Did Christ die on a cross or a stake?

The most famous person crucified was Jesus Christ. For approximately two thousand years a cross – with or without a body on it – has been the main symbol of Christians of all denominations and in all countries.

It was also a symbol used by the 'Bible Students', an organisation founded by Charles T. Russell in Pennsylvania in 1879. In 1931 this organisation adopted the title 'Jehovah's Witnesses'.

In 1921 they published the book The Harp of God, which has the subtitle 'Proof Conclusive that Millions now Living will Never Die'. By the time of the 1925 edition they had printed more than two million copies (precisely 2,327,000, according to the first page). On page 114 of this book there is a picture (see right), which occupies the whole page, of Christ being crucified on a cross, with the sign written by Pontius Pilate nailed above his head.

But in a change of doctrine, the Jehovah's Witnesses now say that Christ was not crucified; they say that he died on a pole or a stake. It goes without saying that this will astound not only millions of Christians around the world, but also historians. There have been and there still are those who reject the idea of the resurrection of Christ, but up until now practically no-one had doubted His death, nor the means of his execution.

Crucifixion consisted of forming a cross with two wooden beams, one vertical and the other horizontal. The person condemned to death was nailed to the cross, with nails through his hands or wrists and through his feet. The cross was placed in a hole in the ground, with the condemned person hanging by his hands. This usually caused death by asphyxiation, although sometimes people being crucified took days to die. The only respite, to help himself to breathe, was that the condemned person could (as long as he had strength!) push with his feet in order to raise the body a little and thus reduce the force with which the extended arms were pulling, constricting the chest, and in this way it was possible to take a further breath. Sometimes, when a person who was being crucified was taking a long time to die, the Romans broke his legs, and thus he was no longer able to raise his body and so died sooner from asphyxiation – although in many cases the trauma that was caused to the whole body by crucifixion would bring about death before the legs were broken or asphyxiation caused death.

However, the Jehovah's Witnesses now claim that this is not how Christ died. In this article we will look at the evidence that they allege supports this claim and other relevant evidence.

Linguistic Evidence

The Romans crucified thousands of people, and there is abundant evidence of this means of execution. The English word 'crucifixion' comes from the Latin, the language spoken by the Romans. The Latin word 'crucifixio' means 'to fix to a cross' and it is formed from the prefix 'cruci' from the Latin word 'crux' ('cross') and the verb 'figere' ('to fix or attach'). There is not the tiniest amount of doubt concerning the meaning of these words, nor concerning the form of the cross.

The Jehovah's Witnesses base their claim mainly on one Greek word used in the New Testament: σταυρος (pronounced 'stow' [as in 'cow'] – 'ross'). They say that this means a pole or a stake. But they thus demonstrate the extreme limitations of their knowledge of Greek and of how languages work.

The famous classical Greek poet Homer lived at some point between the 12th and the 9th century BC At that point in time the word σταυρος meant a pole. But in the centuries prior to the coming of Christ the Romans conquered the Greeks. Greek continued to be the main language used in all the countries that had previously been conquered by the Greeks. But the Romans imposed their administrative structures, their civil engineering systems (roads, aqueducts, bridges, sewerage systems, etc.) and – above all – their legal system, including crucifixion as the means of administration of the death penalty.

The Greeks, who did not use crucifixion as a means of execution, had to adapt their language and find a word for this new way of implementing the death penalty. They had to do one of the three things that languages do to give names to new ideas, events and objects:

- invent a new word

- take a word from another language (frequently changing its exact meaning slightly or even greatly)

- employ an existing word, but give it a new meaning.

They decided to use a word that already existed – σταυρος – but to give it a new meaning. That is to say, 'σταυρος' became the Greek word that translated the Latin 'crux' (the noun) and 'σταυροω' was used for 'crucifixio' (the verb).

This application of an existing word to refer to a new concept is done by all languages. That is to say, languages change with time. This can be observed even in very short periods of time, and any person older than about 30 will know words whose meaning has changed during his or her lifetime.

