptions.

The historical Jesus

Sagan inaccurately asserts that: ‘The only evidence for the existence of Jesus is the four Gospels and the subsequent books. And apart from that, there is merely the account of Josephus’ (p. 237). This is not true[116]; but even if it were, the evidence Sagan accepts is more than sufficient. Sagan admits: ‘I find the accounts in the Gospels reasonably internally consistent, and I don’t see any particular problem about Jesus as a historical figure in the same sense as Mohammed and Moses and Buddha’ (p. 237). However, Sagan is not willing to take the historical evidence concerning Jesus, Mohammed, Moses or Buddha at face value, saying: ‘I think the less unsatisfactory hypothesis is that they were real people, genuine historical figures, great men, the details of whose lives and missions have been, of course, distorted by subsequent advocates and enemies both’ (p. 237). No argument for the unreliability of our data on Jesus is offered, but one can see why someone who thinks that ‘The definitive work on miracles was written by… David Hume’ (p. 136) might ride roughshod over the historical evidence here – for that is exactly what Sagan is doing.

Religion has its uses

Sagan is to be commended for avoiding the partisan, religion-phobic rhetoric of the New Atheism. He is actually keen to emphasise various positive aspects of religion for society:

‘It seems to me that there are many respects in which religion can play a benign, useful, salutary, practical, functional role in the prevention of nuclear war… religious people played a role in the abolition of slavery in the United States, and elsewhere. Religions played a fundamental role in the independence movement in India and in other countries and in the civil rights movement in the United States. Religions and religious leaders have played very important roles in getting the human species out of situations that we should never have gotten into that profoundly compromised our ability to survive, and there is no reason religions could not in the future take on similar roles… Religions, because they are institutionalized and have many adherents, are able to provide role models, to demonstrate that acts of conscience are creditable, are respectable… Religions can combat fatalism. They can engender hope. They can clarify our bond with other human beings all over the planet. They can remind us that we are all in this together.’ (pp. 205-207)

Sagan highlights Jesus’ unique elucidation of the Golden Rule: ‘it’s that strong statement of the Golden Rule that sets Christianity apart’ (p. 209).

However, because Sagan rejects the truth of all religious viewpoints (excepting his own secular humanism), he judges religion against the criterion of pragmatic usefulness. Indeed, Sagan is overwhelmingly concerned with species survival, and whether or not religion detracts from or contributes to such survival. He thinks, on balance, that it probably contributes. Whether or not he is right about this, there is something wrong with his survival criterion; for in discussing the question of purpose Sagan, having rejected the existence of a purposer of life, naturally rejects any given purpose given to life:

‘I would say that purpose is not imposed from the outside; it is generated from the inside. We make our purpose. And there is a kind of dereliction of duty of us humans when we say that the purpose is to be imposed on the outside…’ (p. 227)

This existentialism is self-contradictory. If there is no objective purpose, then we cannot be guilty of any ‘dereliction’ of that purpose in saying that there is an objective purpose given to existence from ‘the outside’! Moreover, any subjective purpose we invent remains our own invented, subjective purpose that is quite likely to be at cross-purposes with the subjective purposes of others. We may, like Sagan, embrace the subjective purpose of having the human species survive – but such a personal choice is forever doomed to remain on entirely equal terms with the personal choice to push the big red destruct button on humanity. Sagan thinks that:

‘Extinction undoes the human enterprise. Extinction makes pointless the activities of all our ancestors back those hundreds of thousands or millions of years.’ (p. 204)

But in that case, unless he thinks humanity is going to live literally forever in the cosmos despite the fact that ‘Most species become extinct’ (p. 204), Sagan’s own views entail the conclusion that life is pointless at present!

Sagan clearly wants to say that the human struggle is not pointless at present, and that we have an actual duty not to destroy the earth in nuclear war - ‘we have many obligations to guarantee our purposes, one of which is to survive’ (p. 227) – but he rejects the metaphysical apparatus necessary to making such a claim coherent. That metaphysical apparatus is of course belief in the existence of a Personal Transcendent Creator, i.e. ‘God’.

