Can We Be Free Without God?

Since the days of Lucretius in Ancient Rome, the very idea of God has aroused hostility in the hearts of many who deny or question his existence. Whilst great composers like Bach and Handel have celebrated God as Creator and Saviour in imperishable music, countless atheists have affirmed their conviction that religious belief is rooted in fear, insecurity, and the worship of power.

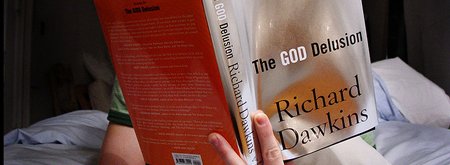

‘If God existed, it would be necessary to destroy him’, declared the 19th century Russian anarchist, Bakunin, in his famous pamphlet, God and the State. Today that view is echoed in the works of best-selling novelists like Philip Pullman and the late Ayn Rand, and in the writings of Darwinian scientists like Richard Dawkins. But perhaps the clearest expression of theophobic atheism has come from the pen of Britain’s best-known 20th century philosopher, Bertrand Russell.

In a lecture on ‘Why I am not a Christian’, delivered in 1927 to the South London Branch of the National Secular Society, Russell concluded:

We want to stand upon our own feet and look fair and square at the world – its good facts, its bad facts, its beauties, and its ugliness; see the world as it is, and be not afraid of it. Conquer the world by intelligence, and not merely by being slavishly subdued by the terror that comes from it. The whole conception of God is a conception derived from the ancient Oriental despotisms. It is a conception quite unworthy of free men. When you hear people in church debasing themselves and saying that they are miserable sinners, and all the rest of it, it seems contemptible and not worthy of self-respecting human beings.

These words, spoken over 76 years ago, remain an accurate reflection of contemporary theophobia. For many people, belief in God is associated with irrationality, life-hating asceticism, and intolerant fanaticism. To be a Christian, they think, involves a soul-destroying surrender of one’s whole being to a cosmic tyrant whose chief claim on our obedience is that he is all-powerful and will destroy us if we reject him. Not only is this idea repugnant; it is the evil root of all religious persecution because it denies the legitimacy of freedom of conscience. In addition, many atheists believe, religious faith is inimical to scientific progress because it demands unquestioning submission to the authority of the Church, and uncritical adherence to religious dogmas.

Some readers may be tempted, at this stage, to doubt the significance of theophobic atheism in our relativistic, yet spiritually hungry, post-modern culture. If so, the huge popularity of Philip Pullman’s theophobic anti-Christian fantasy trilogy, His Dark Materials, should make them think again. Although a work of fiction, its author does much more than simply tell a good (and sometimes moving) story involving two children. He skilfully enlists the reader in his crusade against traditional religion by the simple device of caricaturing its doctrines and painting its fictional protagonists in the blackest possible colours.

Their principal opponents, by contrast, are portrayed as an eclectic but attractive band of freedom-fighters, caught up in a cosmic struggle against spiritual oppression and cruelty. Furthermore, by ensuring that the ‘good’ rebels in his story include beautiful witches and angels, Pullman is able to satisfy popular craving for the supernatural whilst simultaneously exploiting the resentment many people feel against God because of the existence of evil and suffering. That he should have achieved such commercial and critical success in attaining these goals, shows the cultural resonance of contemporary theophobia.

As a former atheist, I can understand why so many individuals dislike the concept of God and disbelieve in his existence. All too often, history records, the worship of God has been associated with hatred, intolerance and the abuse of power. The horrors of the Inquisition, the witch-hunting crazes of the 16th and 17th centuries, the ‘wars of religion’, anti-semitic pogroms – all are grim examples of the crimes committed in God’s name by those claiming to be His followers. To quote C.S. Lewis, who was himself an atheist before his conversion to Christianity: ‘If ever the book which I am not going to write is written it must be the full confession by Christendom of Christendom’s specific contribution to the sum of human cruelty and treachery. Large areas of ‘the World’ will not hear us till we have publicly disowned much of our past. Why should they? We have shouted the name of Christ and enacted the service of Moloch.’ (The Four Loves, Fontana Books, 1976, p.32).

