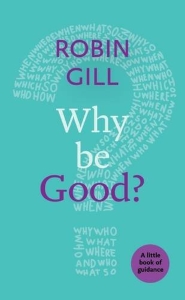

Why Be Good? - a review

Having largely severed ties with its Christian heritage, few questions present such difficulty to our modern society as this one. This is not to say that we are less moral than our predecessors; rather, many of us struggle to articulate precisely why we should be good. For that reason, Robin Gill’s Why be Good? seems a timely publication.

Sadly, despite the intriguing title and the high production value, this book has a handful of fatal flaws. It certainly doesn’t help that the book’s purpose is unclear from start to finish but the biggest problem is the repeated failure of the author to build any kind of argument, resorting instead to vague assertion, ensuring it is as unconvincing as it is brief.

Sadly, despite the intriguing title and the high production value, this book has a handful of fatal flaws. It certainly doesn’t help that the book’s purpose is unclear from start to finish but the biggest problem is the repeated failure of the author to build any kind of argument, resorting instead to vague assertion, ensuring it is as unconvincing as it is brief.

At only 48 pages and published in SPCK’s series of booklets called “Little Books of Guidance,” the book seems at first glance to be intended as a concise apology for Christian ethics. After an introduction in which he sketches out his plan for the book, Gill offers four chapters, each one an intriguingly entitled response to the proposed question:

- Because some things are evil

- Because if I scratch your back you will scratch mine

- Because it is our duty

- Because God is good

There is a frustrating lack of argumentation throughout

Presumably, the intention was for the argumentation to build throughout the chapters, paving the way for the fourth and final chapter, which would point the reader towards the biblical basis for much of our modern ethical code. However, there is a frustrating lack of argumentation throughout, and the last chapter only offers a vague description of religiously based ethics in general (as opposed to specifically Christian ethics), drawing in turn on the Jewish, Islamic and Christian faiths. The reader is left guessing at this booklet’s purpose; if it was to persuade the reader for the case for religious ethics, it failed badly. Nor does it engage the reader in any case for biblical Christianity.

Right from the first chapter, “Because some things are evil,” the propensity of the author to assert his view, rather than persuade the reader of it, is obvious. Failing to capture the heart of the problem of moral relativism, Gill begins the chapter by giving extreme examples of human evil. He quotes from the blurb of Simon Sebag Montefiore’s work on Stalin, describes the behaviour of mafia contract killer Richard Kuklinski and then uses testimony from a British soldier who liberated survivors from Belsen concentration camp in World War Two. Having presented these examples, Gill suggests that morality cannot merely be a matter of taste, and that we must therefore choose good:

If some things are deemed to be objectively evil, then it may be reasonable to conclude that other things are objectively good. And surely it is then reasonable to conclude that we should pursue the good and eschew what is evil. (6)

Gill has assumed almost everything his book is supposed to argue

The problem with this approach is that Gill has assumed almost everything his book is supposed to argue. He assumes that the examples he gives are “objectively evil,” assumes that some are therefore “objectively good” and assumes that we should therefore do good. While no one would disagree that contract killers who shoot people for fun and the Holocaust are evil, the purpose of the book is surely to show us why we should do good. Assuming the very thing you are attempting to prove is not only rhetorically disastrous; it renders your entire project pointless.

Sadly, the remainder of the work continues the trajectory that the first chapter begins. This is most notable in the third chapter “Because it is our duty,” where Gill frantically saws off the branch on which he sits by arguing that “a sense of duty is difficult to understand or justify in purely rational terms… [it requires] an act of faith on our part – a basic faith that we really should treat other people fairly and not exploit them for our own benefit” (21). By declaring that we cannot explain our sense of duty but must simply believe him, Gill effectively invites us not to think about the very question he has written a book on.

There are other problems with this work. Despite being short enough to necessitate concise and engaging writing, it is often rambling and imprecise. One bizarre instance comes at the end of the first chapter, where the author concludes by apparently undermining his own position for the sake of rhetorical flourish “It is then reasonable to conclude that we should pursue the good and eschew what is evil. Or is it?” (6). Many of Gill’s examples are odd and his digressions are distracting. Lastly, merely describing different religious approaches to morality in the concluding chapter hardly provides a robust argument for the value of religious faith; it is hard to know what Gill intended with this chapter.

Gill is an accomplished storyteller and he understands his subject matter well

There are, however, moments of value in the book. It is clear that Gill is an accomplished storyteller and the chapters all have compelling titles, showing that he understands his subject matter well. If they had been used effectively, this may have been a different book.

Having written prolifically on theological ethics over a lengthy academic career, not to mention his service on a number of medical ethics advisory panels, the contribution that Gill’s expertise has made towards the field of ethics is not in doubt. That said, this little book of guidance is not a good example of apologetic reasoning. Readers interested in the issue of ethics would be much better off picking up a copy of C.S. Lewis’s classic Mere Christianity.

Title: Why Be Good?

Author: Robin Gill

Publisher: SPCK

Publication Date: 2016

Pages: 48

Price: £3.99

© 2017 James Bunyan