A Long Way East of Eden

A Long Way East of Eden: Could God explain the mess we're in? examines the significance of the ‘God-question' and the impact of atheism – the loss of God in a culture.

What implications might emerge – how might we understand what's gone wrong around us – if we spent forty-five minutes on a train meditating on the Bible's opening sentence:

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth...?

Genesis' primal narratives offer a radical diagnosis of our alienation: that our conscious turn from God, our enthronement of our autonomous ego in an unworkable independence, has led in steady, logical progression towards cultural collapse.

'The ice that still supports people today has become very thin; the wind that brings the thaw is blowing', wrote Nietzsche in The Gay Science. We sense the foundations shifting beneath our feet, and we know we haven't seen the end of the process yet. Indeed, we feel an existential 'black hole' at the heart of the west; an absence lies at the very centre of postmodernity. Who am 'I'? Do 'I' still have value? Is there any real point to life? How can 'I' know what's right and wrong, and what will it mean if 'I' can’t? Is love a reality? Can we ever know truth? Is there any reason for hope? We've reviewed these issues and others that flow from them, and seen how often they seem triggered by a common factor; that at the heart of the maelstrom of our time there stands an Emptiness, a 'space in the shape of God' (Pascal).

In short the God-question matters, matters enormously. But how could we know whether there really is a God who could make meaning in our world?

...how could we know whether there really is a God who could make meaning in our world?

This book cannot give a full answer to that question. Firstly, because it hasn't set out (and doesn't have space) to survey adequately the evidence underlying historic Christian hope.[1] But secondly, because rediscovering God doesn't work that way. At least according to the Bible, rediscovering God isn't like discovering whether a particular subatomic particle exists. Rather, it is like learning to know, and love, a person. Above all it is relational.

Unlocking the Skylight

To say that raises two immediate issues.

First, if knowing God is personal and relational, then the truth about him / her / it will be 'revealed' to us in a manner appropriate to – designed for – us, and not for anyone else.

Second, if we want to give real consideration to biblical-Christian faith, we must take seriously what it really says. This includes recognizing that we don't approach potential relationship with God from some ideal, objective starting-point. Rather, as we saw last chapter, if biblical faith is true, then we start from a condition of deep alienation from God. That could imply a major problem with our ever being able to learn the truth.

Let's consider this second issue first. 'You know I can't make it by myself', sang Bob Dylan on Slow Train Coming, the first album of his 'Christian' phase, 'I'm a little too blind to see'. Our entire 'modern', post-Enlightenment tradition revolts viscerally against that idea; progress‑oriented western man has had enormous (and not unjustified) confidence in his investigative powers. We've been deeply committed to the faith that, in the end, we can observe and reason our way to the truth about anything whatsoever. As the last century drew to a close, however, we became less sure of ourselves. Postmodernism may be a little more humble; certainly it is far less triumphalistic about the omnipotence of our (western) reason. And according to Jesus, we do have a real problem.

'Why is my language not clear to you?', Jesus asked the Jews, and answered his own question immediately: 'Because you are unable to hear what I say'.[2] Two chapters earlier he was even more blunt: nobody could know the truth about him, he declared, 'unless the Father who sent me draws him'.[3] St Paul was equally 'unmodern' (or maybe post-modern?): ordinarily, he declared, we human beings are 'blinded', so that we are simply unable to perceive the realities of the issues involved;[4] by nature we 'cannot understand them'.[5] There's a fundamental problem with our presuppositions, our paradigms, that goes deeper than the intellect. We 'deliberately forget' spiritual realities, says St Peter.[6] This possibility is hard on our pride. Unfortunately, we cannot rule it out: if God says he cannot be known by our unaided research, it might just be true.

To repeat: for Christian faith, knowing God is personal. The biblical hypothesis presents us as needing direct, individual revelation from God if we are to know the truth, on a par with the 'Word' that set the entire creative process in motion. This comparison is St Paul's: 'God, who said, "Let light shine out of darkness," made his light shine in our hearts to give us the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ'.[7] What's in view here is not an irrational or even (necessarily) mystical experience. Rather, Paul affirms that our hearts have a built-in prejudice, such that God's enabling power is indispensable if we are to see clearly the real, objective facts. It is in 'the face of Christ' that we can hope to see the glory of God; but we need God's light to grasp and evaluate aright what we are seeing.[8] But that moves us from mere assessment of data to the challenge of relationship with a Person.

Two further points follow. First, the New Testament itself guarantees that the truly honest seeker will not be disappointed. Jesus' teaching presents a God who comes out like a shepherd looking for us as we are wandering in the dark: 'Seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you'.[9] Second, however, we know that establishing a meaningful relationship with any person depends on our approaching them in a respectful and appropriate way. So it will be in this case. We are not now indulging in an intellectual game, or conducting a casual experiment in a test-tube. Rather, we are exploring, opening ourselves to, the possibility that we have a Maker (even an Owner); a Father who we need to speak to us, to show us reality.

Perhaps no such being exists. But if he does, we approach him as members of a rebelled race, and as individuals who have chosen repeatedly to drive his presence to the periphery of our consciousness, to live as though he were unimportant. So as we come to him asking for 'grace', for his revelation of ultimate reality, we must be willing to face up (if he speaks) to his rights over us. And that's hard. Some thinkers suggest we live at 'the end of the secular century'; but while we may warm to the thought of a heavenly Santa Claus or 'figure of light' to protect us and welcome us after death, we're often profoundly anxious that there should not be a God who we might need to obey; or still worse, who might assess what we've done with our (and his) environment, and to each other. Many of us have a built-in anxiety that such a God should not exist.

But we have to face the issue. In fact it is not necessary to believe that God exists before starting to treat him as God. Even the thoroughgoing agnostic can pray (if there is no God, it is only a minute lost): 'God, I do not know if you exist. Nor do I know if I can find out on my own. But I realize that, if you do, I may be entirely dependent on you showing your truth to me. Therefore: if you show me your truth and your ways, I vow that I will give myself to you, and start to follow you wherever you lead'.[10]

Does this not jeopardise our exploration by assuming its conclusion at the very start? Not really (though even if it did, we would only be following the rules of scientific method – presuppose the hypothesis and see if it matches up with what happens). Such a prayer says merely, 'God, if you are there, if you are all that Jesus taught, then I will follow you'. But it also offers us a step forward in self-knowledge. It's striking how many of us feel profound reluctance to pray in these terms – and our reaction reveals our hearts;[11] it helps us see whether our beliefs are controlled by deep-seated determination to preserve our independence. If that is so, there is not much point (yet) in looking at the evidence; we're maintaining a position from which, even if God is real, we will most probably never know, at least in this life. Rather, the question will be just why we feel so anxious to preserve our exile from God's presence.[12]

Such a prayer leads us beyond the safely cerebral. Logically, we would no more expect to meet the living God just through reading books than to meet a partner just through reading Mills and Boon. Sometime, something has to be done, the risk has to be taken. To pray such a prayer is to step outside what's been called the 'Cartesian madness of the West', the absurdity of thought in a bloodless vacuum. It is to set our total being as the stake of our gamble with the unknown. It is the only appropriate way to attempt an approach to the Creator who may perhaps be there. If there is no God, we shall ultimately prove to have wasted a little of our time: no great loss. If there is a God, we shall have opened the door for heaven to break in on our experience.[13]

Understanding Faith

What then do we expect? We expect a journey: a journey into faith. And immediately that word presents a stumbling-block. 'It's nice for those who "have" faith; I wouldn't even mind it myself; but you can't "work it up", can you?' Or: 'How can any intelligent person tolerate living on the basis of faith?'

Normal life depends on our willingness to take a thousand steps of faith each day, in our memory, our perceptions, our reason, ...