Appreciating the motives behind honest atheism should not, however, be confused with acceptance of its theophobic claims. As this article will argue, it is atheism – rather than belief in God – which is irrational and inimical to liberty. It is philosophically untenable, theologically perverse, and, above all, fuelled by a one-sided and distorted interpretation of history.

To open the case for the prosecution: why is atheism irrational? In the first place, because it cannot provide a convincing explanation for the existence and complexity of life in all its myriad forms. To accept atheism, you have to believe that our extraordinary universe, with all its amazingly intricate structures, processes and organisms, is merely the accidental product of random physical and chemical events. But is this remotely credible? Is it really likely, for example, that the human body’s immune system or the migratory and nest-building instincts of birds are just biological accidents? And what about the navigational systems of bats and whales, or the structure and operation of the genetic code? Are these also the unintended results of an accidental universe? If, as all would acknowledge, the most sophisticated modern computers have only come into being as a consequence of the deliberate application of human intelligence over several decades, is it credible that the infinitely more complicated human brains that created them emerged by a fluke within an idiotic cosmos?

And anyway, why is our universe a cosmos and not a chaos? How do atheists explain the fact that the universe appears to be governed by a few simple laws of physics, so that its order and structure can be expressed in terms of mathematics? Does this not point to the existence of a Supreme Mind behind the ‘architecture’ of our world? Why, if there is no Divine Intelligence behind the universe, have most of the great thinkers of Western civilisation thought the opposite – from Plato and Aristotle to Francis Bacon, Newton, and Einstein? Even famous sceptics like David Hume and John Stuart Mill acknowledged the apparent strength of the argument from design – the ‘teleological proof’ of the existence of God.

‘The whole frame of nature bespeaks an intelligent author,’ commented Hume, in his essay on The Natural History of Religion, ‘and no rational enquirer can, after serious reflection, suspend his belief a moment with regard to the primary principles of genuine theism and Religion.’ A century later the same view was expressed in Mill’s essay on Theism: ‘[T]he adaptations in Nature afford a large balance of probability in favour of creation by intelligence.’ Nor have such telling admissions been confined to the ranks of the great British philosophical critics of conventional religion. Even so fierce an opponent of Christianity as Voltaire, the greatest figure of the French Enlightenment, expressed his belief in the existence and goodness of God, complaining only that the Church had distorted and dishonoured true religion by associating it with superstition, intolerance, and cruelty.

Atheists commonly rely on two arguments to justify their rejection of the powerful evidence for the existence of an Intelligent Creator. The first, and oldest, is the problem of evil. How can a world marred by pain, suffering, and death, be the creation of an infinitely good, loving, all-knowing, and all-powerful God?

I used to think, when I was an atheist, that this objection was a decisive one, but this is illogical. The problem of evil is simply another (albeit terrible) piece of the puzzle of existence which needs to be fitted into its proper place within the overall picture of reality. It does not cancel out the evidence for Intelligent Design. To believe otherwise is equivalent to saying that because hatred exists within some families, there is no such thing as human love; or that because there are badly constructed buildings in one town, intelligent architects do not exist. In any case, atheists cannot use the problem of evil as a credible argument against the existence and goodness of God, because to do so depends on the assumption that the moral standard by which they judge the world around them is an objective one, and that assumption is hard to reconcile with atheism. If we and all our thought processes are only the accidental and unintended by-products of an ultimately random and purposeless universe, how can we attach any significance to our beliefs and values? If, on the other hand, our moral convictions are eternally true insights into reality, does this not suggest that there is, after all, an eternal Goodness and Intelligence behind all things?