The expert in Koiné (New Testament) Greek and in linguistics, Dr David Alan Black, college lecturer and author of numerous books on Greek, writes in his book Linguistics for Students of New Testament Greek[1] that the etymological method – which attempts to define the meaning of words on the basis of their original meaning:

used alone, cannot adequately account for the meaning of a word since meaning is continuously subject to change.… It is therefore mandatory for the New Testament student to know whether the original meaning of a word still exists at a later stage.… Hence it is not legitimate to say that the 'original' meaning of a word is its 'real' meaning.[2]

When the Jehovah's Witnesses say that σταυρος can only mean a pole or a stake (because that was its meaning some 800 or perhaps even 1200 years before Christ, 500 or more years before the Romans invented crucifixion), they are denying this fact, to which the scientists who study languages – the linguists – have given a name: the diachronic development of languages, that is to say, how languages change – and with them the meaning of words – in the course of time.

In the 21st century, the word in modern Greek for 'cross' is 'σταυρóς' – the same as it was in the first century! This does not mean 'a pole'; it means 'a CROSS'. The word for 'crucifying' is 'εσταυρομενος', the root of which is σταυρο from σταυρος. If we did not know the meaning that the Greeks give to this word, we would need to do no more than to look at any Greek church, and we would see on the top of the building, outside, a cross, not a stake!

Change of word meaning – Example 1: Shuttle

To give an example of the diachronic change of a language, let us take the English word 'shuttle'. The origins of this word go back to the mediaeval period, when it referred to the piece of wood or bone round which the thread was wrapped for use when weaving. The dictionary defines this as "the instrument that is used by weavers when weaving". The shuttle was continually pushed from left to right, and then from right to left to weave, in order to make the cloth.

In the twentieth century, in the 1960s, the word 'shuttle' was adopted in England and the United States to describe a bus that always had the same route between one point and another, without visiting other places (and with few or no stops en route), and then returning in the opposite direction– for instance, the buses that went between an airport and the nearest city.

At the end of the 1970s the North Americans developed a space vehicle that – in contrast to all space vehicles up to that point – would be reusable, and as the concept was new, they had to do what the Greeks had done more than 2,000 years earlier in the face of something completely new, and choose between the three possible options (given above). They did the same as the Greeks had done on that occasion and went for the third option: taking from their own language a word that was already a thousand years old and giving it a new meaning. They chose the word 'shuttle'. If on hearing a news report of the arrival of the 'shuttle' at the international space station, I were to insist that the Americans had sent into space a mediaeval wooden or bone shuttle for weaving, it would be ridiculous – just as ridiculous as when the Jehovah's Witnesses say that Christ was 'crucified' on a pole, because that was the meaning that the word σταυρος had had a thousand years earlier.

Change of word meaning – Example 2: mouse

To give an example of something that has become a component of the daily life of most people in England (as in the rest of the world), if someone were to speak about their computer's mouse and I were to reply, "What are you doing with a mouse in your house? How do you feed it? How do you prevent it from escaping? What do you do so that the cat doesn't eat it up?" – everyone would laugh at me, and justifiably so, because the word 'mouse' has acquired a new meaning, and this meaning now predominates so much in the majority of contexts that generally one would not even think of its original meaning, that of a small rodent.

Of course, someone could quote from recent publications in which the word 'mouse' is still used with its original meaning. (This is precisely the type of 'evidence' presented by the Jehovah's Witnesses to justify their interpretations of various words.) But the fact that this is true – as it is! – does not have as a consequence that each time that someone talks about their computer's mouse we have to say that they have an animal in their office!

To summarise:

- 'crucifixio' is a Latin word

- it means 'to fix to a cross'

- it was the Romans – not the Jews nor the Greeks – who crucified people

- languages change in the face of new experiences

- old words are frequently used with a totally new meaning

- the Greeks did this with the word σταυρος since before the time of Christ to describe the method of execution practised by the Romans, nailing the condemned person to a cross

- in the 21st century the Greek word σταυρος is still used in modern Greek with the meaning 'cross' – not 'pole'

- for more than 50 years the Jehovah's Witnesses accepted that Christ was crucified on a cross – and included illustrations of this in their publications which were distributed to millions of people around the world.

