The Resurrection of Jesus and the Witness of Paul

In March 2008, Professor Gary Habermas, Distinguished Research Professor and Chair of the Philosophy and Theology Department at Liberty University, Virginia, USA toured Britain to speak about his specialist subject, the historical evidence for the resurrection.[1] Dr Peter May accompanied the tour and reviews here the main lines of his argument.

Nearly 40 years ago, C.H. Dodd put forward the idea that St Paul’s credal statement in 1 Corinthians 15 could be confidently traced back to Jerusalem in around AD 35.[2] This idea has captured the mind of New Testament scholarship to such an extent that few scholars today doubt it. It was an idea of immense significance. Dodd wrote, “We have here a solid body of evidence from a date close to the events,” and according to Gary Habermas, it has changed the thinking of an entire generation of scholars.[3] The argument hangs on two reliable texts.

The Creed

The overwhelming consensus of scholarship today accepts that the apostle Paul wrote the New Testament letters 1 Corinthians and Galatians, and that we have a very reliable account of what he actually wrote. In 1 Corinthians 15, Paul starts the chapter by saying that he wants to remind them and make clear for them the gospel he had preached to them and on which they had taken their stand. He then states that he had delivered to them what he had also received (verse 3). These verbs are the equivalent Greek words for the technical rabbinic terms, which were used to describe the handing on of a formal, word of mouth, memorised, formulaic teaching. This is what he had delivered to them and he said it was a matter “of first importance”. He then recites the credal statement, which is usually said to consist of two parallel sentences structured rhythmically as an aide memoire. It reads:

Christ died / for our sins / according to the scriptures / and was buried

He was raised / on the third day / according to the scriptures / and appeared

To Peter / and to the twelve.

(1 Corinthians 15:3-5)

Dating the Creed

Christ’s death is generally thought to have occurred in AD 30 (or 33).[4] Paul wrote his letter to the church at Corinth around AD 55, some 25 years later. He had delivered this creed to them when he visited Corinth in AD 51. Few dates could be more certain, because while he was there he was hauled up before the Roman proconsul Gallio (Acts 18:12-17). Gallio, who subsequently conspired against Nero, was the brother of the philosopher Seneca. Proconsulship was a one year post and a Roman stone inscription found early in the 20th century at nearby Delphi records his period of office as being AD 51-52. This date is so firmly established that it has become one of the lynchpins for working out the dates of the rest of New Testament chronology.

Following this credal formula, Paul also lists other resurrection appearances (1 Corinthians 15:6-8):

Then he appeared to more than 500 hundred brothers at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles. Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me.

It is uncertain whether some of this was part of the original credal formula, a different formula or added commentary from Paul. For instance, his statements “most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep”, and his final sentence about himself appear to be Paul’s additional comments.

Peter, Paul and James

Interestingly, besides himself, Paul only names two other individuals in this list, the apostle Peter and James. James, who was the Lord’s brother, became the head of the church in Jerusalem (Acts 12:17, 15:13, 21:18).[5] He is not to be confused with James, the brother of John, who had already been put to death by Herod, in about AD 44 (Acts 12:2).

The appearances to these three individuals were particularly poignant. Prior to the crucifixion, Peter had denied that he even knew Christ (Mark 14:66-72). James had not believed in his own brother (Mark 3:21; 6:3-4; John 7:5). Paul had been a leading activist in the persecution of the church (Acts 8:3, 1 Corinthians 15:9). Their experiences of the risen Christ not only radically changed the direction of their lives but ultimately led to their martyrdom.[6]

According to Paul’s letter to the Galatians, it was these three key figures who met together in Jerusalem, three years after Paul’s Damascus road experience (Galatians 1:18-19). Paul states that he went to Jerusalem to visit Cephas (Peter), but the verb he used was “historeo”, which means not just to visit but to investigate or research matters.[7] Furthermore he stayed with him for 15 days (Galatians 1:18). He says that he saw none of the other apostles at that time, except James the Lord’s brother (verse 19). So when Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 15 that the risen Christ appeared individually to both Peter and James, he was effectively saying “I know this because I have heard their story first hand”.

The context of his report in Galatians concerns the content of the Gospel. The Galatians had been embracing “a different gospel” because some had been “distorting the gospel” (Galatians 1:6-7). So Paul didn’t visit Jerusalem to discuss trivialities. In clarifying the gospel which they were preaching, it is overwhelmingly probable that Paul received this authoritative oral creed with its list of witnesses from Peter and James, if he had not already learned it from Christians in Damascus.