The difficulties atheists face in trying to explain moral awareness is but a reflection of their inability to provide a convincing explanation of human consciousness in general, an important theme to which I will return later. But at this stage of the argument it is time to consider their other principal objection to the existence of an Intelligent Creator: namely, the Darwinian theory that the appearance of ‘design’ in Nature can be explained in terms of naturalistic evolution. According to this view, which it is heretical to even question in our secularised post-Christian Western culture, the action of natural selection on random mutations has ensured, over millions of years, the emergence and survival of new and increasingly complex life-forms and species, so well adapted to their environments, that they foster the illusion of having been deliberately created by a Divine Intelligence. In reality, of course, so the argument runs, these adaptations are merely the work of unguided natural forces acting the part of a ‘blind watchmaker’ – to use the phrase popularised by Richard Dawkins.

Of the growing scientific critique of naturalistic macro-evolution, I will say nothing other than to point out that there are literally thousands of scientists in the English-speaking world who now reject Darwinism. I would, in addition, challenge any atheists who doubt the existence of cogent scientific arguments against evolution, to examine the powerful case against it set out in Michael Denton’s Evolution: A Theory in Crisis (Adler & Adler, 1986) and Michael J. Behe’s Darwin’s Black Box: the biochemical challenge to evolution (Simon & Schuster, 1996). But even if one ignores the strictly scientific objections to Darwinism, the philosophical case against naturalistic macro-evolution is overwhelming.

Darwinian evolution lacks all credibility as a theory because the accidental emergence of complex organs and life-forms does not become more probable by being divided up into many little steps over a long period of time. Since, according to atheists, the evolutionary process is ‘blind’, in that it has no conscious purpose and therefore no final ‘target’ at which it is aiming, there is no reason why all the little steps required for the development of the human eye, for example, should occur at the right time and in the right order. In fact, the chances of this happening are too remote to be taken seriously. Consequently it is hard to see how atheistic Darwinists can explain the development of living things without reference to God, since they have to account for the existence of thousands of complex structures and creatures, not just one. Nor is this the worst problem facing them. The real challenge confronting atheists, whether they are Darwinian scientists or theophobic novelists, is to explain to the rest of us why we should believe that blind, unguided natural forces are a more probable cause of the existence and order of the universe than an Intelligent Creator!

Atheists face an equally formidable problem nearer home. They cannot provide an adequate explanation for human consciousness. In particular, they cannot account for our ability as human beings to think, choose, and discover moral values.

We are accustomed, in ordinary conversation, to dismiss any argument if it can be shown to rely wholly on prejudice or some other irrational factor or premise. But if atheism is true, our minds are wholly dependent on our brains (because we have no souls) and our brains are only accidental by-products of the physical universe. This means that all our thoughts, beliefs and choices, are simply the inevitable result of a long chain of non-rational causes. How then can we have free will or attach any validity or importance to our reasoning processes? If we are bound to think or behave the way we do because of our internal biochemistry, how can we be free agents or know that we are in possession of objective truths about science, ethics, or politics? If our perception and use of the rules of logic are merely the inevitable end product of a long chain of random and purposeless physical and chemical events, how can we know that our examination of facts and arguments yields real knowledge? Surely, if atheism is true, our thoughts and values have no more significance than the sound of waves on a seashore, as C.S. Lewis argued at length and so convincingly in his famous book, Miracles[1]. Indeed, even some atheists have recognised the extent of the problem of knowledge for philosophical materialists. To quote one famous Marxist scientist of the 1940s, Professor Haldane: ‘If my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain, I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true...’ (Possible Worlds). In other words, atheistic materialism refutes itself because it discredits all reasoning, including the reasoning required to justify atheism.

The truth, then, is that we can think and reason correctly, since the argument that we can’t, in itself involves an act of reasoning and is therefore self-contradictory. We cannot ‘know’ that we know nothing! Our belief that we have free will is similarly valid, not only because we are aware of our capacity to choose between alternatives and change our minds, but because the denial of free will also involves the use of a self-contradictory argument. If all our reasoning is solely ‘determined’ by our physical constitution and is therefore not ‘free’, so too is the belief that we have no free will, so how can we know that it is true? It is, again, an argument that refutes itself.