Mistranslation by the Jehovah's Witnesses

In their 'New World Translation' of the Bible, the Jehovah's Witnesses put the words 'torture stake' wherever the Greek has the word σταυρος. This even contradicts their own interlinear translation, which also incorrectly renders σταυρος as 'stake' but at least does not add the word 'torture', which is not in the original Greek text (cf. John 19:19 or other references to the cross in the New Testament).

Evidence by Opponents of Christianity

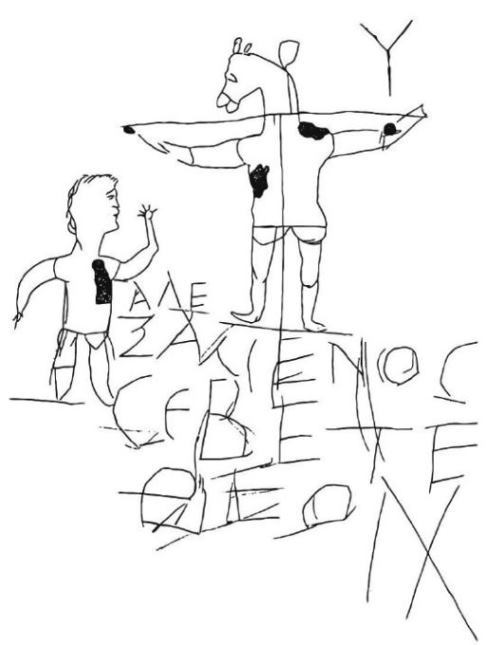

The text and image in the following section were downloaded from the Wikipedia article 'Alexamenos graffito' on 18th January13. There are also numerous published articles on this graffito by a wide range of recognised and respected academic publishers. The Wikipedia article summarises the main points of some of these publications. It has here been shortened and slightly edited without changing the meaning.

The Alexamenos graffitoWhen a building in Rome called the domus Gelotiana was unearthed on the Palatine Hill in 1857, this graffito was discovered carved in plaster on a wall. The emperor Caligula (12-41 AD) had acquired the house for the imperial palace. After Caligula died, the house was used as a Paedagogium or boarding-school for the imperial page boys. Later the street on which the house was located was walled off to give support to extensions to the buildings above, and so it remained sealed for centuries. The image depicts a human-like figure who is attached to a cross and who has the head of a donkey. To the left of the image is a young man, apparently intended to represent Alexamenos, who is raising one hand in a gesture possibly suggesting worship. Beneath the cross there is a caption written in Greek: Αλεξαμενος ϲεβετε θεον, which means "Alexamenos worships (or: worshipping) God".[3] No clear consensus has been reached as to the date in which the image was originally made. Dates ranging from the late 1st to the late 3rd century have been suggested, although the beginning of the 3rd century is thought the most likely date.  InterpretationThe inscription is accepted by authoritative sources … to be a mocking depiction of a Christian in the act of worship. Both the portrayal of Jesus as having a donkey's head and the depiction of him being crucified would have been considered insulting by contemporary Roman society. Crucifixion continued to be used as an execution method for the worst criminals until its abolition by the emperor Constantine in the 4th century. One interpretation is that the figure in the image has an ass's head to ridicule Christian beliefs. |

Thus this cartoon is possibly the earliest drawing of the crucifixion of Christ, probably completed at the beginning of the 3rd century, ie. in the early two hundreds. It shows Christ on a cross, not a pole or a 'torture stake', with his arms out-stretched to the left and the right. The fact that it was not drawn by a Christian adds to its significance as an independent indication of the nature of crucifixion and that this was the way that Christ died.

Textual Evidence

In the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, certain words considered 'sacred' were written in a special, abbreviated form, with a line above the letters. Thus, ΘΕΟC[4] ('GOD') was written:

Other words considered sacred and thus similarly abbreviated included the Greek for 'Father', 'Son', 'Spirit', 'Jesus', 'Christ', 'Lord' and 'Saviour'. Such words are usually referred to by academics with the Latin title, 'nomina sacra' (sacred names – singular: 'nomen sacrum').