But life is not so simple. In postmodernity it has become increasingly challenging to believe that we 'know the objective truth' about anything; how could one dare believe that one knows? 'The just live by faith', says the New Testament repeatedly, but there is a sense in which no one lives by anything else. It is absurd to say we refuse, or are unable, to live by faith. 'Absolute' proof never existed for anything, even our own existence. Descartes tried to prove the latter with his famous 'I think therefore I am'. But all that can be proven from 'There are thoughts' (not 'I think', which smuggles in the 'I' it is trying to prove), is precisely that and no more; 'There are thoughts' or 'Thinking is happening'. What, if anything, is doing the thinking – whether it has any lasting identity, whether it is an octopus dreaming it is human – is in no way 'proven'. (Is our "reality" any more than 'an illusion caused by lack of alcohol'? Probably; but the point cannot be proven!)

We live by reasonable faith. Every time I catch a bus home I make a whole series of acts of faith. Faith in my memory of the link between that bus' destination and where I live; faith in the driver's intention to go where his company promised; faith in my perception that he probably isn't drunk; faith that the bus is properly maintained. I cannot prove these absolutely, but there is enough real evidence to justify my steps of faith. When I pause at the corner shop to buy 'fresh' fruit, it is an act of faith in the shopkeeper. When I greet my wife, I am building confidently on faith in her – and thus faith in my judgment, faith indeed in my memories on which that judgment is based – that she is not secretly sleeping with the neighbour and plotting to poison me. Normal life depends on our willingness to take a thousand steps of faith each day, in our memory, our perceptions, our reason, and the judgment and good intentions of others (to say nothing of our dress sense and our deodorant!) The world might be very different from the way we perceive it; we will have to live by faith in the evidence that it isn't. Only a paranoid would refuse to eat breakfast because of the impossibility of proving beyond all doubt that no burglar has poisoned his egg; but the possibility cannot rationally be ruled out, and faith is indispensable for breakfast.

There is no way of living except by faith: faith, not set against reason, but defined as stepping forward in a trust based on reasonably solid grounds, even though they amount to less than absolute proof.[14] And this, of course, is good scientific method:[15] to take a theory and then test it by its internal consistency and by how far, longterm, it integrates and matches the data we receive. In one sense such an approach (to life or science) remains a gamble of faith. But some hypotheses about the world come to make far more sense than others; and these we live by. So Christian faith, writes Colin Brown, is a 'hypothesis that … makes sense as we go along living it'.[16] Jesus said something similar in John 7:17; and his challenge to his first disciples fits the need too of a postmodern culture: 'Come and you will see'.[17]

Ways of Seeing

Suppose, then, that we are willing to embark on this journey of personal exploration. We want to give consideration to the Christian hypothesis; and we've chosen (it is an act of our inmost, fundamental will) to let God be God in our lives if he should exist. What then?

For many people in the two-thirds world these may seem stupid questions: anyone with a mind and heart knows there is a God. It is not easy to find atheists in, say, Iraq or Brazil or Nigeria. I remember a woman I deeply respected asking me – at a time when I very much doubted God's reality – 'But don't you just know he is there?' Such a condition is uncommon in the west. (Though not unknown: the great psychologist Jung told a BBC interviewer shortly before his death, 'Suddenly I understood that God was, for me at least, one of the most certain and immediate experiences... I do not believe; I know. I know'.[18]) I was willing to concede it might be a 'normal' condition for humanity, to which our western culture, its perceptions overwhelmed by the media-dream-worlds it has created, has blinded and deafened itself. But I had to say to my friend: No, I don't 'just know'.[19] Many others of us are the same. What do we do? Where might we explore (or be given) the basis for living by faith?

As we've noted, to Christian belief the knowledge of God is something deeply personal. There are many different areas which God may select to make us, as individuals, aware of his reality: the 'keys' to our particular 'lock'. For some it may be personal experience of God's presence, in the miraculous or in answered prayer – either in our own lives, or in the life of someone we know well enough to trust.[20] For others, it may be experience of the meaningfulness of Christ helping someone we know to endure and even grow despite immersion in horrendous suffering. For many it may be the Bible: our experience of being 'spoken to' as we read it or hear it preached, our sense of its profundity, relevance and coherence [21] – our sense, as Peter said to Jesus, that these are 'the words of eternal life'.[22]

For yet others, what we love most may begin to 'turn the key'. The first 'intuition of God' may come through experiencing childbirth ('Searching for a little bit of God's mercy / I found living proof', wrote Bruce Springsteen after the birth of his first child). Jewish novelist Saul Bellow, writing about Mozart, said that 'At the heart of my confession, therefore, is the hunch that with beings such as Mozart we are forced to speculate about transcendence, and this makes us very uncomfortable'. George Steiner argues at length in Real Presences that the experience of great art only makes sense if it is underpinned by the reality of a God. Television naturalist David Bellamy wrote that his 'road to Damascus was the wonder of the natural world'.[23] To the Christian, such intuitions are actually the revelation of God, to be stewarded with care. 'Take heed how you hear', said Jesus; the intuition of grace may not return, and we are responsible for what we do with it.[24]

Or it may be other considerations. It is hard to 'take God seriously' when the media don't; yet where does the majority opinion really lie? Don't our North Atlantic fashions of materialistic thought seem myopic when set in a wider context of history or geography?[25] The vast majority of the human race has always believed in a supernatural universe including a supreme God, so far as we can tell; and the majority certainly still does. 'The main issue is agreed among all men of all nations', said the Roman writer Cicero, 'inasmuch as all have engraved in their minds an innate belief that the gods exist'.[26] In the next generation, Seneca argued similarly that no race had departed so far from the laws and customs that it did not believe in some kind of gods.[27] Calvin concurred, fourteen hundred years later: 'There is, as the eminent pagan says, no nation so barbarous, no people so savage, that they have not a deep-seated conviction that there is a God'.[28] And without doubt, the Christian church in particular has grown faster across the continents in the last century than in any previous one.[29] Of course we westerners tend to think of ourselves as 'humanity come of age', and assume that because we control the world's media and educational systems our de-supernaturalised worldview must be the whole truth.[30] But humility might urge us to note the near-universality of belief elsewhere, and to wonder if the majority of humankind isn't sensing something we have grown deaf to. Shall I stake my life on the probability that they are right, or that they are wrong?

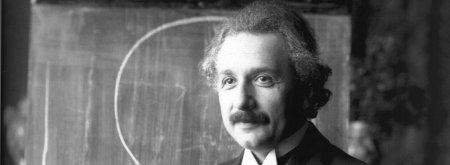

The universe we inhabit poses further questions. If there is no God, we must somehow conceive the cosmos as just 'sitting there', as it were, expanding and contracting perhaps, but in existence for no imaginable reason. Sartre's comment about the oddity of there being something rather than nothing has some force. And that 'something' includes the physical laws; the universe we live in is in many ways a stable place – we might say a curiously reasonable place. The pattern of laws and constants that enables its existence in so rational and unchanging a manner might seem suggestive of a Law-maker.[31] 'The mind refuses to look at this universe being what it is without being designed', said Darwin late in his life; Einstein remarked that the most incomprehensible thing about the universe was that it was comprehensible, and that he was glimpsing the handiwork of an 'illimitable superior spirit' in what he perceived of the universe.

One fascinating recent development in science is the rise of Intelligent Design Theory. It argues that several branches of science now have well-defined procedures for distinguishing designed activity from chance phenomena. (For example, the study of artificial intelligence; forensic science; archaeology; and the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. All these fields need criteria for separating chance activity from what is intelligently designed.) By the criteria of these fields, various factors, particularly the issue of information-origin and the high level of 'irreducible complexity' in the universe, reveal clear signs of design.[32]

Such a notion is heresy, of course, running head on into prejudices built into at least a century of 'modern' culture (though by our philosophy rather than our science). Hence, these thinkers are seeking to avoid getting embroiled in the old debates about creationism; and the question of how, or by whom, these features were designed is being avoided, so that the central issue can be faced. But obviously if we come to see ourselves as the products of intelligent design, not chance, it will produce a radical change in our cultural consciousness. Inevitably, it raises questions about God.