But if logical reasoning shows us that atheistic materialism cuts its own throat over the problem of knowledge and free will, how can we explain our ability to think, know, and choose? Surely the best answer is that we are spiritual as well as material beings, and as such, we are the creation of an eternal, self-existent Intelligence outside ourselves and the physical universe, from whom we derive our inner freedom and rationality. Our minds can discover truth because they are illuminated by the Divine Reason. Our spirits are similarly free because free will is a gift of the Omnipotent Creator. In short, we are, as the Bible tells us, made in the image of God.

Atheism is no more successful in explaining moral awareness without reference to God, than it is in trying to account for reason and free will. Just consider the usual secular alternatives.

We cannot explain away our innate sense of right and wrong by saying that our moral perceptions are instincts, since our instincts are often in conflict with each other, and are themselves in need of moral adjudication before we can know how we ought to act. Our feeling that we ought to repress our survival instinct in order to follow our instinct to rescue a drowning child who has fallen into a freezing lake, for example, results from our awareness of a moral obligation to save life and relieve suffering. The question, however, is where does this sense of moral obligation come from? It is obviously not an expression of our desires and emotions, since our moral sense is often in conflict with them. We want to commit adultery with attractive women but we know we ought not to break our marriage vows. We get angry with a person who challenges our political views, but we control our tempers because we know we ought to respect the freedom of thought and speech of others.

Can our moral sense be explained away along Darwinian lines, as an aid to survival developed over many centuries of human existence? Surely not. As even the briefest survey of history and our daily newspapers will confirm – not to mention our own personal experience – kindness, fair-mindedness, and integrity, are often a hindrance, not a help, to advancement in business, academia and politics. If moral goodness really has survival value in the ‘jungle’ of human society, why have there been so many wars, and why are there so many successful criminals and dictators?

What about the most promising non-theistic explanation of morality, that of social utility? What is morally good means what is good for society. Is that not a sufficient and complete explanation of our moral understanding? Theft and murder, for instance, are evils because they are destructive of the lives and property of other people, and therefore make it more difficult to live together in harmony. Lying in court is wrong, because false testimony can lead to a miscarriage of justice. Don’t these arguments give us an objective basis for morality without any need to invoke the existence of God? But all this only begs the key question. Why should we care about the rights and interests of other people if, because of our superior strength and cleverness, we can have a more enjoyable life by trampling over them?

In the end, unless we are moral nihilists, we must recognise that our moral perceptions about the value of life and liberty, and the rules we must obey to safeguard society, are self-evident truths or axioms. As such, they are as rational and objective as the rules of logic, and failure to understand them is the moral equivalent of colour blindness. But if this is the case, how can it be explained or justified if human beings are only biological machines put together by chance in an accidental and purposeless universe? How can their moral ‘thoughts’ have any meaning or significance? Only, surely, if the Moral Law ‘written on our hearts’ is somehow a reflection of an eternal, self-existent ‘Goodness’ outside ourselves and ‘behind’ or ‘beyond’ the physical order of Nature. And since moral knowledge, like all knowledge, does not exist in a vacuum but is grasped and possessed by intelligence, that eternal Goodness which illuminates our consciences must somehow be grounded in, and the self-expression of, the Supreme Mind or Spirit to which all life owes its being, in other words, God. Or to put it more simply: God is Goodness and Intelligence personified.

Theophobic atheism, then, is philosophically bankrupt. It cannot make sense of life or provide a secure metaphysical foundation for moral values, because it can neither provide a convincing explanation for the existence and order of the universe, nor can it account for human consciousness. Ironically, it cannot even provide a secure metaphysical basis for science! Belief in a rational Creator preceded the rise of empirical science in the West, because it alone provided the necessary assurance that the universe was orderly and therefore capable of being systematically investigated. If, however, the great scientists of the past had not believed in God (as all of them did – e.g. Kepler, Galileo, Copernicus, Boyle, Newton, etc.), what reason would they have had for imagining that there were any ‘laws’ of Nature to discover in the absence of a Lawgiver?

Theophobic atheists are not only wrong in thinking that religion is necessarily the enemy of scientific progress; they are even more tragically mistaken in their belief that religious faith is incompatible with liberty.