Likewise, the words for 'heaven' and 'cross' were treated as nomina sacra. The Greek for 'cross', written with capital letters, is CΤΑϒΡΟC[5]. The accusative form, as in the following quotation, is CΤΑϒΡΟΝ. It was abbreviated as:[6]

Note that the first two vowels (Αϒ) are omitted and the Τ (pronounced 'Tau') is super-imposed on the Ρ (pronounced 'Rho'), to create the shape of a cross, with the vertical line of the Rho extending above the horizontal bar of the Tau. Furthermore, the curved section of the Rho symbolises the head of Christ. The horizontal line above the word shows that this is a 'nomen sacrum'. The nomen sacrum for the cross is technically referred to as a 'staurogram'. The staurogram occurs consistently as a standard abbreviation for the word 'cross' in the earliest Greek manuscripts of the New Testament and is a visual confirmation of the shape of the cross on which Christ was crucified.

These manuscripts pre-date any artwork and are even older than the Alexamenos graffito referred to above. For example, manuscript P66, which contains the staurogram, is dated at "prior to 150 AD."[7] As P66 is believed to be a copy of an original manuscript, we have evidence that with an extremely high level of probability goes back to the first century.[8] Another manuscript, P75, is dated at "late second century"[9], ie. approximately 175-190 AD. In any case, the scribes who produced P66, P75 and other early manuscripts were living in a time when crucifixions were still being carried out, and so the shape of the cross was well known to them.

The staurogram provides remarkably strong evidence that the cross on which Christ was crucified had the shape that has been accepted throughout the whole of the past two thousand years by Christians and non-Christians alike – indeed, by virtually everyone except the Jehovah's Witnesses, who also previously accepted this.

Additional Evidence

There is moreover an enormous amount of additional evidence. To mention only some examples:

- There are numerous descriptions of crucifixions in antiquity

- There are images of crucifixions carved into rocks of the same period

- There is archaeological evidence. For instance, nails have been found that not only attached the condemned person to the cross, but also fixed the horizontal beam to the upper part of the vertical one

- The cross was adopted as a symbol by Christians from at least the beginning of the second century (ie. about the year 100) by believers who had been taught first-hand by eyewitnesses of the crucifixion.

These are irrefutable historical facts. To reject all this evidence – in consequence, moreover, of a lack of understanding of the Greek in which the New Testament was written – is completely impossible to justify.

Evidence Presented by the Jehovah's Witnesses

As additional evidence, the Jehovah's Witnesses point[10] to the existence of an engraving by Justus Lipsius in which Christ appears nailed to a post. This 'evidence' deserves comment.

- The Jehovah's Witnesses do not say when Lipsius lived nor do they give a date to the engraving.[11] In fact, Lipsius lived from 1547 to 1606. Thus this engraving was made more than a fifteen hundred years after the crucifixion of Christ.

- The Romans had stopped using crucifixion in the year 337, so the artist did not have contemporary evidence of how it was carried out.

- In consequence, his picture came from his own imagination.

- This therefore does no more than demonstrate that the artist had made the same mistake as that made, five hundred years later, by the Jehovah's Witnesses.

- When they refer to this engraving, the Jehovah's Witnesses are using the same tactic that is used by them when they quote from just one or two translations that seem to give support to their translation of some word or phrase in the Bible – but then do not quote from the other 3,000 translations that contradict them.

- If one painting is valid evidence in support of their claim, by the same argument the thousands of sketches, paintings, sculptures and other representations in iron, wood, stone, tapestry and vestments with illustrations woven or embroidered into them – as well as other objects, some of them almost 2,000 years old – must also be valid evidence contradicting their claim.

Biblical Evidence

The reader will perhaps have noticed that all of this information has been presented without any need to quote from the Bible. This is because we do not depend on the Bible to understand what crucifixion was. Nevertheless – as one would expect – the Bible also supports what we have said.

The crucifixion of Christ is the most dramatic part of the New Testament. It is described in all four gospels. 'The cross' is one of the main concepts of the New Testament, both in the preaching (which is seen in the book of Acts) and in the letters that occupy most of the rest of the New Testament.[12] The Greek of the New Testament uses – of course! – the Greek word for 'cross' – 'σταυρος'. But as the Jehovah's Witnesses insist that this word has only the meaning that it had had 800 or a thousand years earlier, these references are of no use to us. It is necessary to know the meaning that speakers of Greek had given to this word since already 300 years before Christ, and this has been amply demonstrated above.[13]

Christ's stretched-out hands

The Bible does not waste time giving a definition of 'crucifixion' – any more than it does of any other word (for instance, 'horse', 'king', 'house', 'to eat' or any other object or event). After all, it is not a dictionary. But it uses words whose meaning was well understood by its readers and hearers. Nevertheless, when Christ explained to Peter that when he was older he, too, would be crucified, he said, "you will stretch out your hands" (John 21:18) – thus giving a description of the posture in which He Himself had been crucified a few days earlier – with his hands stretched out, one to the left and the other to the right, on a cross.

