The Kite Runner

Khaled Hosseini’s best-selling novel The Kite Runner, set in the author’s homeland Afghanistan, became a Hollywood blockbuster when it was made into a movie last year. With the film now widely available on DVD, Jenny Ivers takes a look at the story’s themes of guilt, self-discovery and redemption.

“There is a way to be good again”

These words from an old friend and former mentor down a distant phone line catapult The Kite Runner’s protagonist, Amir, back to a childhood moment he has tried in vain to forget. His “unatoned sins”, as they are described in the novel’s opening chapter, have plagued his conscience and cast an oppressive shadow over his joys and triumphs. The phone call interrupts Amir’s seemingly comfortable life as a married man and newly-published novelist in America, and launches an epic journey back to Afghanistan in search of redemption.

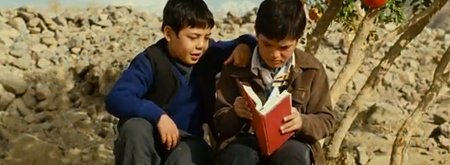

The story rewinds to Amir’s childhood in Kabul where he grows up alongside Hassan, the son of his wealthy father’s servant. It is an unequal friendship – Hassan adores Amir while the latter takes advantage of the former’s unswerving faithfulness. The object of Amir’s affections meanwhile is his father, whom he longs to please while being painfully aware that he is something of a disappointment. Worse still is the sense that his father – his ‘Baba’ – would prefer Amir to be more like Hassan. This ‘love triangle’ drives the actions of the young boys, culminating in a devastating moment when Hassan makes a painful sacrifice for his friend while Amir looks on and fails to intervene.

The novel is narrated by an adult Amir and while the film is faithful to The Kite Runner’s plot and characterisation, it isn’t able to convey the protagonist’s honest self-reflection as he recalls events. Here is the pivotal episode which at the start of the novel Amir says “made me what I am today”:

I had one last chance to make a decision. One final opportunity to decide who I was going to be. I could step into that alley, stand up for Hassan – the way he’d stood up for me all those times in the past – and accept whatever would happen to me. Or I could run. In the end, I ran.

I ran because I was a coward. I was afraid of Assef and what he would do to me. I was afraid of getting hurt. That’s what I told myself as I turned my back to the alley, to Hassan. That’s what I made myself believe. I actually aspired to cowardice, because the alternative, the real reason I was running, was that Assef was right: Nothing was free in this world. Maybe Hassan was the price I had to pay, the lamb I had to slay, to win Baba. (The Kite Runner, p.68)

Amir looks back as his 12-year-old self is confronted with the reality of who he is, the depravity of his heart and the selfishness of his motives. The young boy can’t bear it and as his guilt deepens, it creates an ever-expanding gulf between Amir and Hassan. The sacrificial ‘lamb’ is a constant reminder to Amir of his sin, and he contrives a way of getting Hassan out of his sight for good.

Years later, following the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, Amir and his father leave their homeland and set up a new life in America. Amir achieves a college degree, meets the woman who becomes his wife, and launches his dream career as a novelist.

But he cannot escape the guilt of his past and – following the phone call from his former mentor – Amir sets off for Kabul on a quest “to be good again”. And the steps he must take on the road to redemption prove to be physically and emotionally painful. We wince as we watch Amir take a beating from Assef – Hassan’s attacker and now abusive master of his son Sohrab – but the film scene is actually a toned down version of the novel’s graphic description.

Amir can’t undo his childhood crimes and it is too late to seek Hassan’s forgiveness, but he takes the opportunity to go over familiar ground and act as he should have then. He is sacrificial rather than selfish, and courageous instead of cowardly as he becomes the fearless defender of Hassan’s orphaned son. In Amir, Hosseini creates a rounded and truly sympathetic character. We can identify with his deep regret over past mistakes and desire to go back and make amends. In the literary sense, Amir does redeem himself and we are rooting for him, rightly admiring his transformation.

The Kite Runner is a compelling story and if you were moved by the film you will cry buckets at the novel. Hosseini makes us believe that it is possible “to be good again” by taking the punches we deserve and playing the part of the hero we wished we were. But unlike fiction we can’t create the scenarios that enable us to retrace our steps and play out events differently. The reality is that all too often we find ourselves in similar situations succumbing to the same character failings and repeating mistakes again and again.

The gospel tells us that it is impossible to redeem ourselves by human effort. But it also tells us that there is a way for fallen people “to be good again”.

The apostle Paul, writing to the Ephesians, describes man’s helpless state as “dead” in “transgressions and sins” (Ephesians 2:1). A dead person clearly cannot bring himself back to life and Paul emphasizes the point that a person’s salvation is entirely God’s work:

But because of his great love for us, God, who is rich in mercy, made us alive with Christ even when we were dead in transgressions – it is by grace you have been saved.(Ephesians 2:4-5)

God makes us alive with the resurrected Christ, who in his death on the cross bore the penalty our sin deserves, when we believe the gospel. And trust in that gospel, itself a work of God in us, is the only way we can truly become good. Paul continues:

For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith – and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God – not by works, so that no-one can boast. For we are God’s workmanship, created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do. (Ephesians 2:8-10)

Having saved us from the consequences of our sin, God re-creates us, making us like the One who rescued us – enabling us to be good.

© 2008 Jenny Ivers