Deconstructing a Worldview

How do we start thinking through ideas carefully so that we can help people glimpse the truth?

If I am to help people who are not interested in looking at Jesus because they are quite happy with what they believe, I must first set about understanding what it is that they believe. I must do everything I can to understand their worldview. Only then shall I know what kinds of questions to raise with them. In the next two chapters I shall try to show how we can do that. In this chapter I shall look at the principles involved, and in chapter 5 I shall illustrate this with a specific example. It is important to note, however, that these two chapters will tell you nothing about how to use positive deconstruction in a conversation with a non-Christian. I shall do that in chapters 6 and 7. These two chapters (4 and 5) are simply about the preparation process – the study we need to do ourselves, so that we can then help non-Christians to rethink their beliefs.

This preparation is important, as missionaries have known for years. If God called you to be a missionary in another culture, you wouldn’t just hop on a plane and get started. Instead, you would begin by learning about the culture and its worldview – what the people believe, why they believe it, and how you might be able to help them to turn from false beliefs to the truth which is found through Jesus. This would take time and effort on your part. If the place to which you were going contained a mixture of cultures, you would need to get to grips with each of them, and that would take even longer.

It is important to recognize that today’s western world presents the same challenge that many missionaries have faced for years. We are currently living in a situation demanding multi-cross cultural mission.

Now, of course, most of us can’t take time out to learn about all the worldviews that surround us. Many of us must learn as we get on with evangelism day by day. But if we are serious about reaching people with the gospel, we must also be serious about studying the worldviews that have been absorbed by the people we are trying to help. In this chapter I shall offer you an approach which I find helpful as I attempt to do this.

The process of positive deconstruction

The process of positive deconstruction involves four elements: identifying the underlying worldview, analysing it, affirming the elements of truth which it contains, and, finally, discovering its errors.

1. Identifying the worldview

Most people seem unaware of the worldviews they have absorbed, which now underlie their beliefs and values. That is why it is so rare for people to articulate a worldview. Normally they will simply express a belief or live in a certain way, without knowing or even thinking about the worldview from which their belief or behaviourderives.

Many students tell me they are not interested in hearing about Jesus. But few of them say, ‘That’s because I’m an existentialist’, or ‘That’s because I’m a scientific materialist.’ Generally, they are not at all aware of the underlying philosophies they have adopted. They reveal these philosophies by the statements they make, but they seem largely oblivious of them.

For instance, many students say to me, ‘There’s nothing wrong with me having sex with my girlfriend (or boyfriend). There can’t be anything wrong with something that comes naturally.’

When I ask them why they say that, and in particular if they know where this belief comes from, it is only rarely that students know they are expressing a belief which comes from the underlying worldview of naturalism, with all that this entails (as we shall see in chapter 7).

At the same time, most Christians are not normally aware of the worldviews underlying the ideas of people we are trying to reach. All too often we work at a surface level, reacting to individual statements or behaviour instead of endeavouring to respond to an underlying philosophy. Quite often, when I have sought to teach other Christians about a currently influential worldview, some have said, ‘I don’t know anyone who holds that view.’ But when I give them examples of the kinds of beliefs or behaviour that stem from this worldview (that is, the types of things people will say or do if they have absorbed it), their attitude changes.

For instance, I was recently teaching a group of Christians about paganism. One objected that she didn’t have any friends who were pagans, so this wouldn’t help her. I asked her if she knew people who say that they are not Christians but that they do believe in spirituality.

Yes, she knew plenty of people like that.

And did she know any who would say that organized religion has mucked up our true original spirituality, so we need to rediscover an earlier spirituality?

Yes, some of them said that.

And did any of them believe that, as we develop our spirituality, we must do whatever comes naturally, as long as we don’t hurt anyone?

Yes, again, some of them live that way.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘these people have absorbed elements of a pagan worldview.’

She didn’t realize that, and no doubt most of the others in the group didn’t either, but this underlying worldview is where these ideas came from. The penny dropped for her that night as she saw how important it is to understand the underlying worldview. She had been responding to the surface and not the foundation, the effect and not the cause.

The first task of the process of positive deconstruction, then, is to identify the underlying worldview. This requires us to have a grasp of a wide range of worldviews. We cannot find something if we don't know what we are looking for. Essentially this is a ‘pattern-matching’ process. I have in my mind a large number of contemporary worldviews and know the kinds of beliefs and values to which they lead. Then I consider the beliefs and values being expressed by a person (or in a book or a film) and I look for the best match (or selection of matches) to identify the underlying worldview or worldviews.