We do not know when Paul was converted, but it was clearly early in the life of the infant church. Some scholars think it was within a year of the crucifixion. Most think it was around two years after Christ’s death. This would mean that this ‘summit conference’ between Peter, James and Paul occurred three years later, i.e. by AD 35. However, the phrase “after three years” (Galatians 1:18), could equally well mean “in the third year”, which could mean they met only 18 months after his conversion. (A similar phrasing is used of Christ being raised “after three days” (Matthew 27:63, Mark 8:31) or “on the third day” (1 Corinthians 15:4) when in fact he was crucified late on Friday and the empty tomb was discovered early on Sunday, that is just 36 hours later.) So the credal statement would have been received by Paul within five years of Christ’s death and possibly within only two or three years.

All of One Mind

A major implication of all this is that these three key leaders were all in agreement about the central content of the gospel at this very early stage.

Paul however goes on to say that he revisited Jerusalem “after fourteen years” (Galatians 2:1). (It is usually assumed this is counted from the date of his Damascus road conversion but he may have meant after the initial meeting in Jerusalem.) He returned explicitly to “set before them the gospel I proclaim among the Gentiles, in order to make sure I was not running in vain” (Galatians 2:2). He took with him Barnabas and Titus and they met Peter and James, but now also the apostle John (Galatians 2:9). This was an extraordinary group of the most prominent members of the apostolic team – Peter, James, John, Paul plus Barnabas and Titus. Paul says of these men, concerning the gospel he preached, that they “added nothing to me” (Galatians 2:6) and went on to say in verse 9 that, “James, Peter and John, who seemed to be pillars … gave the right hand of fellowship to Barnabas and me, that we should go to the Gentiles and they to the circumcised” (i.e. the Jews).

It is these statements that lie behind Paul’s emphatic claim in 1 Corinthians 15, which follows the credal statement with its list of witnesses, including “all the apostles” (verse 7). Paul wrote, “Whether then it was I or they, so we preach and so you believed” (1 Corinthians 15:11). They were all ‘on the same page’.

Statements under Oath

So how do we know these things are true? Well, we have the apostle Paul’s clear statements that this is what happened. But such is the importance of these things, that he puts himself on oath for what he reported about that first crucial meeting. “I assure you before God that what I am writing is no lie” (Galatians 1:20).

Furthermore he makes a rather similar statement after the list of resurrection witnesses: “If Christ has not been raised, we are even found to be false witnesses concerning God, because we gave testimony against God that he raised Christ, whom he did not raise” (1 Corinthians 15:15).

Before AD 35

If this fixed oral formula was passed on to Paul by AD 35, it must have already been in existence. Prior to that, the apostles must have believed these things to be true. Prior to their beliefs, were the experiences that led them to believe that Christ had risen. Behind them lay the historic facts of Christ’s death and empty tomb.

Consequently, a number of critical scholars are concluding that the belief in Jesus as crucified Messiah and risen Lord was central to the united apostolic proclamation of the apostles before Paul’s conversion, and at no stage was Jesus proclaimed in lesser terms.

On this basis, the idea that Paul invented Christianity crashes. So does the idea that ‘resurrection’ was a late addition to Christian thinking. Furthermore, the view that Christ was only gradually recognised as being divine also falls.

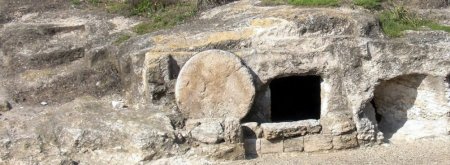

But Was the Tomb Empty?

It has been supposed that Paul’s Damascus road experience was essentially different from the experience of the other apostles. His experience has been held to be mystical and subjective, while theirs was physical and objective. Furthermore, it is argued, Paul says nothing about the tomb being empty.

Paul, however, does not differentiate his experience from the rest of the apostles, other than in its timing. He was not with them at the beginning. He says “he appeared to Peter … he appeared to James … and last of all he appeared also to me”. Previously he had asked. “Am I not an apostle? Have I not seen Jesus our Lord?” (1 Corinthians 9:1). He says nothing to imply that his experience was essentially different from theirs.

While he does not refer to the tomb being empty, it is implicit in the creed. Firstly, the creed describes the progression “died … buried … raised … appeared”. Whilst modern people might be tempted to separate these meanings, a first century Jew would only have believed that the sentence implied a continuity. What was dead was buried, what was dead and buried was raised, and what was dead, buried and raised also appeared. The clear implication of this creed is that Jesus underwent a bodily resurrection.