More recently, the debates over the 'anthropic principle' have suggested that the ratios and constants of the fundamental forces in the universe – from the subatomic to the astronomical – are incredibly finely balanced. Indeed they are balanced far too precisely to be the result of anything but intelligent design, since the margin of error was minimal (one part in a million in some cases) if a universe was to emerge that could contain intelligent life. 'It is hard to resist the impression that the present structure of the universe, apparently so sensitive to minor alterations in the numbers, has been rather carefully thought out', summarizes theoretical physicist Paul Davies in God and the New Physics. '…The seemingly miraculous concurrence of numerical values that nature has assigned to her fundamental constants must remain the most compelling evidence for an element of cosmic design'.[33] Cosmologist Fred Hoyle concurs: 'I do not believe that any scientist who examined the evidence would fail to draw the inference that the laws of nuclear physics have been deliberately designed'.[34] Do we not sense a Maker behind these astonishingly productive principles that have brought such complexities out of almost nothing in this strange, pulsating cosmos? Alongside this sense stand our intuitions of wonder: whether at the majesty of the galaxies, the glory and multitudinous living complexity of the natural world that has exploded out from the Big Bang, or the beauty of a sunset, a mountain-range, a stallion, a human baby. Are those intuitions sentimentality, or apprehensions of a real Designer at work? As we gaze thankfully at our world, from the sparrow to the panther to the human eye, it can be hard to avoid seeing it as the work of a personal Creator.

Or there are the issues we have considered in earlier chapters. 'Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the oftener and more steadily they are reflected on', wrote Kant; 'the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me'.[35] The singer of Psalm 19 reflects on the same combination: the 'heavens declare the glory of God', he says, and the internal 'law of the Lord' presents an equally life-giving stimulus, 'reviving the soul … giving light to the eyes'. Culturally and individually, we too sense profound intuitions of that 'moral law' – intuitions of the reality of good and evil, the truth of love and beauty, the reality and value of the individual, the trustworthiness of reason. Yet, as we have seen, these intuitions have grown discredited as they lost their grounding in God.

So were they idealistic sentimentalities, or apprehensions of genuine truth? Is there indeed no intrinsic value for the individual, no reality in love beyond lust and tactical alliance, and ultimately no ethics beyond our personal preferences? Or maybe there is a God? 'Although man may say that he is no more than a machine, his whole life denies it', writes Francis Schaeffer. In our profound experiences of love, beauty or justice we touch, not God indeed, but objective realities that only make sense in terms of God.[36] The Triune God would be a 'meaning-maker' whose truth makes sense of our profoundest hopes and intuitions – that people do matter, that egoism and cruelty are wrong, that love is real. We're trained into worldviews that negate these intuitions; yet still our hearts warn us that those atheistic worldviews are dehumanized, arid, inadequate. Maybe we should listen; maybe our hearts were trustworthy all along.

'… the face behind the universe, which now and then emerges through our subconscious mind… Nietzsche described a "sea-sickness, as we go our troubled way without outside help through the world". Sartre wrote on the subject of man and called his book Nausea. But perhaps in such moments we might have a more profound intuition and call it, with Helmut Thielicke, "homesickness"… that ache that occurs when we are alone on a mountain; or when the sun sets and we want to worship and don't know what to worship… We know there is a Face behind the universe trying to get through again… We have lost the Face that is behind everything, and so we too are becoming faceless…'

Roger Forster [37]

Seeing Jesus

Yet these issues may be too impersonal. We need to explore what happened in Palestine two thousand years ago.

First, let's consider the issue of the resurrection which the Bible presents as the final basis for our hope, the ultimate 'sign' of the supernatural's eruption into our world.[38] It's worth thinking about the body of the dead Christ. Everybody involved in the original events – friends or foes of Jesus – agreed that Christ was crucified, died, and was buried. We have the arguments of some of Christ's opponents, and know the line they followed. That he genuinely died also seems clear from the details in the records that might not have been meaningful then but become proof of death to our more developed medical knowledge.[39]

That the body then vanished, and that this was not his enemies' doing, also seems definite. Then and later, Jews and Romans wanted to remove this threat to peace and orthodoxy. Religious factors aside, the authorities had good reason for fear, with thousands of Jews turning to Christ, either that they would be called to fatal account for 'this man's blood', or that the social instability would provoke a Roman takeover and the end of the Jewish nation.[40] If there was any way his enemies could have produced the body (or those who removed it) in the early days of the infant church's rapid growth, they would surely have silenced the teaching of the resurrection; but it never happened. Rather, the early church's enemies explained the body's absence by accusing the Christians of stealing it.[41] But it is noticeable, and remarkable, that the accusation never resulted in a trial. The disciples would have had nothing to gain by such an action. Yet with no motivation, they proceeded to centre their whole lives around their affirmation of the resurrection. Equally bizarre – as we expose ourselves to the ethical teaching of these earliest Christian leaders – is the notion that, underneath, they were some of the world's most effective con-men. Strangest of all is that as many of them (and their families) were beheaded, crucified upside down, whipped and otherwise tortured or executed, no-one ever admitted the truth, that they had stolen the body. Nonetheless, if we would deny the resurrection, something like this is what we have to believe.

We can go further, however. Christ was seen after the resurrection. The careful historian Luke describes these appearances as 'many convincing proofs' (Acts 1:3). In the mid-50s AD, Paul writes to the people of the merchant port of Corinth, giving them a long list of living witnesses in Israel who had seen the risen Christ. This is very solid historical data.[42] We should consider James, Jesus' brother, a sceptic throughout Christ's lifetime; he encountered Christ after the resurrection, and was of sufficient moral stature to be accepted as leader by the thousands of believers in Jerusalem, finally being beheaded in AD 62. He, we must affirm, lied or was deceived. We should consider the meeting between the disciples and the risen Christ, recorded as the finale of both Luke's and John's gospels (these documents for the contents of which so many Christians would soon die), and again at the beginning of Acts.

What are we to make of these appearances? We cannot think of legends arising in so short a time. Besides, as C.S. Lewis points out, they would be exceedingly odd legends by the standards of classical culture. There is no account of the resurrection itself (the later apocryphal gospels certainly make up for that), no appearance to his enemies, appearances first to women. Indeed, many people find the vivid realism of passages like John 20 and 21 and Luke 24 enough to authenticate them as definitive eye-witness accounts.

Are we to see the appearances as deliberate lies? When these men were engaged in giving the world some of its highest ethical teaching? Again, we are left with the spectacle of the disciples spending their lives building a new religion whose central practices focused on the resurrection (at the same time jeopardising their eternal futures by abandoning their own religious background[43]), and finally dying unpleasantly, knowing it's all a lie. That seems highly improbable. But it is equally hard to believe these encounters were mere 'visions';[44] we note the authors' repeated emphasis on the disciples touching the risen Christ (Luke 24:38-39, Matthew 28:9, John 20:24-28), going for extended walks with him (Luke 24:13-32, 50, John 21:20), and especially 'eating and drinking' with him (Luke 24:30,43, John 21:9-14, Acts 1:4, 10:41). Hallucinations don't eat fish, and they don't go with groups of people on long country walks.

So what transformed the twelve from a group of dispirited disciples who abandoned or betrayed their Lord (an account so detrimental to the church leadership that it's unlikely to have been fabricated), into men who turned the world upside down? What transformed Paul from persecutor to missionary? What, after Jesus' death, suddenly turned his own brother James into his follower, so that he too became a martyr? How much evidence, what kind of appearances, would we ourselves demand before staking our lives and deaths in that way? The disciples asserted that the key factor was their unmistakable encounter with the risen Christ. It is not easy to see any credible alternative.