Of course, this isn't easy, since it requires us to be familiar with a large number of contemporary worldviews. And most of us aren’t. It may seem strange, but the fact is that, although we are surrounded by many different worldviews, most of us don’t know what they are. A major reason for this stems from the fact that most of us don’t come across them in any pure or easily identifiable form. In chapter 2 we saw that most individuals hold a reduced and combined mixture of worldviews, because of the ways in which they adopt them. Now, we shall see that popular culture itself contains a similar mixture, because of the ways in which they develop, pass into and circulate around the culture.

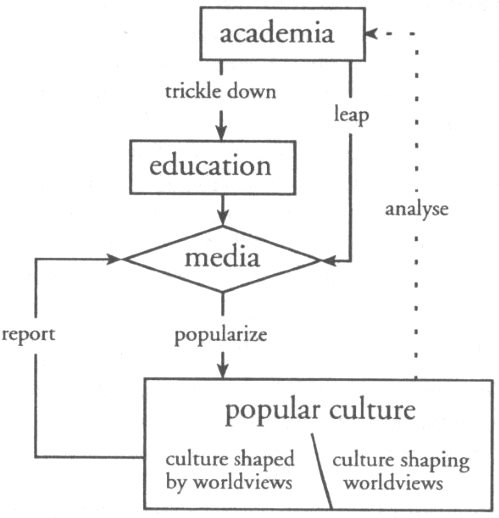

In the past, worldviews have usually stemmed from academic institutions or their equivalent. Here, clear thinkers (from Plato to Marx, from Descartes to Feuerbach) have developed new ideas, or combinations of ideas, in a fairly pure form. From there the worldviews may trickle down slowly into educational establishments, and then into the media, which popularize them into the culture. Or (increasingly) they may simply leap into the culture through the media. Either way, as they are popularized, the pure worldviews tend to become reduced and combined with others.

Assorted bits of worldviews tend to be utilized and combined with bits of others as they are absorbed into popular culture. In turn, this popular culture feeds the media, and a circle develops in which mixed-up, reduced and combined worldviews are reported and recycled, without much re-analysis at the higher level.

I said this happened ‘in the past’, because recently the process of the development and spread of new worldviews has become even more complicated. Some new ideas, or combinations of ideas, still originate in academic institutions or their equivalent. But increasingly, they also originate in television production studios, fashion houses or recording studios, or within club culture or on the street. People living and working at this level thus both shape and are shaped by the culture as they create a fertile ground for the development and spread of new ideas. When this happens, the academics are reduced to observing and analysing new ideas rather than originating them (see Figure 2).

This dual origin and development of worldviews tends to lead to a complexity in contemporary culture, and to some interesting anomalies. For instance, as I write this book, two very different worldviews are being developed and popularized from the two different sources. Academia and ground level seem to be diametrically opposed.

Currently a lot of academic work is being published [see Francis Crick, The Astonishing Hypothesis (Simon and Schuster, 1994); Roger Penrose, The Emperor’s New Mind (Vintage, 1990); and Nicholas Humphrey, Soul Searching (Chatto and Windus, 1995); among others] which seeks to demonstrate a purely physiological explanation for consciousness (or the soul). This seems to develop and justify a materialistic worldview with no recognition of the supernatural, or any spiritual dimension. At the same time, however, a very different worldview is being developed and popularized at ground level. As I write, three of the books in The Times hardback and paperback ‘top ten’ are centred on claims of the paranormal, the television series The X Files is riding high in the ratings, and every Saturday evening Mystic Meg gives her predictions about the National Lottery. As academics are seeking to develop and popularize materialism, others are pulling in the opposite direction. If we are to engage meaningfully with people in contemporary culture, therefore, we must begin by extracting and identifying the underlying worldviews from its multiple complexity.

This isn’t going to be easy. Manifestly, it is not possible for all of us to have a full understanding of all existing worldviews. We can, however, begin to develop an initial understanding of some of the most influential. And resources are being set up to help us all to find this slightly less difficult (see the Appendix).

2. Analysing the worldview

Once we have identified a particular worldview, we can now move on to the next process, which is to analyse it.

Essentially, we have to ask, ‘Is it true?’ To do this I find it best to employ the three standard philosophical tests of truth – the coherence, correspondence and pragmatic tests. This means that basically I ask three questions. Does it cohere? (That is, does it make sense?) Does it correspond with reality? Does it work?

