What Does it Mean to be Human?

Paul Coulter begins his extensive study of what it means to be human. In this first chapter, he lays out some of the difficulties in tackling the question.

When I was first asked to speak (and by extension write) on the question of what it means to be human, I must confess to a considerable degree of apprehension for two reasons:

a) A concern over the limits of my knowledge

b) A concern over the impossibility of objectivity

A Concern About My Limitations

The first concern is because there are so many different angles from which the question could be considered, and I do not regard myself to be an expert in any of them. Furthermore, there is a strong likelihood that some readers of this article will be much more expert in some of these fields than I am. Consider, for example, the different angles from which the following people could approach the question:

- A lawyer may be concerned about legal definitions of rights and responsibility (culpability)

- A doctor will consider her duty to respect, preserve and enhance human life

- A theologian will wonder about mankind’s relationship to God and religious theory

- A philosopher will wrestle with the purpose of human life

- A sociologist will consider human beings in relationship to one another in families and societies

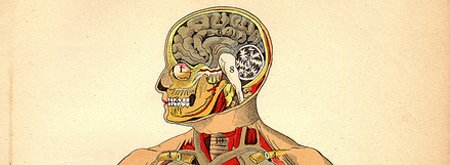

- Anatomists, biochemists and physiologists will consider the structure and function of the human body

- An anthropologist may study culture, artefacts, language and biology to understand humanity

- A computer scientist may wonder at how artificial intelligence approximates to the human mind

- A historian will look for lessons from human history as to what motivates us and shapes our identity

- A political theorist will ask how human societies and nations can best be governed

I do not seek to hide the limitations of my knowledge, but rather to acknowledge them so as to avoid creating a false expectation for you, the reader. I have dabbled in the practical outworkings of several of these disciplines, but it is as an interested amateur that I approach most, and hence this article is heavily dependent on the expertise of others. I shall attempt to acknowledge my dependence as I write by referencing quotations and concepts.

A Concern about Objectivity

Any answer to this question is bound to be highly subjective and shaped by experience. Being human will mean many different things to different human beings. When asked, “What does it mean to be human?”, I am tempted to respond, “Which human?”, for it seems to me that each human life is a unique story lived out in a specific time, place, culture and context. Your understanding of what it means for you to be human may be radically different from mine because our experiences, personality and culture may be different. Even if you have the great misfortune to share my personality type (I would love to tell you what it is, but the longer I live the more confused I am about that), and assuming you have had experiences approximating to mine (two parents, three grandparents, one older sister, pet Labrador as a child, stable home, great opportunities, good education, cross-cultural marriage, encounters with certain illnesses, experience of evangelical Christianity etc. etc.) you may still be a very different person from me, and may understand and experience your life and the world in which it is played out quite differently than I do mine. Most obviously, slightly more than half of all humans in the world are female, and I can claim no experience whatsoever of what it means to be a human of the female variety! Although I express my limited ability to describe the subjective experience of being human in universal terms as a potential weakness in my writing, I am at no greater disadvantage than the writers I will quote in this respect. In fact, this issue does raise certain other questions that are pertinent to our enquiry. Exactly what is it that makes me different from you? Is it the differences between our genes, differences of environment, culture and upbringing, or a mixture of the two? The debate about nature and nurture is an important aspect of what it means to be human. In addition, what is it that makes connection between two individuals possible? Although we cannot ever claim to fully understand another person’s situation or perspective, we are capable of 'putting ourselves in their shoes'. We can imagine their feelings and listen to their verbalisations of their experience. Where do these faculties of consciousness and empathy arise from?

Suffice to say at this point that I am aware of the impossibility of objectivity in tackling this question and that I apologise in advance if what I say does not make sense because your perspective is different from mine. I proceed, however, in the belief that the interchange of ideas is possible and that there is an ultimate truth about reality to which we can aspire to move together in our understanding. My concern in this article is not to try to explain the subjective experience of individuals (there is, I feel, a danger that discussions of this kind focus either on the extremely gifted or those whose lives are most severely disabled) but to consider humanity as a whole. We stand or fall together, and we belong together – from the greatest to the least.

My 'Qualifications'

Having acknowledged my concerns, I suppose I must now provide some kind of justification for why I decided to accept the challenge of writing on this subject. Although my lack of expertise is in one sense a disadvantage, I hope in another sense that it might be an advantage as I attempt to distill key ideas from the writings of experts and make them accessible to my fellow non-experts. Trying to explain what you have learnt to another person is always a great way to clarify your own opinion and to test your own comprehension of the subject. In addition to this potentially selfish reason for writing, I genuinely hope that what I write might be of some benefit to you. In preparing for this article I was forced to read a number of books that had previously languished on my shelves and to purchase a few others I had known previously only by reputation. Having spent a considerable number of hours reading and researching I have found what I have read both helpful and provocative. It is my desire that in reading this article you too will be provoked and helped.

I have had involvement in a number of areas of life in which the question of human identity is important. I have worked as a medical doctor and as a lay magistrate. I have been engaged in pastoral ministry both within my own culture and cross-culturally and have lectured in a theological college. I have studied genetics and ethics. I have a keen personal interest in history. However, it is to none of these areas that I appeal for my basic qualification to speak about human nature. My only legitimate qualification, I feel, is that I am (at least as far as I can tell) human. I speak to 'us' about 'us' as one of 'us'. Not only am I human, but, strangely enough, my parents, and indeed my entire extended family were also human. I have lived in human society all my life and have often needed to draw upon my understanding of human nature to explain and interpret the actions of other humans I have encountered. When I sought a mate it seemed instinctual to me to seek a human as my partner. Lo and behold, the offspring of that union also turned out to be human. It seems that I am surrounded by human beings and that it is amongst them that I feel both most at home and most uneasy. At home because I can see my own feelings, thoughts, fears, and hopes lived out in their lives, and that makes connection possible. I crave their love and I find some pleasure in offering love to some of them. Uneasy because in them I see not only my own goodness but my own twistedness – my selfishness, weakness, greed and impurity. In interacting with them these aspects of my being are frequently exposed. They have a unique ability to anger me, and the possibility that they may reject me disturbs me in a way that little else can. Even the fear of death at times seems paltry when compared to the fear of loneliness. At times I have wished as I have read the writings of others that they would also own up to these most obvious facts. I have wondered how some could write so dispassionately and some could analyse the flaws in the thinking of others with such apparent confidence that their thinking (perhaps uniquely) is free from the same kind of flaws. In short, I found myself wishing for a little humility. I hope that I can reflect that quality in my own writing, and if I do not then I beg your forgiveness and patience.

Go to 2. Why ask the question?

© 2010 Paul B Coulter

This article is reproduced here by the kind permission of the author.