The Crux

But for myself, though there have been many other factors, the issues have finally centred on Jesus.[45] And logically, if we want to explore encounter with God-in-Christ, we will begin to read the Gospels, the four biographies of Jesus.

Here, as with the resurrection data, we don't need to begin by believing that the biblical texts are infallible.[46] To assess Christ's claims about himself, we need simply consider the records of his teaching as generally trustworthy documents. In taking this position, we are considering factors such as the wealth of documents (and the absence of radical divergences within them) that assures us we have a fairly reliable text.[47] There is the fact that these documents were written close to the events, in a culture marked by retentive memory and when many witnesses of the events would still be alive to challenge falsifications; and written by people, and in a community, whose moral rectitude seems a historically accepted fact, even among their enemies. There is the repeated stress on eye-witness testimony that we find in, say, John 19:35 and 21:24, 1 John 1:1-3, 2 Peter 1:16 or Acts 1:21-22 or 10:39-41. There is the careful historical approach displayed by the author of Luke ('Since I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning, it seemed good also to me to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught'[48]). Papias tells us that this characterised Mark's gospel-writing too ('He paid attention to this one thing, not to omit anything that he had heard, nor to include any false statement among them'). All this gives us good reason to believe that the documents will be generally reliable.

Other types of approach converge on the same conclusion. It was J.S. Mill, no friend of Christianity, who asked the crucial question about the Gospel material: if Jesus was not the source of the teaching attributed to him, who was? The 'community', some critics have answered. But Mill had more sense than that and saw in the Gospel sayings a grandeur that was the mark of a most unusual mind:

Who among his disciples or among their proselytes was capable of inventing the sayings of Jesus or imagining the life and character revealed in the Gospels? Certainly not the fishermen of Galilee; as certainly not St Paul, whose character and idiosyncrasies were of a totally different sort; still less the early Christian writers, in whom nothing is more evident than that the good which was in them was all derived, as they always professed that it was derived, from the higher source.[49]

Which suggests that most of that teaching goes right back to Christ himself.

Modern secular literary criticism provides a further insight: it is incredibly hard to produce a convincing saint-figure in fiction. (Consider Dickens, for instance; his evil characters are full of convincing energy, but the good ones are such pale shadows that it is hard to believe in their triumph.[50] To Dostoevski, there was 'nothing more difficult' than 'to portray a positively good man' in a novel; 'All writers who have tried it have always failed'.[51]) Yet one generation after another has found the Christ of the Gospels an utterly compelling portrayal of goodness in all its robustness and complexity: striking in his teaching, devastating in debate, while at the same time earthy, gentle, totally at ease with the women he knew; and (for example) so sensitive in his meeting with Peter after the betrayal (John 21). Where in the world's fiction do we find anything comparable? But if our best novelists have proved unable to invent such a figure, must we not conclude that the Gospel writers were copying theirs from a real original? To make matters worse, fictional prose marked by such realistic detail and seriousness of purpose simply didn't exist at that time (the novel as we know it is a genre that arose largely in the eighteenth century). So either we must say that the Gospels, with their striking realism of style, are basically factual, depictions copied closely from the real events they describe – or else believe that not one but four great novelists arose, and that these four writers (who were not artists but missionaries) somehow came up with a totally new type of prose writing that would then disappear for centuries; and, bizarrely, each of them also succeeded in constructing a fictional saint-figure no later novelist has been able to match! The thing seems absurd. Clearly, as Lewis concludes, the picture they present of Jesus must have been copied from reality, and be at least 'pretty close up to the facts'.[52]

But there is a final issue, which is often ignored to a quite astounding degree: the early Christians would have wanted as accurate as possible a record of what their Master did and taught.[53] Further, many of them came to very unpleasant ends for their beliefs, and had every reason to want to be certain of their authenticity. The recipients of the early Gospels weren't a flock of spaced-out hippies frolicking on a sunny hillside. One of the early Roman emperors took to using burning Christians as human torches for his garden. If we imagine ourselves in the position of someone who remains a Christian knowing this is how it might end, we can see that those early believers would want to be very sure of the historical basis for their horrendous gamble. People who were dying for the gospel story would want to be certain of its reliability. For all these reasons, then, we may well conclude that these colourful, earthy accounts are at least very close to what Jesus actually said and did.

It is hard to think of Christ as 'a good man', when surely no 'good man' could be so hopelessly lacking in self-knowledge.

But now comes the difficulty. On the one hand, we may be captivated by the shrewdness and sublimity of Christ's words and stories, and the glory of what he does: his identifying with the poor, the broken and marginalized, the untouchables and outcasts; his love for joyous celebrations, matched with his unflinching challenges to entrenched evil; his generosity in healing and forgiveness; the astonishingly moving incident when he washes his disciples' feet on the night of the betrayal. This, we so often feel, is the way to live: if ever life was lived the way it should be, this is that life. But then there is a serious problem. This Jesus who illuminates one moral complexity after another takes an extraordinary line on his own goodness, showing no awareness at all of any wrong in his own heart (in sharp contrast to his followers; cf. Luke 5:8, 1 Timothy 1:15). Indeed he even claims sinlessness. And John the Gospel writer, who knew Christ so well, doesn't flinch (he apparently has no debate to record in which Jesus fends off accusations of sin; indeed, the effect of this claim on many of Christ's hearers is to convince them to follow him – John 8:29-30, 46).

This is disturbing enough. But then come the astonishing claims Christ makes for his true identity, and the massive demands he makes of his disciples (to the point of their self-destruction, if he were not who he claimed to be). No other major religious teacher – Buddha, Muhammad, Lao Tzu, Confucius, Socrates, Paul – ever made such claims. It is hard to think of Christ as 'a good man', when surely no 'good man' could be so hopelessly (arrogantly?) lacking in self-knowledge. The more we grasp the Gospels, the more we find Christ's teaching centring absolutely, over and over again, on his hearers' response to himself. Repeatedly he demands, forces them, to a decision of total discipleship. If he is wrong here, he is a massive egoist and is wrong at the heart of his activity.

There are numerous examples. I must take absolute priority over your parents, your wife and children and everything else in your life, he insists in Luke (14:26); you must renounce everything for me (14:33); you must deny yourself, you must give up your life for me (note, not for the truths in my teaching, but for me; 9:23-24). I am in an utterly different class from all God's preceding messengers (20:9-14); greater than the greatest of Israel's kings (20:41-44); wiser than the wisest of the ancients (11:31); greater than God's own law (6:1-5). Everything has been given to me by God, and only I know what God is like (10:22); your public response to me (again, not to the truths I teach, but to me) will decide your eternal fate (12:8). And there is more; we can try to imagine our reaction to a contemporary making such claims. It is fascinating – considering the uniqueness of these claims among the world religions – that the Gospel writers can cope. Indeed, Luke centres his book's entire structure on Peter's confession of Jesus as the Christ of God (9:20).

John's Gospel takes matters still further. Jesus states that he embodies the life of the resurrection, and anyone who believes in him will never die (11:25-26); he alone gives life to the dead, depending on whether or not they believed on him (5:25-26, 6:40). He, personally, is (not shows) the way, and the truth, and no one comes to God except through him (14:6); he always does what pleases God (8;29,46). Staggeringly, 'Anyone who has seen me has seen the Father' (God) (again, we should try to visualize a contemporary saying that; 14:9); 'I and the Father are one' (for that the Jews tried to stone him, 10:30-31, 38-39). He, not the Father, will judge the world (5:22), 'that all may honour the Son' (himself) 'just as they honour the Father'. He is God's equal (5:18), the eternal 'I AM', the very Creator who hung the stars in space (8:58-59). Perhaps most striking is 5:23: anyone who does not honour Jesus does not honour God; worship of God only has meaning if it is worship of Jesus. More could be cited. For Christ, the whole universe centres on a Person, and he is that Person. We find such claims in every stratum of the Gospel traditions;[54] and in sections too (eg. throughout John 13-17) where the unbiased reader is compelled to sense teaching of a depth and stature that must surely come from Jesus himself. There are so many of these remarkable passages that, even if a couple had been invented by his disciples, the overall shape of Christ's self-image would be unmistakable.