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

First, does it cohere? This question derives from the theory that holds that, if a statement is true, it will cohere. That is, truth will make sense. It will not contain logical inconsistencies or elements that are mutually contradictory. Something which is incoherent cannot be true. It cannot be true if it does not make sense.

Let me give you an example of a statement that will fail this coherence test. Suppose I told you that I don’t believe in astrology, because I was born under the star sign of Aquarius and Aquarians don’t believe in that sort of thing. Do you see how this statement contradicts itself? It is logically inconsistent. As a statement, it doesn’t make sense. So it cannot be true.

Secondly, does it correspond with reality? This question derives from the theory that says that if a statement is true, it will correspond with reality. That is, truth properly describes the real world and does not make claims inconsistent with reality.

Let me give you another example of statements that fail this correspondence test. Mormons believe that Christopher Columbus was not the first person to discover America. They claim that, hundreds of years before Christ, a group of people led by a man named Lehi travelled there from the Middle East and founded a great civilization including such people as the Nephites and Lamanites. This story is coherent on its own terms. It does not, however, seem to describe the real world. I am not aware of any evidence that such a civilization ever existed. It is a great story, but its claims simply do not correspond with reality.

Thirdly, does it work? This statement derives from the theory that says that, if a statement is true, it will work. That is, truth enables us to function, whereas error does not.

The story is told of a politician, a vicar and a Boy Scout who travelled together in a plane. Suddenly, the engines failed. The pilot bailed out, leaving only two parachutes between the three of them. Immediately, the politician said, ‘I’m the most important, intelligent person here, so I’m taking one of the parachutes.’ And he jumped out. The vicar turned to the Boy Scout and said, ‘You take the other parachute and save yourself. I am not afraid to die.’

‘But you don’t need to,’ replied the Boy Scout, ‘because the most important, intelligent person in this plane has just jumped out with my haversack on his back.’

No matter how much the politician believed that the haversack was a parachute, he would soon find out that it wouldn’t work. So his belief wasn’t true. If it doesn’t work, it can’t be true. These three theories of truth and the questions which derive from them provide us with a structured means of analysinga worldview. They give us a framework of three crucial questions we can ask.

It is important that we use all three of them, because each one on its own is not sufficient. If a statement fails one of these tests, we know that it cannot be true. If it passes just one or two, it is not true. It needs to pass all three.

Not everything that coheres is true. My daughter tells some wonderfully coherent stories about how somebody else must have come and put the dirty marks on the wallpaper or broken that vase. The tales make sense, but they aren’t true.

Not everything that corresponds with the reality that we see is necessarily true. For thousands of years people believed that the Sun orbits the Earth. That is what they saw. It corresponded with their perception of reality. But it was not true.

Not everything that works is true. I knew a doctor who gave bright-red vitamin tablets to a patient with a recurrent complaint and told her that they were a new, expensive treatment that was bound to solve her problem. She got completely better. The ‘medicine’ had worked, but it was not true that it was a medicine. Scientists would have called it a placebo.

When we look at any worldview, then, we need to ask all three questions about it. Does it make sense? Does it correspond with reality? Does it work? As we do so, we can look for elements of truth that we may affirm as well as errors that we can discover.

Let me explain what this means.

3. Affirming the truth

Many of us are uncomfortable with the idea that any non-Christian worldview might contain truth. Somehow the notion that we don’t have a monopoly on truth seems to threaten us. It is much easier for us to believe that others are totally wrong and that we are totally right. But this is simply not the case. Non-Christian worldviews are not totally wrong. They do contain elements of truth (sometimes very large), and we must affirm them. If we fail to do so, people will not listen to us, and why should they? No-one wants to be worked over by an arrogant bigot. On the other hand, as we shall see later, they will engage in discussion with someone who is on their side, also seeking after truth.

But there is another reason it is vitally important that we affirm the truth in other worldviews. And this has nothing to do with reaching others; it is to stop us from backing off into error ourselves. Whether we like it or not, other worldviews contain truth. If we reject them totally, we shall find that, as well as rejecting error, we are also rejecting truth. And if we reject truth, we push ourselves into error. Let me give you an example.