At the philosophical level, liberty would have no function or purpose were it not for the fact that we value human life and happiness, and believe that freedom is essential for the release of personal creativity and the pursuit of knowledge, truth, and virtue. But if freedom is valued for these reasons, this implies that it only has meaning and significance within an objective and eternal moral order, and, as we have seen, such a moral order itself points to the existence of God. Furthermore, the growth of liberty and constitutional government owes a critical debt to the Judeo-Christian view of human life and destiny. It is precisely because human beings are made in the image of God, and are therefore the children of a good and loving Creator, that it is wrong to kill, injure, or oppress them. That is the main reason why liberal democracy developed in the West, and why Christian sentiment played such an important role in the anti-slavery campaigns of the 19th century, and in the growth of humanitarian legislation during the same period.

The crimes committed in the name of religion, whether perpetrated by the Spanish Inquisition in the 16th century or by Islamic tyrants and fanatics in the 21st, do not discredit belief in God. They merely reveal the hypocrisy and moral frailty of many religious leaders, and in doing so, underline the truthfulness of the Biblical doctrine that human nature has been morally corrupted by rebellion against God. In particular, they remind us that it is precisely because human nature is ‘fallen’, that it is essential to limit the power of the State and prevent it being used to buttress the Church and stifle dissent. They also remind us that since free will is a gift from God, neither Church nor State has the right to coerce the conscience of the individual.

The sad truth is that it is theophobic atheism, not religious faith as such, which is inimical to liberty. At the political and social level, it undermines people’s belief in the ultimate value of life and the existence of an eternal Moral Law and Judge by which and by whom they will eventually be held to account. This in turn encourages amoral attitudes and behaviour, and the belief, in politics, that the State is supreme and the ends justify the means. The results in the twentieth century? The growth of crime and delinquency in increasingly secularised Western societies, and the advent of the bloodiest political tyrannies in history. Perhaps Lenin best encapsulated the theophobic spirit of totalitarian socialism when he wrote in 1920:

We do not believe in everlasting morality, and we denounce all this lying rubbish about it.

His legacy? Over 100 million people killed by Communist dictatorships since 1917.[2]

The final charge against theophobic atheism is that it is theologically perverse. It misrepresents the nature of God and the necessary relationship between Creator and creature.

If reason (reinforced by revelation) tells us that God exists and is our Creator, it follows that God is the eternal source of all life, love, goodness, beauty, truth, and joy. It means that he is not only the Creator of the Universe, but also the author of our being and the source of our gifts, talents and rationality. How, then, can it ever be right to reject or disobey Him? How can we spurn the One who has created us, and given us the gift of free will, so that we can share his life, love and joy? How can we ever be justified in rebelling against the Divine Wisdom which alone enables us to think and argue? How can it be demeaning to worship the Divine Love and Beauty which is the true source of all that is precious and desirable in human existence? To refuse to acknowledge God’s claims on us is like a plant refusing to grow towards the sunlight. It is to commit spiritual suicide.

Can we be free without God? I leave the last word with one of the noblest figures in the history of liberty, the great 19th century Italian liberal, Joseph Mazzini:

If there be not a Supreme Mind reigning over all human minds, who can save us from the tyranny of our fellow men, whenever they find themselves stronger than we? If there be not a holy and inviolable law, not created by men, what rule have we by which to judge whether an act is just or unjust? In the name of whom, in the name of what, shall we protest against oppression and inequality? Without God there is no other sovereign than Fact; Fact before which the materialists ever bow themselves, whether its name be Revolution or [Napoleon] Buonaparte. (The Duties of Man)

Footnotes

[1] Miracles was first published in 1947, but revised and updated in 1960. It is now available as a Collins-Fount Paperback.

[2] For detailed estimates of the human cost of Communism, see The Black Book of Communism, by Stephane Courtois et al, Harvard University Press, 1999, and the relevant chapters in Death By Government, by Professor R.J. Rummel, Transaction Publishers, 1997.

© 2006 Philip Vander Elst