As we have said, the purpose of this chapter is not to state conclusively the basis for Christian hope. We cannot examine the data in isolation from the experience of exposure to the gospels. This section seeks just to set out the question that demands our attention. Which is: How can we deal honestly with the dilemma posed by these passages? Was Christ aware of the falsity of his enormous claims, for which his closest followers would die in agony – that is, he was a conscious deceiver? Or was he unaware – that is, he was a lunatic? Unless – the only other logical option – they were indeed true?

Let's postulate that Jesus was a fraudster, setting up his own bogus personality cult. How can we relate such a notion to our experience of, say, the profundity of the Sermon on the Mount?[55] Can we think of him as a conscious deceiver, recalling how his 'image' had to be maintained through three years of travelling round an often-hostile Palestine with that handful of close disciples that would go on to die for him? If he was a conscious deceiver, how are we to understand the agony that his disciples witnessed in Gethsemane? And why ever did he go to the cross?[56]

'He expressed, as no other could, the spirit and will of God'.

Gandhi on Jesus'I know men; and I tell you that Jesus Christ is not a man… Everything in Christ astonishes me. His spirit overawes me, and his will confounds me. Between him and whoever else in the world, there is no possible term of comparison... The nearer I approach, the more carefully I examine, everything is above me – everything remains grand, of a grandeur which overpowers…'

Napoleon[57]'His penetrating humour, his iconoclastic challenge to the establishment, his devastating calmness in the midst of personal danger, his compassion and respect for prostitutes as sisters, his warm magnetism for children, his redemptive view of crooked politicians, his unorthodox social habits, his deep integrity in the face of full-blown dilemmas – all these characteristics should inspire us to ask, "Who then is this?" The deity of Jesus Christ awes me. So does his humanity'.

Chinese-American writer Ada Lum

It seems impossible. But the alternative of thinking of him as a lunatic is equally difficult, as the shrewdness, simplicity, and sanity of his teaching speak into our lives; or as we watch the calm relational skills he demonstrates in so many varied situations. Claiming to be the very Creator (how could one imagine that?): how could he be so evidently wise, yet so enormously out of touch with his own psyche? And above all in Judaea, a culture shaped through and through by a sense of the utter uniqueness and otherness of God?

In the presence of the Gospels, the choice seems stark. To commit our lives to the stance that Christ was an egoistic trickster, consciously misleading (and so destroying) his closest friends, seems impossible. Therefore we must conceive of ourselves looking him in the face and saying that he was totally lunatic when it came to any perceptions about himself; deliberately or not, Jesus was an utter megalomaniac. The only other option is to commit ourselves to him as the Lord; recognising him as God truly incarnate, prophesied accurately for centuries beforehand,[58] that he claimed to be. For this writer personally, that seems the only reasonable alternative.

These are the basic issues. This book cannot handle all the data, for the reasons indicated earlier. And it cannot replace experience of personal openness to God in the presence of what the historic Christian community has believed to be his 'living word'. If Christian faith is true at all, then we can only find out through placing ourselves in a position of humble (which does not mean believing) openness for encounter with God; by taking our Gospels and saying to God: 'If you are there, if you show me from these pages the truth about my life and about who Christ was, I will follow you wherever you lead'. To Christian belief, each of us stands in the presence of God with the possibility of choice; to take the whole issue off the periphery and expose ourselves to it realistically; to draw, and then live by, our conclusions.

What Jesus Wanted

'Now there was a man of the Pharisees named Nicodemus, a member of the Jewish ruling council. He came to Jesus at night and said, 'Rabbi, we know you are a teacher who has come from God. For no-one could perform the miraculous signs you are doing if God were not with him...'

(Is Nicodemus the prototypical Western intellectual? – passing approving comment but preferring to avoid the necessity of commitment? The liberal, it has been said, always prefers questions to answers...)

Jesus looks him straight in the eye and informs him, 'You must be born again'.[59]

Transformation – as we shall see in a moment, this links in with issues crucial to contexts as diverse as Maoism, the feminist movement, the 'deep-green' movement and the gripings of Britain's own Prince Philip. The problem has been the trivialization of Jesus' phrase 'born again', after two thousand years. How are we to understand it?

'A voice says, "Cry out." And I said, "What shall I cry?" "All men are like grass, and all their glory is like the flowers of the field. The grass withers and the flowers fall, because the breath of the Lord blows on them. Surely the people are grass! The grass withers and the flowers fall, but the word of our God stands for ever...";

'You who bring good tidings to Zion... say to the towns of Judah, "Here is your God!" See, the Sovereign Lord comes with power, and his arm rules for him... Who has measured the waters in the hollow of his hand, or with the breath of his hand marked off the heavens? Who has held the dust of the earth in a basket, or weighed the mountains on the scales and the hills in a balance? Who has understood the mind of the Lord, or instructed him as his counsellor?... Surely the nations are like a drop in a bucket; they are regarded as dust on the scales... Before him all the nations are as nothing; they are regarded by him as worthless, and less than nothing...

'Do you not know? Have you not heard?... He sits enthroned above the circle of the earth, and its people are like grasshoppers. He stretches out the heavens like a canopy, and spreads them out like a tent to dwell in. He brings princes to naught, and reduces the rulers of this world to nothing. No sooner are they planted, no sooner are they sown, no sooner do they take root in the ground, than he blows on them and they wither, and a whirlwind sweeps them away like chaff.

'"To whom then will you compare me? Or who is my equal?" says the Holy One. Lift your eyes and look to the heavens: Who created all these? He brings out the stars one by one, and calls them each by name. Because of his great power and mighty strength, not one of them is missing.''[60]

Throughout the early Christians' proclamation, two basic issues recur, which combined lead to the joyous breakthrough of new birth. Paul summarizes his message in Acts 20:21: 'I have declared to both Jews and Greeks that they must turn to God in repentance and have faith in our Lord Jesus'. Jesus' own proclamation centred on the same two issues: 'The kingdom of God is near. Repent, and believe the good news!'[61]

Repentance is a word we don't much use. Its Greek original, metanoia, means a total turnaround of life. It means recognising a deep-seated wrong direction in our existence, all the wrong thoughts and actions – the arrogance, anger, vindictiveness, greed, petulance, dishonesty we each sense within ourselves from time to time (eg. as I relate to my children, parents, partner) – and determining to do very differently. But there is a deeper level. As we saw in Genesis, the fundamental issue is our attempt to dethrone and exclude God our Maker; our demand for autonomy, our rejection of his Fatherly love. We have chosen, generation on generation and year after year in our own lives, to live without him. It is this, above all, that metanoia confronts. The recognition of the One who sits on the circle of the earth; the acceptance of his claims on us; the realization that, hitherto, we have run our lives our own way, ignored him and often revolted against his purposes. Metanoia means bringing our lives back – to be his, for his glorious, loving, creative purposes, now and forever.

(This is hard for a culture that wants God to be, at most, a guide, not a judge – ironically, the same generation that, like none before it, is using up its planet's resources and bequeathing a poisoned world to its successors. A friend told me recently: You've really understood Christianity when you've understood you need to be forgiven. Liberation is being able to admit that I am not OK, and that that problem has to be dealt with...)

