The Resurrection of Christ in Matthew's Gospel

In this article, we shall look at Matthew’s account of the resurrection of Christ in Chapter 28 of his Gospel. In particular we will consider the women at the tomb, the dilemma of the guards, the scheming of the priests, the implications of grave robbing, the credibility of the story and the final encounter at Galilee.

The Women (verses 1–10)

Forty years ago, J.B. Phillips, a famous translator of the New Testament into contemporary English, wrote an influential little book called The Ring of Truth. In it he collected numerous examples of surprising details in the documents, which he contended could only have been included because they were true.

The involvement of women as the principal witnesses on that Easter Sunday morning is a typical example. It seems strange to us, but in first century Jewish society women were not accepted as being as reliable as male witnesses. The Rabbis taught that their testimony should only be considered if no males had seen the events in question. Yet here we have Matthew writing as a Jew and particularly for Jewish readers. If this was fictional, it is difficult to imagine why women should be the central witnesses to that pivotal event. Their testimony would seriously weaken the story. Surely the Gospel writers included them only because they were there. That is the way it was.

By the same token, Paul, writing his formal list of witnesses to the resurrection in 1 Corinthians 15, does not mention them. Female witnesses would do nothing to strengthen the case. Matthew, however, tells us (Matthew 27:61) that these two Marys had also witnessed the burial about 36 hours previously.

The earthquake (Matthew 28:2) was presumably an after-shock of the earthquake described during the crucifixion (Matthew 27:51). The region is vulnerable to earthquakes, being at the northern end of the Great Rift Valley, a fault line between two tectonic plates in the earth’s crust, which extends from deep in Africa up to the Jordan Valley.

Matthew’s previous reference to angels is in his birth narrative at the beginning of the Gospel story. Now this stunning apparition enters the scene. Incidentally, Luke says there were two angels (Luke 24:4). Such discrepancies should not faze us. Rather, they suggest that there was no collusion or attempt to bring the stories into line. Every jury smells a rat when the witnesses give exactly the same story. Here Luke records that Peter ran to the tomb; John adds that he ran with him; Mark and Matthew omit these details. Mark and Luke tell of two disciples who met Jesus while walking in the country; Matthew and John omit that. Luke says they gave Jesus something to eat; Mark doesn’t mention food on that occasion. Matthew and Mark record the instruction to go to Galilee; John doesn’t mention that but records a whole chapter about the appearances in Galilee, where they ate breakfast together on the beach. They all describe Christ’s final commands to them, but express them somewhat differently.

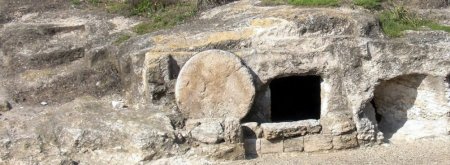

If there were two angels at the tomb, then Matthew was certainly right to mention one, so neither statement is intrinsically false. The angel rolls back the stone and sits on it. Interestingly, we are told nothing about the actual resurrection of Jesus. The angel doesn’t open the tomb to let Christ out. He has, it seems, already risen. Rather, he opens the tomb to let them in. We read in verse 6: 'Come and see the place where he lay'.

The arrival of the angel shook the guards witless and terrified the women. Mark and Luke say that the women took spices with them to anoint the body. They clearly had not been expecting anything else to happen. The angel tried to reassure them and sent them off to tell the disciples to meet the risen Jesus in Galilee. I suspect the women dropped the spices!

The angel told them to go quickly, but why did they run? Students of physiology will know the answer to that. Adrenaline is the hormone that is released for fright, fight and flight. If you are severely shaken, the desire to run is instinctive and very effective in reducing adrenaline levels and relieving stress. Exercise is good therapy for the anxious. They were 'afraid yet filled with joy' (verse 8).

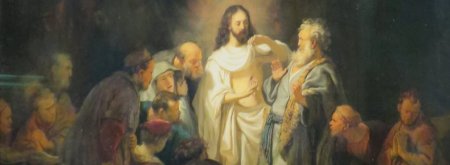

Suddenly the women met Jesus, their fear being all too apparent. So he further tells them not to be afraid and confirms the message of the angel about the rendezvous in Galilee. Matthew adds the important detail that this was no apparition or vision or flight of fantasy. This resurrection was not purely spiritual, for they physically clasped his feet.

The Guards (verses 11–15)

The scene now moves to the other witnesses to the story, the guards. Having recovered from their profound shock (verse 4), the guards went off to report the matter to the Chief Priests. Pilate had given permission for the deployment of the Guard, so these were probably Roman soldiers. His permission would not have been required for a deployment of the Jewish Temple guard. But reporting back to Pilate raised real difficulties: what would they tell him? To admit to such bungling incompetence, compounded by a story of such total improbability, would not go well for them. It could well have cost them their lives. So they go instead to the chief priests.