The nails in Christ's hands

In contradiction to what they published for years, now Jehovah's Witnesses publish pictures in which they show Jesus' two hands together straight above his head, with one long nail driven first through one hand and then through the other hand, which is underneath it. Yet this use of one nail is contradicted by the words of Scripture. In John 20:25 we read the words of the Apostle Thomas: "Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe it." Thomas is only talking about Jesus' hands, not about His feet. The word 'nails' and the verb 'were' are both unambiguously plural. In fact, in the original Greek the word 'nails' is in the plural twice, ie. there were two nails, one in each hand, because the hands were not placed one on top of each other above Christ's head, as the Jehovah's Witnesses now claim, but stretched out, one on each side of him, with one nail through each hand or wrist, not on a vertical stake but on a cross.

The shape of the Cross

The crosses for crucifixions were not manufactured in a factory, and did not all have the same dimensions. The cross bar was attached to the vertical beam once the condemned person had arrived at the place where he was about to be crucified. In consequence of this, when the cross bar was placed higher up, sometimes the two beams formed the shape of a letter 'T'. However, we know that in the crucifixion of Christ this was not the case – because the notice written by Pontius Pilate was nailed above Christ's head (Matthew 27:37, Luke 23:38) – exactly the same as in the illustration in the book The Harp of God, which was published by the Jehovah's Witnesses themselves, but which they now reject!

References:

[1] David Alan Black Linguistics for Students of New Testament Greek Baker Books, Grand Rapids, 1988, 1995.

[2] Ibid., p.122.

[3] In passing, it is worth noting that the opponent(s) of Christianity who produced this image and the caption under it understood Christians as worshipping Christ as God.

[4] Note that at that time the Greek capital letter 'Sigma' was written C, Σ being a later form of the letter.

[5] Closest approximation with the symbols available for this article.The font used here depicts the shape of the Greek letters used in the early manuscript P39, a manuscript of the Gospel of John written on papyrus and dated at the third century (ie. the two hundreds AD). In different manuscripts there are naturally minor variations in style and sizing of letters, depending on the handwriting of the scribe. [Editor's note: the author's original PDF of this article gives a better representation of these symbols than that shown above.]

[6] Illustration from Thomas A. Howe Bias in New Testament Translations? Charlotte, NC: Solomons Razor Publishing, 2010.

[7] See Philip Comfort Encountering the Manuscripts Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2005, p.117.

[8] Comfort indicates that the use of the principal nomina sacra (including the staurogram) may go back to the original manuscripts (the 'autographs'), op.cit., p.202.

[9] Comfort op.cit., p.72.

[10] Appendix to The Kingdom Interlinear Translation of the Greek Scriptures, published by the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, Brooklyn, New York, 1969, p.1156.

[11] The Kingdom Interlinear Translation of the Greek Scriptures, p.1156.

[12] The other main concepts are: 1) Jesus is the Christ, the promised Messiah; 2) He died for our sins (on a cross!); 3) He rose from the dead; 4) to be saved, we must repent and put our faith in Him. It would be possible to give an extremely large number of Bible references that indicate this, but I shall not do so, as that is not the focus of this article.

[13] Amongst the many experts in the Koiné Greek of the New Testament from whom we could quote, without any doubt the greatest authority is A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian Literature by Bauer, Danker and others, published by the University of Chicago Press, 2000. This work quotes from Greek authors from the time of Homer to the first centuries of the Christian era, giving both the meanings that words had had at the time of Homer as well as the meanings that they acquired after the Roman conquest. This states that 'cross' was the meaning of the word σταυρος in New Testament times. (p.941).

© 2013, 2014 Trevor R. Allin

Initial version 2nd March 2013. Revised 17th July 2014.