But to recognize the colossal glory of the living God is to realize the dangers in our own position. Once we begin to grasp the idea of a God of infinite majesty and joy, and of devastating purity, we may feel less surprised that we do not experience his presence the way we are! We may even feel relief; we know we aren't exactly 'pure in heart', and therefore (if Jesus is right) we cannot see God.[62] We know our nature is not his; we begin to grasp that to encounter his glory as we are – 'the King who alone is immortal and who lives in unapproachable light, whom no one has seen or can see'[63] – could be a disaster. (To walk into the blinding heat and light of a blast-furnace is to meet with instant destruction. It's significant that the Old Testament's term for something 'devoted' to God sometimes carries with it connotations of destruction; to encounter God's presence, as things stand, outside Christ, might mean just that.[64]) The question Isaiah raises hangs over our situation too: 'Which of us can dwell with everlasting burning?'[65] We know there is the other, indeed more central side of God's nature, that he shows to us in metaphors of 'Father' and 'Lover' and 'Bridegroom'. But that is the God who came looking for Adam and Eve in Old Testament Eden, before everything had finally gone wrong. We are outside now, trapped in our abnormality on a dying globe, wandering as Cain wandered, shut out a long way from home.

(But to be shut out from the light would ultimately be to drift out into the darkness. We would be like an electric fire disconnected from the power of the mains; for now there is some warmth, some love, some joy, but it's cooling down, running out, dying. If indeed God is the true source of all these things, then to keep him on our lives' periphery, to choose to remain a long way outside Eden, would be to stay on course for a condition where finally (outside this life) there will be no love or joy or peace or hope at all: 'shut out from the presence of the Lord'[66] forever, with all the consequences that must logically follow. It certainly isn't what the Father-heart of God would want for us: we think of Jesus weeping broken-heartedly over Jerusalem: 'How often I have longed to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings; but you were not willing!'[67] Logically, though, that is what the exercise of our freedom to stay alienated from God must ultimately involve.)

Nothing can survive in the white heat of a blast-furnace that is not itself transformed into flame. (But what might it mean to be 'transformed into flame'?) So it's not surprising that such a transformation is precisely what God offers us; being filled with his glory, so that we can joyfully live in his presence.... First, however, there is a barrier to be overcome. For we are the generation that had it all and wanted still more; that used up the oceans, the ozone layer and the rainforests and wouldn't stop for our grandchildren's sake; that decimated species after species, watched poverty and genocide multiply, and nonetheless demanded our debts and our profits and grew rich from the arms trade. Racially and individually, we have broken his laws in the everyday issues of how we treat each other and our environment,[68] in our failure even remotely to 'love our neighbours as ourselves'; and most fundamentally in the Eden issue (repeated at different levels in the western cultural process since the Enlightenment) – denying God's reign and centrality, insisting on running our own universe. We can see how we have each followed in Adam's steps, day after day; thanklessly denying that God be God,[69] claiming that position in apartness for ourselves. The consequence of such alienation, says Paul, is death;[70] which is inevitable, if the Father is truly the source and heart of life. We know the physical laws don't change around from day to day; God is a God 'who does not change like shifting shadows'.[71] He is reliable, a God of colossal justice – but that means he cannot deny his own law, cannot just change it for convenience. There is death in the system, and that penalty of death must be paid.

It is for this reason, says the Bible, that the cross happened, that God-in-Christ died; that God himself took our human place, to carry our penalty. When, therefore, we see the Man hanging on a cross and screaming 'My God, my God, why... why have you forsaken me?', we know he has been to the uttermost, darkest limits of alienation – and paid our penalty, and opened the gates back (or onward) to Eden.[72] Here is the centre of history. It is because of the cross, the paying of the penalty and the shattering of the barriers, that the resurrection could occur, that the Father and we can be brought back together. Christ's resurrection was the proof of life's triumph over death, of God's passionate love available now to flood out and remake a lost world. It is after the cross that we can hear the Father challenging us to 'be reconciled to God' – just as he walked in Eden long ago, calling out to the frightened rebels: 'Where are you?'[73]

'You who bring good tidings to Jerusalem, lift up your voice with a shout; lift it up, do not be afraid! See, the Sovereign Lord comes with power... He tends his flock like a Shepherd; he gathers the lambs in his arms, and carries them close to his heart; he gently leads those that have young...

'Why do you say, oh Jacob, and complain, oh Israel, "My way is hidden from the Lord; my cause is disregarded by my God"? Do you not know? Have you not heard? The Lord is the everlasting God, the Creator of the ends of the earth. He will not grow tired or weary, and his understanding no one can fathom. He gives strength to the weary, and increases the power of the weak. Even youths grow tired and weary, and young men stumble and fall; but those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles; they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint.'

Isaiah 40:9‑11, 27‑31

And explosively, it is after the cross that Pentecost can occur. What is Pentecost?

Pentecost, Acts 2 tells us, was when God the Holy Spirit swept down on God's people and filled them, began living in them. We could only survive in the presence of dazzling glory if we were being transformed into that same substance. So that, says the New Testament, is exactly what God does in us. We aren't invited just to 'get religious', to turn over a new leaf. This is nothing short of 'new birth' – the reintroduction of the presence of God turning us step by step into radically different people. With the barriers gone, God comes to live in us. We share in what was gained when God-in-Christ died – which means we can share in his resurrection, 'in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too may live a new life'.[74] There is something deeply corrupt at the roots of our personality, and it cannot be reformed (hence the powerlessness of human religiosity); it simply has to be amputated. At that moment when we are 'born of the Spirit', our 'old self' actually dies, insists Paul, and its place is taken by a new identity shaped by the Spirit.[75] It will take many years of remoulding, reshaping and healing for that new identity to penetrate every area of our values and attitudes and emotions; indeed, the full process won't be completed this side of death. But at least now it can start; and only that in us which is transformed into the radical new nature from the Spirit will survive into God's eternal universe.

This is radical, original Christian faith. 'Repent and believe the good news', declared Jesus. On the day of Pentecost, fifty days after his resurrection, his followers preached the same basis for hope: 'Repent, and be baptized, every one of you, in the name of Jesus Christ' – the submergence of baptism[76] being the cathartic expression Christ had established of the absolute commitment of faith – 'for the forgiveness of your sins. And you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit'. Paul's message was the same, as we have seen – 'I have declared to both Jews and Greeks that they must turn to God in repentance and have faith in our Lord Jesus'.[77]

Turning to God in metanoia, 'repentance': recognizing before him all I have done wrong, and above all my attempts at autonomy from God; turning to him, determined to abandon all wrongdoing, and make him central again, in a confession of Christ as absolute Lord of my whole being.[78] Believing the good news: that God has stepped in, that there is forgiveness and a new order through Christ's death, that the barrier is swept away; 'faith in our Lord Jesus' – staking every aspect of my existence on my conviction that he will keep his promise to forgive, that he will indeed enter, forever, into my life by his transforming Spirit. Consciously inviting his genuine presence: 'If anyone hears my voice and opens the door', promises Christ, 'I will go in and eat with him, and he with me... I am come that they may have life, and have it to the full'.[79] So, faith that Christ will henceforth be there forever, as father, brother, lover, king: identity, direction, relationship, truth, hope.

Real faith is relational, outward-directed. It is not mere 'self-realization', or finding some abstract 'integration point' for its own sake. Jesus actually said that 'Whoever finds his life will lose it'. The quest to 'find myself' and for abstract 'meaning in life' can be self-centred, inward-bound, a decoy away from relationship and transformation. It is, instead, the person who 'loses their life for my sake' that will 'find it', Jesus continued.[80] We live for God's glory, not he for our fulfilment – but that way lies joy. The Father ('undoubtedly the most joyous being in the universe'[81]) is real, and is the Lord at the heart of the cosmos; we are built for his presence, and any apparent substitute is, ultimately, a fatal narcotic rather than food. In the end, nothing else will be enough for us, and what we try to deify – to put in God's place – we merely destroy, as we have seen. Augustine had it right fifteen hundred years ago: 'Thou hast made us for thyself, and never will our hearts find rest until they find their rest in thee'.