On the other hand, the metaphysical view that makes a belief in objective ‘purpose’ and ‘duty’ coherent (such as a purpose that excludes the extinction of humanity and a duty not to destroy ourselves) is also the view that demotes survival from the position of supreme importance it occupies in Sagan’s ethic. For Sagan thinks that if past generations have struggled for anything, ‘it was the survival of our species’ (p. 204). Yet it seems to me that very few people have historically been concerned with the survival of our species. They have been concerned with all sorts of other things, including eternal things that Sagan’s worldview excludes from consideration. Besides which, if the moral argument is correct (cf. Part 3), Sagan is unable to justify attaching any objective moral value to the idol of ‘survival’. Sagan thinks that: ‘the preservation of life is essential if religion is to continue. Or anything else’ (p. 205). But of course, if Christianity is true, Sagan is wrong about this for the simple reason that the cosmos is not all there ever was, nor all there is, nor all there ever will be.

Sagan’s critical musings about religion range from the implausible (e.g. that animism preceded monotheism), to the self-contradictory (e.g. that life is without purpose but that we have an objective duty to create our own purpose).

Concluding Remarks

As I bring this review to a close, my general impression is that Sagan’s Gifford Lectures display a far-ranging ignorance of serious philosophical and theological scholarship. Sagan is often guilty of attacking a ‘straw-man’ and makes several arguments that are logically invalid (which beg-the-question or even contradict themselves), but even when his logic is valid, his crucial premises are less plausible (sometimes far less plausible) than their denials.

The over two decade gap between Sagan’s lectures and their publication provides a fascinating glimpse into the way in which the march of scientific discovery has actually added weight to the case for a theistic worldview. As we have seen, whether one considers the fields of cosmology, astrobiology, or studies into the efficacy of prayer, science has in each case produced results that are uncomfortable for adherents of a naturalistic worldview.

Reading Sagan does at least provide a welcome break from the acerbic rhetoric of the ‘New Atheism’. Whether or not he always succeeds (and which of us does), Sagan obviously attempts to be fair-minded in his exploration of the interface between science and religion, and for this he should be praised. So allow me to end with a quote from Sagan with which I am in wholehearted agreement:

‘I would suggest that science is, at least in part, informed worship. My deeply held belief is that if a god of anything like the traditional sort exists, then our curiosity and intelligence are provided by such a god. We would be unappreciative of those gifts if we suppressed our passion to explore the universe and ourselves.’ (p. 31)

Go back to Part 1: Introduction

References

[104] Alister McGrath, The Dawkins Delusion, (SPCK, 2007), pp. 31 & 33.

[105] Norman L. Geisler, ‘Primitive Monotheism’ @ www.ses.edu/Portals/0/journal/articles/1.1Geisler.pdf.

[106] G.K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man, (Hodder & Stoughton, 1927), pp. 101 & 103.

[107] ibid, pp. 104-106.

[108] ibid, pp. 63-64.

[109] cf. James Prescott, ‘Body Pleasure and the Origins of Violence’ @ www.violence.de/prescott/bulletin/article.html.

[110] cf. www.kuro5hin.org/comments/2003/4/23/182233/949/210#210.

[111] J.A. Astin, E. Harkness & E. Ernst MD, ‘The efficacy of "distant healing": a systematic review of randomized trials’, Ann Intern Med 2000;132:903-10.

[112] ‘Does God Answer Prayer? ASU Research Says "Yes"’ @ www.physorg.com/news93105311.html.

[113] David R. Hodge quoted by ‘Does God Answer Prayer? ASU Research Says "Yes"’ @ www.physorg.com/news93105311.html.

[114] Phyllis McIntosh, ‘Faith is Powerful Medicine’, Reader’s Digest, May, 2000. cf. R.C. Byrd, ‘Positive Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer in a Coronary Care Unit Population’, Southern Medical Journal 81:826-829.

[115] Charles Colson & Nancy Pearcy, How Now Shall We Live?,(Tyndale House, 1999), p. 313.

[116] cf. Gary R. Habermas, ‘Ancient Non-Christian Sources’ @ www.garyhabermas.com/book/historicaljesus/historicaljesus.htm#ch9.

© 2008 Peter S. Williams

Go back to Part 1: Introduction