Historically, Christians have followed the way of Jesus and have been intimately involved not just in proclaiming the message of love, but also in demonstrating it by social action. Around the beginning of the twentieth century, however, this changed, and the church temporarily lost its social conscience. Why was that? It was partly due to a reaction against theological liberalism, which reduced the value of the Bible and increased the importance of social action. Instead of just rejecting part of theological liberalism (the devaluation of the Bible), many Christians rejected all its insights and consequently rejected social action. If only we had affirmed the elements of truth that liberalism maintained, we should not have thrown out the social action baby with the biblical-criticism bathwater. If we are not going to push ourselves into error, we must affirm truth wherever it is, knowing that ultimately all truth is God’s truth and all worldviews contain elements of this truth.

4. Discovering the error

As well as containing truth, however, non-Christian worldviews also contain error. Jesus makes exclusive claims. If they are true, alternative worldviews cannot be totally true.

When we analyse a worldview using the three criteria of truth, we are attempting not only to affirm truth but also to discover those errors. We may find that a particular worldview is not coherent, or that it doesn’t correspond with reality, or that it will not work, or indeed any combination of these. This, of course, is where we are aiming. It is a prerequisite that we identify the worldview; it is necessary for us to analyse it; it is valuable for us to affirm the truth that it contains; but it is vital that we discover its error. Only then shall we be able to help people see this error for themselves so that they become uncomfortable with their current view and begin looking at Jesus.

This can be uncomfortable for us too

Sometimes, thinking through a non-Christian worldview can take a long time and can be quite a disturbing process. I often find that I go through three phases as I subject a new worldview to positive deconstruction.

Initially, I may have an emotional reaction born of ignorance. Sometimes I catch myself thinking, ‘What a load of rubbish! How can anyone believe this?’ I am not alone in this. It is a common reaction among Christians, and unfortunately it is often due to the fact that we have read not the source material but someone else’s biased summary of it. Thus we are actually reacting not to the worldview itself, but rather to a caricature of it. Sadly, some do not get beyond this stage, and seem only to ridicule other people’s genuine and sincerely held beliefs.

I can move out of this phase only by finding out about the belief. So I set about reading the source documents and talking to people who hold this worldview, or elements of it. When I do this, I begin to find that it is not such a load of rubbish after all. I begin to understand their arguments. It starts to make sense. It may even begin to sound convincing. Sometimes I get a sinking feeling as I wonder whether they might actually be right after all – perhaps I should give up my faith. Again, unfortunately, some Christians reach this stage and do not move through it. They either give up being Christians or put on Christian blinkers, refusing to think about anyone else’s beliefs again, and certainly deciding never to engage in personal evangelism any more. ‘It disturbs my own faith too much,’ they say.

Identify

| Affirm Truth | Discover Error | |

| 1. Cohere? | ||

| 2. Correspond? | ||

| 3. Work? |

Figure 3: Positive deconstruction worksheet

Finally, I step back and, having understood the worldview, I set about subjecting it to positive deconstruction. I usually sit down with a work sheet (as shown in Figure 3) and work carefully through the worldview. I ask the three questions, and for each one I write down what truth I can affirm and what error I can discover. (In the next chapter I shall give an example of this as I use the worksheet as a framework for subjecting relativism to positive deconstruction.) As I do this, I usually have a series of what psychologists call ‘Aha!’ experiences. Light dawns on particular aspects of the worldview and, while I find truths to affirm, I also discover errors. At last I move into the final phase, where I am able to respond to the worldview intelligently and fairly.

I know it isn’t easy

When I have spoken about this process at conferences or training courses, occasionally some have said, ‘I'm not sure I could ever understand this, let alone do it. Does that mean I can’t be effective in evangelism?’

The answer is ‘No’.

The fact is that if we genuinely want to be available for God to use in reaching others, he will use us – whatever knowledge we have. If you were to hop on a plane right now, to a culture you don’t understand, God could use you in that situation. But you would be of much more use if you first set about understanding the culture and the worldviews that underlie it. Of course, that isn’t easy. Preparing missionaries to go overseas never has been easy. Nowadays, those of us who stay at home and want to reach people here are facing the same difficult task.

Understanding the many and varied complex ideas and philosophies in today’s world is going to be difficult. It is far simpler to learn how to sing a song, or act a sketch. But it must be done. This is especially true for those of us who want to reach today’s young people. Gone are the days (if they ever were) when to be effective in youth ministry all you needed to know was how to give your testimony and how to play table-tennis. Today, among many other things, we need to be able to understand and respond to a wide range of worldviews. This is difficult, but if we won’t do it I fear we shall fail a whole generation.