The end of emptiness; this is what being 'born again of the Spirit' first meant, and it's vital to understand that if we're to grasp the Christian stance in the contemporary crisis. If radical Christianity has anything to offer, then Christ's challenge to Nicodemus is central to it. The intellectual pose that deigns merely to approve of Christ, and incorporate that approval into an analysis, will get us nowhere. What our century demands is power that can offer some genuine transformation. The Christian asserts, with the French philosopher Pascal, that there is indeed a space in human beings in the shape of God, and that that space must be filled in very actuality if things are to begin to be put right. Jesus' challenge has to be taken seriously. It is only 'new birth', with the reintroduction of the presence of God, that can begin to produce radically 'new humanity'.

Which brings us, somewhat circuitously, to Prince Philip and Che Guevara.

The Renewal Deficit

The issue of power for transformation is a major one as the new millennium gets underway.

'It's inevitable that very grave damage is going to be done to this world in the next hundred years', Britain's Prince Philip told Women’s Own a while ago. What could be done? 'Search me. I don't know. The older I get, the more cynical I get, in the sense that I just think things are going to get worse. I mean, there was a period in this country when you could leave your car unlocked, your front door open, when you could trust anybody across the social scale. Now you can't even trust your neighbour'. Or, as someone else has said: we've made it possible for a man to walk safely across the moon; we can't make it possible for a woman to walk safely across London. (Or Marseilles, or New York, or Berlin.)

It's hopeless. That's my view. I believe there's no chance of the world coming to other than a very grisly end in twenty-five years at the outside. Unless God, as it were, finally speaks. Because reason is not going to do anything… Finally it's hopeless. There's nothing one can achieve.

Harold Pinter.

Crisis faces us on so many fronts. 'Green' issues have grown in importance in the last few years as we've realised what the greenhouse effect, the hole in the ozone layer, and the death of the oceans will mean. With that awareness come fear and a deep sense of powerlessness: the sense that 'very grave damage' is indeed being done by structures far beyond our influence or control. Yet even the new environmental awareness might seem essentially self-centred; it seems we have reacted far more strongly to these issues than to the appalling realities we have known for years to be crippling the vast majority of the world. For example: 250,000 children will go permanently blind this year for lack of a daily vitamin A capsule worth a few pence, or a daily handful of green vegetables. Twelve million children die each year – over a thousand each hour – from common diseases or malnutrition, most of whom could be saved at very little cost; two million die from diarrhoea, for example, for whom a solution of eight parts sugar to one part salt in clean water is all that is needed. Over a thousand women a day die in childbirth (a process 150 times more dangerous in the two-thirds-world than in the West) for lack of nutrition or trained medical personnel.[82] (Meanwhile, a good proportion of our own scientists and engineers expend their talents on the creation of ever more destructive weapons; and that's also how we spend taxes that could genuinely transform African health systems.[83]) We might wonder how many women, widows especially, will take the step into prostitution this year because it is that or starvation for their families; or how many desperate parents will sell their children into slave labour or sexual exploitation in the brothels of cities like Bangkok for the same reason.[84]

It cries out for change. It cries out for something that can actually take the people with the money and power and turn them into people who care for the poor (and the planet); equally, that will take the people with the skills and resources and send them to pour out what they have where the needs are greatest – both in the emergency zones and inside the crucial decision-making structures. But what power could do that in people's hearts today? How to turn me-generation yuppies inside out, into 'new people' who are genuinely serious about real self-giving, and will take at least the first steps towards some real transformation?

The question has been on the agenda in the best parts of the 'New Age', 'deep green', and feminist movements. And also on the left, though with a tragic record of failure;[85] 'If our revolution does not have the goal of changing men it doesn't interest me', Che Guevara remarked. But if (as the majority of the human race has always affirmed) there is a God, then logically it would be in that direction that we should look first for power for such fundamental 'surgery' and re-creation. If (as we can consider for ourselves) there is solid, factual reason to believe that in Christ God actually broke the old order of defeat and entropy, and proved it by the tangible reality of the resurrection; then this is the kind of 'new birth' that must be available.

What kind of 'new life', based on the rediscovery of God's genuine presence, might we expect to follow?

Paths of Transformation

One of the key issues dividing radically biblical Christians from nominal European religion has long been the radicals' insistence that faith's goal isn't merely to produce nicer people (nor, certainly, to 'give comfort in troubled times'). Rather, it is to bring to birth dramatically new people, whose life centres on the presence of God, and invest effort in an entirely 'new kingdom'.

Precisely this was the vision of Jesus' immediate followers. Paul defines the point of it all in a thought-provoking section of his most 'central' letter, Romans: 'Those God foreknew, he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son'.[86] Life isn't meaningless, he's saying; rather, God has lovingly 'foreknown' and orchestrated ('predestined') all the life-circumstances of each person who responds to the 'new birth', like a brilliant symphonist or dramatist. If we've given ourselves to his purposes, then the meaninglessness stops; every friendship, every anguish, every book or encounter or learning experience, is now growing together into a design of unimaginable, long-term transformation. (That doesn't mean believers are now 'better people' than not-yet-believers; but it does mean God is at work restoring broken people, and believers have stepped out into the restoration process.) And the Father's aim in this is to sculpture, in each of us, something unimaginably glorious: an identity so 'transformed into Christ' that eventually all the love, peace, joy, and power for goodness of Jesus start flowing out through us. (The apostle Peter talks about our 'participating in the divine nature'; John's vision is that 'when he appears, we shall be like him'.[87]) It's a tough thought for our intellects to seize; for most of us it will take an enormous amount of doing…. yet the power guaranteeing it is that which formed the universe out of nothing. Paul tells the Galatians he is 'in the pains of childbirth until Christ is formed in you'.[88] His goal echoes the vision we saw in Genesis, man and woman created as a visible expression of God's nature – and now that begins to be consummated at last. Indeed, Paul goes further: the aim isn't just to make us 'like' Christ (until we've grasped what Jesus is like, that might sound a trifle dull), but actually to see 'Christ formed in you', to make us 'in' Christ, to unite us with the eternal glory, living in him and he living in us; what Paul gets really enthusiastic about is the 'glory that will be revealed in us'.[89]

Really knowing God, really being changed, really being unified with his glory. Following Jesus isn't just about being nicer, or having a series of 'moral values'; rather, it’s about passion and worship, about reuniting with the purpose we were made for, a purpose extending far beyond our planet and its transient history. Nor is Paul inviting us merely to some private mystical ecstasy. In the same passage (Romans 8) he looks out across a whole cosmos groaning in futility, enslaved to laws of decay. And he knows, both from his own unique experiences[90] and from the proven fact of the resurrection, of the intrusion into this world's tragedy by an alternative order;[91] knows there is a different reality available. It is a new heaven and new earth, characterized not by the sad, deterministic cycles of entropy where everything winds down and falls apart, but by that alternative principle which Paul had spelled out three pages earlier: 'Grace reigns!' Grace – God's passionate love bringing something out of nothing; the God who once spoke creatively to bring light out of darkness, working actively, lovingly and creatively still.

Precisely this is what we see Jesus announcing and demonstrating, very practically, in one of the most famous and radical parts of the new testament. He began his public activity by declaring that a whole new order, the 'kingdom of heaven', was now within reach (Matthew 4:17). And he embodied it: 'Jesus went throughout Galilee teaching… preaching the good news of the kingdom, and healing every disease and sickness among the people. News about him spread all over Syria, and people brought to him all who were ill with various diseases, those suffering severe pain, the demon-possessed, those having seizures, and the paralysed, and he healed them' (4:23-24). And then, just as 'large crowds' were turning out, thinking that God's reign 'on earth as it is in heaven' (6:10) might be quite a pleasant diversion, Jesus sat them down (5:1-2) and began to explain that joining that 'kingdom' involves following him (4:19-22) into deep transformation far beyond their own ability to achieve, a lifestyle based on radical overturning of all the old system's values.