A cunning plan? (verses 12–15)

The priests, we read, consulted the elders and between them they devised a cunning plan (verse 12). Just how cunning was this plan? It constituted a complete volte-face. The previous day, they considered the stealing of the body and the claim of resurrection in fulfilment of Christ’s own prediction, to be the worst possible scenario (Matthew 27:62–66). Now they promote it as their best option.

It was not going to be easy. If the guards feared for their lives, persuading them to use the excuse that they were asleep was hardly going to help their cause. It required a sufficient sum of money to bribe them (verse 12) (bribery being the popular technique for getting what you wanted in that world) along with strong reassurances that the chief priests would speak up for the guards and keep them out of trouble (verse 14).

There were also intrinsic improbabilities about the idea that the guards slept through the noise of the tomb being opened and robbed; and being so deeply asleep, they still knew it was the disciples who did it (verse 13). This was not going to be an easy story to tell!

As a general rule, it is of course easier to be truthful than to lie, because fabrications create even greater difficulties. This lie, which was evidently told for years to come (verse 15), inadvertently bears witness to the unassailable truth (which they would have been reluctant to admit otherwise) that the body of Christ was not available to be able finally and comprehensively to refute the resurrection story. All they needed to do to stop the claim in its tracks was to produce the body. Everyone – the Roman soldiers, the Jewish Elders and the Christian disciples – were now all singing from the same song sheet; the one thing they all agreed upon is that the corpse had gone missing.

There are other difficulties with the guards’ story. While fire-fighters are well skilled at rescuing bodies by throwing them over their shoulders and carrying them off to a place of safety, they could not possibly do that with a 'stiff'. Rigor mortis sets in shortly after death and lasts for some 24 hours, and longer in a cool environment. Even if the stiffness was abating, there is a great deal of difference between lifting a conscious person and lifting an unco-operative 'dead weight'. I have some experience of this. As a GP, I have had to examine bodies at the Undertakers prior to a cremation. I find I cannot even push a body onto its side without help. Corpses are very difficult to manhandle. Trying to move a corpse usually requires two people. To take a corpse any distance requires several people. Usually four or six people carry a coffin into church, for instance.

Then there is the problem of disposal of the body. Murderers are driven to great lengths to accomplish this, and even then the body is usually found. If they try to bury it, the grave is usually too shallow. Some have tried dissolving the body in acid; others have chopped the body into pieces and thrown it into a lake. This body was apparently lost without trace.

Here, then, we have a scenario which would require several witnesses to the crime, all of whom take their secret to their graves, despite the phenomenal rumpus occurring by large numbers of people fraudulently claiming that they had seen Jesus alive after death. How come nobody broke rank and spoke up or even left an anonymous diagram to say where the body could be found?

Modern Sceptics

It comes as a surprise to modern sceptics that anything intelligent can be said 2000 years after the event to defend the claim that Jesus rose from the dead. However, the passage of time in itself does not weaken the evidence. The evidence is dependent on the time lapse between the events themselves and the recorded witness statements. The force of that evidence does not then weaken over the years, apart from the inability to interrogate the witnesses.

The more the story is studied, the more perplexing it becomes. There are of course, two quite separate matters that have to be resolved. Firstly, a plausible explanation is required to account for the empty tomb and the missing body. Secondly, some credible explanation is required to account for the experiences of all those people who claimed to have met the risen Christ. Illusions and hallucinations do not fit the picture at all. Paul tells us in the oldest account, that this list included 500 people at one time (1 Corinthians 15:6), most of whom were still alive when the document was written. Given the enormous numbers of people, who became convinced of this story from the outset, some such number would be required.

We haven’t got space here to review all the schemes that have been put forward and the enormous lengths unbelievers have gone to, to reconstruct a ‘credible’ alternative scenario. We can briefly consider a typical example.

Some have postulated that Jesus recovered in the cool of the tomb and escaped while the guards slept. The problems with this are many. Firstly, we are assured he was dead before being taken down from the cross, hence the spear in his side (John 19:34). Roman soldiers were all too expert at the work of crucifixion – they had plenty of practice – and were too fearful of the consequences if they made a bad job of it. Even if he was alive, without First Aid to stem the blood flow and a drink to replace his fluid loss, it is difficult to imagine how he could recover from such physical extremis. Then to postulate that he found enough strength to remove the stone just when the guards – all of them – were in complete dereliction of duty by being deeply asleep, increases the implausibility. You then have to suppose this dying man so appeared to his disciples that they thought he was resurrected. We are not told how he got to Galilee on pierced feet. It certainly wasn’t by bus. We must assume he lived in isolation from anyone else and finally, sooner or later, died. Yet, somehow his death and burial went unnoticed and pilgrims never flocked to his tomb.