Secondly, the creed is emphatic that something happened “on the third day”. That event, we are told, is that Jesus “was raised”. The appearances, which followed, continued over several weeks.

Thirdly, we need to imagine how Paul and Peter spent their time when they spent 15 days together in Jerusalem. We have already noted that Paul went there “to investigate”. Did they not retrace Christ’s final journey? Did they not pause for prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane or stand where the cross had stood? Did Peter not show him the tomb where he and John had discovered the grave clothes? This, of course, is speculation. But Paul wanted to clarify the facts – and 15 days in a small city is a long time.[8] There are therefore very good reasons to believe that Paul was fully aware that the tomb was empty.

Should we Believe Their Witness?

It is often claimed that because these things happened so long ago, they are intrinsically unreliable due to the passing of so many years. However, once the eyewitnesses have died, their written testimony does not become less credible with the passing of time. The important questions are whether the testimony is early, whether it is from eyewitnesses, whether the individuals are being honest and whether the text is reliable.

Compare for instance comparable works from antiquity. The great Roman historian Tacitus, in his Annals of Imperial Rome, recorded events from the death of Augustus in AD 14 to the death of Nero in AD 68. Yet Tacitus was not born until AD 55 and did not write the Annals until around AD 110. In other words, he wrote up to 100 years after events he described. Furthermore, there are only two ancient manuscripts which have survived. The older manuscript was written about AD 800!

Livy wrote 142 books on Roman history during the reign of Augustus; 35 of these books have survived. His writings covered a period from the foundation of Rome in 753 BC to his own lifetime. The oldest surviving manuscript dates from the 4th century AD.

In contrast, there are over 5000 ancient manuscripts of the New Testament in Greek, and many more in other languages – a vast, dispersed library from which to establish the original text. The oldest manuscript of Paul’s letters, known as Papyrus 46 is held in the Chester Beatty collection in Dublin. The handwriting is the main clue to its date. It is believed to have been written in Egypt around AD 200, only 150 years after the original.

For the central truths of the gospel, then, we have very early eyewitness testimony, the text of which is thoroughly documented, coming from a man of impressive moral character, who put himself under oath for his statements. It is difficult to imagine anything better.

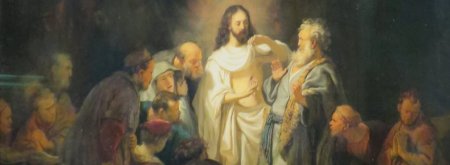

Learning from Thomas

The resurrection event did not happen in a vacuum. The gospels reveal Christ to have taught the highest ethic the world has ever heard, to have lived a life of stunning integrity, courage and compassion, to have performed astonishing deeds, to have consistently spoken with the authority of God, and to have been executed for blasphemy.

An incident in John’s account is instructive. Thomas had been told that this Christ had risen, by people he knew well and might reasonably have trusted, namely the other apostles. He had every reason to take them seriously, yet his doubts overwhelmed him. John reports that Christ later appeared to Thomas, eliciting his famous response “My Lord and my God.” Christ’s reply to him, however, is salutary. “Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed” (John 20:24-29).

In other words, all over the world, throughout the centuries, people would be invited to trust the risen Christ on the basis of the apostles’ clear and compelling testimony. That should have been enough for Thomas – and it should also be enough for us.

References

[1] See his website www.garyhabermas.com.

[2] C.H. Dodd The Founder of Christianity Fontana 1971.

[3] Gary R. Habermas The Risen Jesus & Future Hope Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield 2003, Chapter 1.

[4] Geza Vermes The Resurrection, Penguin 2008. On page 1 he states the most likely date is Friday 7th April AD 30, corresponding to the eve of the Passover full moon. Whether or not that is so, he writes that “the debate will remain firmly set in the real world of history and law, Jewish and Roman.”

[5] His prominence as a leader is confirmed by Josephus Antiquities 20.200.

[6] Josephus records that the High Priest Ananus had James stoned to death in AD 62. Eusebius records that Paul was decapitated and Peter was crucified in Rome under Nero, c. AD 64.

[7] Kittel and Friedrich, editors. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament Eerdmans 1985.

[8] Vermes (op. cit.) notes that the population of the whole of Palestine in 1926 was about 600,000 and was unlikely to have been higher in the first century AD. Most of the inhabitants lived and worked in the country (page 57).

© 2008 Peter May