Speed-reading the first five chapters of Mark's Gospel is a good way to grasp the nature of the 'kingdom' Jesus announces. Chapter 1 chronicles his first astonishing advance, where Jesus reveals his power to put things right in the face of ignorance, sickness, and demons. Chapter 2 expresses the kingdom's joyous positiveness (2:19, 22, 23-28, 3:4-6), the way its love has strength to draw in the excluded (2:16-17). Then, after the kingdom's initial rejection in chapter 3 and its explanation in chapter 4, comes a further section revealing its power in action, triumphant over destructive nature, demonic evil, even death itself (4:35-5:43). We also watch Christ bringing purpose to individuals (1:16-20, 2:13-17), astonishing the villagers with huge new vistas of truth (1:27,38), and bringing joyous liberation ('new wine') from the constrictions of false religion ('old wineskins', 2:21-28). The 'good news' is firstly about forgiveness of sins (2:5), because dealing with that blockage is the gateway to everything else; but through this gateway a whole glorious new order floods in. Where Christ comes, the kingdom comes, and the kingdom reveals the heart of God: bringing truth where there was falsehood, love where there was hate, healing where there was pain, wholeness where there was brokenness.

Above all what Jesus brings is goodness. Reading how the new creation bursts into our world in these chapters, aren't we reminded of the repeated refrain describing God's handiwork in Genesis 1: 'And God saw that it was good'?

'Blessed are the poor in spirit', he said, those who realize they haven't 'got it sorted'. 'Blessed are those who mourn', who are deeply frustrated with the evil in themselves and in the world; 'Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness', because they will see the new kingdom, they 'will be filled' (Matthew 5:3-6). Jesus' alternative order centres on values about which the crumbling old system is utterly sceptical. He spells them out uncompromisingly: radical commitment to reconciliation, purity, total marital faithfulness, trustworthiness, generosity, refusal of revenge ('Love your enemies') (5:21-48). First, though, he simply declares, 'Blessed are the merciful… blessed are the pure… blessed are the peacemakers'. The 'pure' (the 'naïve')? – those who miss out on all the fun? The 'peacemakers' (ditto the 'naïve')? – who end up getting hated by both sides? Yes, said Jesus (who himself would end up crucified) – blessed, even, are those who get persecuted for the new order, 'for theirs is the kingdom of heaven'. Heaven's order is already here, embodied within all who commit themselves to its Lord; like grains of salt (5:13), tiny, yet flavouring, even preserving, what's around them; facing ridicule, opposition, even outright hatred, but nonetheless pursuing what is the only way to live, because it reflects the dynamic of the 'real', eternal world.

So the new universe of heaven doesn't stay (as Graham Greene once wrote) 'rigidly on the other side of death';[92] rather it begins to erupt into our world. To return to Paul in Romans 8: 'I consider that our present sufferings are not worth comparing with the glory that will be revealed in us. The creation waits in eager expectation for the sons of God to be revealed. For the creation was subject to frustration... in hope that the creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the glorious freedom of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time. Not only so, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait...'[93] So from its human bridgehead ('firstfruits'), the freedom of the new resurrection order must flood out across a dying creation. As Jesus promised: 'Whoever believes in me... streams of living water will flow from within him' – that life-giving water being, as John immediately explains, the supernatural energy of the Holy Spirit.[94] If it isn't so, our faith isn't real.[95] True, our world's transformation will not even approach completion without the direct intervention of God himself (indeed the biblical material speaks of history closing in a final, nightmarish crisis, where the logic of our alienation from God culminates in domination by a dictator entirely given to evil[96]). But Christ's followers are called to be agents and footholds of the future transformation. The Spirit's energy that starts to flow within us, Paul affirms repeatedly, is a 'deposit, guaranteeing what is to come'[97]; living, life-giving water flowing – trickling or gushing – out into a desert world; the point where God's new order breaks in right now.

Visionary stuff. But what does it all actually mean?

It means, first of all, that 'new birth' is not just a mental adjustment, to be reflected in a more accurate tax return, a tendency not to kick the dog and a new found interest in attending church services. It means an absolute reversal of the loss of the presence of God that we have considered throughout this book. It means new identity as a 'child of God', and a passionate commitment to express in practical action the love and truth of Christ. It means an all-consuming purpose, summed up in Paul's paean of longing: 'Whatever was to my profit I now consider loss for the sake of Christ. What is more, I consider everything as loss compared to the surpassing greatness of knowing Christ.... I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the fellowship of his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, and so, somehow, to attain to the resurrection of the dead'.[98]

Indeed, the Way of the crucified Christ in the west's disintegration may easily involve that 'fellowship of his suffering'; in apparent abnormality or real 'loss' (promotion, sexual fulfilment, status), in association with unpopular causes or minorities, we may be called to 'know' more deeply the Christ nailed up between heaven and earth. The cross was where Christ absorbed the evil from the world, as with a sponge; his people are called likewise to break the patterns of self-perpetuating evil by going the way he so radically taught – forgiving, refusing to retaliate, being truthful, outdoing evil with generosity.[99] (Hence the centrality of the celebratory meal of communion that refocuses us on the cross; bread symbolizing Christ's broken body, wine his blood poured out.) And, as they set out to do so, to experience more of his resurrection strength: 'Whoever loses his life for my sake will find it', promised Jesus uncompromisingly.[100] Transformation is grounded in the cross: 'We... are always being given over to death for Jesus' sake', says Paul, 'so that his life' – Jesus' presence and reality – 'may be revealed in our mortal body'.[101] Heaven starts to break in – or break loose – now.

What is 'knowing Christ'? The New Testament points us to at least seven key aspects, involving thoroughly un-mystical, down-to-earth activity.[102] The first challenge is to learn a genuine, ever-deepening relationship with Christ: day by day to 'know' – absorb – more of his supernatural love for others, more of his energy and presence. It’s not just about a sterner moral muscle or better attempts to be nice, but a directly personal power in place within us that enables us, choice by choice, to forgive and apologize and mend relationships, to care and to communicate, to work for radical change, to discipline our own egos. 'You will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you', said Jesus, because being 'born again ... of the Spirit' is the way we enter his family.[103] Obviously our availability to someone who can be called the 'Holy Spirit' implies a life continually grounded on a hunger for holiness. But on that basis, we are told we can ask with assurance for more and more of his presence. 'Which of you fathers, if your son ask for a fish, will give him a snake instead?' asked Jesus. 'If you then, though you are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him!'[104]

There is a vital link between this and our immersion in the Bible. Paul describes exactly the same things as marks of someone 'filled with the Spirit' and of someone who has 'let the word of Christ dwell in you richly'.[105] Jesus taught that the Scriptures had a unique status, unlike any other words: 'The words I have spoken to you are Spirit and they are life' – not just symbolic expressions for the presence of God, but that presence itself.[106] To read them in the presence of God is to meet God; as Chesterton said, a Jesus-follower is like someone who is 'always expecting to meet Plato or Shakespeare tomorrow at breakfast'.[107] What we read embodies the 'living and enduring' Word of God that is (as the apostle Peter puts it) God's 'imperishable' seed within us – the point where his new, undecaying order breaks through.[108] Paul makes clear that it is in the practical experience of in-depth Bible reading that we grow renewed, 'transformed into his likeness with ever-increasing glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit'.[109] Time in God's presence is, to borrow a phrase of Eliot's, the 'still point of the turning world': the gateway for the grace and the strength of God.

Such transformation takes place within relationship. So, as God speaks to us through his Word, we respond directly in prayer and in worship. A deepening vision of what God is like draws out a response in love and thanksgiving; a deepening perspective on the situations around us draws out a response in prayer, God's primary means whereby the transforming powers of heaven are released into this world.[110] And, unless we are just trying to play games with our faith, there will be many other results from this encounter, in terms of gradual but genuine changes in our own thought‑patterns and lifestyle. Prayer involves learning to perceive situations as God does, and receiving the strength to respond as he would. 'Be transformed', says Paul, 'by the renewing of your mind'.[111]