Unless you are an intellectual ostrich, who just sticks his head in the sand when you come up against a difficulty, intellectual integrity demands that you look for a credible option. Bertrand Russell, for instance, in his book Why I am not a Christian, ducked the issue completely, while Richard Dawkins feels the matter is beneath him.

Now I first approached this story as a sceptic. My assumption was that it was obviously not true. Dead men don’t rise; we all know that. This was so central in my thinking that I read the New Testament sifting out all references to the resurrection from conscious thought or analysis. It was only on reading it a second time that I began to see the size of the problem. This was not an insignificant detail that could be marginalised from the story or swept under the carpet. It was the central event. Any credible conclusion that could be drawn about the person of Christ had to include a view on this matter. The more I looked at it, the more difficult it became.

The turning point for me was this, and it was for me a ‘eureka’ moment. It was like the sensation you have when you slam the front door and walk three paces down the drive, only to realise you have left the key inside. A warm, rather disconcerting glow comes over you. Now what do you do?

My realisation was this. Whatever the truth of the matter – and I was still a long way from believing it – this much was quite clear: for some reason or another, the disciples did actually believe it was true – and did so wholeheartedly. That was a psychological certainty. They might have been deceived, but if so, they were totally taken in. Their behaviour from the outset was consistent only with their wholeheartedly believing it. They were irrepressible. They took the ancient world by storm and with great urgency proclaimed that this was the greatest truth of all, that God had raised Jesus from the grave. They could not be stopped. Though it cost them their lives, they pressed on, going far outside their own comfort zone, to the ends of the known earth. No-one disputes that the Christian faith spread on the vitality and conviction of their message.

They believed it – and believed it passionately. The early church could never have got off the ground if they doubted the story or were knowingly telling lies. Lies make people into cowards, not heroes.

This is to my mind the pivotal issue. You have to construct a scenario both about the tomb and their subsequent experiences, to cause this level of certainty. There is only one explanation that can do that – it is the one that Matthew gives us in his gospel.

Of course, we are not talking about a resurrection in a vacuum. It is not that some isolated, unknown individual defeated death for inconsequential reasons. No. We have got to look at the whole picture.

We are talking about the most extraordinary person to have walked the pages of history. Someone who gave the world the most sublime teaching it has ever heard; who in his life and character provided the finest example of compassion and virtue ever witnessed; who performed the most extraordinary deeds. Someone who spoke with the authority of God; who made the most extreme claims about his own identity and purpose; and who died a ‘sin-bearing’ death that was vividly predicted by the prophet Isaiah (chapter 53) over 700 years beforehand. To their deaths and the ends of the earth, the disciples testified that God had raised this Jesus from the dead. They did so with such compelling vigour that wherever they went, people actually believed them. As the Cambridge scholar C.F.D. Moule said on the radio many years ago, 'You have to find a launching pad to launch this missile'.

The Final Rendezvous (verses 16–20)

Matthew concludes with the final rendezvous on a mountain in Galilee. Why Galilee? Well, you may remember that it was in Galilee where Jesus first called the disciples to leave their nets and follow him (Matthew 4:18 ff). It was in Galilee they climbed a hill and he delivered the most famous sermon of all time (Matthew 5, 6 & 7). Now he calls them back to Galilee to give them their final briefing. This Jesus, whom the wise men believed was the King of the Jews (Matthew 2:2), now makes the most extreme claim, 'All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore go to all the nations of the world to make disciples, teaching them to obey everything that I have taught you and baptising them in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit' (Matthew 28:18–19).

It was a colossal undertaking. As J.B. Phillips put it, 'It is a sobering fact of history that such a few men made such a significant impact.' For a colossal task Jesus gave them a colossal promise, which was itself a result of his resurrection. Matthew recorded at the outset (Matthew 1:23) that this baby would be called Immanuel, which means 'God with us'. God was with them throughout Christ’s life on earth. Now because of his resurrection, he promises to be with every believer in every generation to the end of time (verse 20).

Furthermore, there is no situation we can get ourselves into, where God is not with us. He is there when we meet to sing his praise; he is with us when we study his scriptures and share the bread and wine in the Lord’s Supper. But he is with us also when we doubt him and when we are tempted. He is there when we are alone, even in our darkest moments, when we wish the earth would swallow us up.

We don’t have to plead with him to join us, nor go through any ritual to attract him to us. The promise is there for all believers at all times, that he will never leave us. All that is required of us is to recognise that fact and trust him in every deed, every circumstance, every encounter, every tragedy and every joy. He is the Lord of history and we must construct our lives, our behaviour, our hopes and our ambitions around his resurrected presence so that he is truly Lord of our lives also.

Now that is something to get excited about!

© 2008 Peter May