Assessing Aquinas

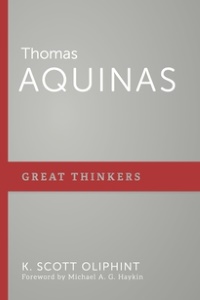

Thomas Aquinas’ influence on Christian thought cannot be overstated. Whether within systematic theology, philosophical theology or Christian apologetics, his influence has been considerable. So it is not surprising to see Thomas selected as one of the studies for the P&R 'Great Thinkers' series.

K. Scott Oliphint wisely restricts his analysis of Thomas’ thought to his epistemology and his doctrine of God’s existence (both his Five Ways and his arguments for the simplicity of God).

A ruthless critique

Oliphint’s critique of Thomas’ epistemology is ruthless, but rightly so, if his representation of Thomas is accurate, a point to which we will return. He argues, for example, that, ‘There are a number of significant and serious issues at stake for anyone who is concerned to affirm a biblical, Reformed epistemology’ (31). What leads him to this conclusion? Oliphint argues that Thomas’ faulty exegesis of Romans 1:19–20 and John 1:9 results in natural reason receiving a heightened position above even divine revelation: ‘The question is whether Thomas sees his philosophy as grounding theology, or theology as grounding his philosophy’ (25). Oliphint’s ultimate charge is that Thomas has not acknowledged the noetic effect of the fall: ‘What the medieval, including Thomas, neglected to incorporate in their theological system was the radical effect that sin has on the mind of fallen man’ (33).

In the second part of the book Oliphint addresses Thomas’ ontology, both with regard to his five proofs for God’s existence and his doctrine of divine simplicity. In this section he argues that the epistemological ground Thomas has laid leads almost inevitably to further problems. For example, Oliphint demonstrates how the apologist who accepts Thomas’ epistemology inevitably concedes ground to the atheist in any debate because he already accepts the pre-eminence of natural reason:

The humanist sets the stage by affirming his allegiance to ‘scientific inquiry,’ by which he means, in part, empirical investigation by way of the natural reason of both interlocutors. The Christian then attempts to stand on the humanist’s ground. He sets his own argument within the context of a supposedly neutral rationality – natural reason. (85)

Oliphint is right to be concerned about establishing a conviction over the noetic effect of the fall. Though this doctrine is affirmed within Reformed theology, it is often overlooked, in practice at least, by many evangelicals. And yet the theological, pastoral and apologetic implications of the doctrine are vast. Oliphint focuses mostly on the apologetic implications, but the theological and pastoral should also not be overlooked. Pastorally this doctrine humbles us before God, and casts us upon Scripture as God’s precious revelation to us. In this, Oliphint is right to highlight the pitfalls of a more evidentialist apologetic method as opposed to a presuppositional approach.[1]

A fair representation?

And yet there is the lingering question: is Oliphint fair in his assessment of Aquinas? Consider, for example, one of the more bemusing statements that Oliphint makes is: ‘Natural reason, in the way Thomas uses it, does not allow for one who is truly infinite, eternal, and immutable; it certainly does not allow for one who is triune’ (88). For those familiar with Aquinas doctrine of God it’s difficult to see this as a fair representation.[2]

While Oliphint certainly provides a helpful and much needed corrective to theologies that neglect the noetic effect of sin, his critique of Aquinas fails to incorporate the idea of common grace – the non-saving grace that God shows to all. Common grace is seen, for example, in the fact that God ‘sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous’ (Matthew 5:45). Similarly, God gifts non-believers as well as believers with imagination and reason. The noetic effects of the fall are real, but we must balance this understanding with God’s gracious limitation of sin’s effects. So this doctrine has clear implications for how we engage with non-believers' cultural and intellectual works, and must also inform our assessment of Christian thinkers like Aquinas. Without an understanding of this key doctrine we might end up believing our apologetic and evangelistic endeavours to be utterly fruitless, and thus give up the whole endeavour of persuasion. And yet the Bible consistently teaches that God, in his mercy and grace, does enable points of contact and connection with those we seek to reach with the saving gospel of grace. For an effective and fully biblical apologetic we need to acknowledge both the noetic effects of the fall, and the reality of God’s common grace.

This book is not one for the casual reader, since its conceptual analysis is quite high. Similarly, Oliphint’s controversial evaluation of Aquinas' thought means this book will likely be of most interest to the student who wants to explore a biblical epistemology in some detail, rather than the layperson interested in church history. Those who are already familiar with Aquinas may find food for thought in Oliphint’s thoughtful critique, even if you find his approach ultimately misses the mark.

References

[1] For a helpful introduction to the presuppositional approach you might like to consider John Frame’s Apologetics: A Justification of Christian Belief (previously published under the title Apologetics to the Glory of God).

[2] For those interested in a more detailed assessment of the accuracy of Oliphint’s portrayal of Aquinas, Richard Muller’s review is worth reading.

K Scott Oliphint.Thomas Aquinas (Great Thinkers). P&R, 2017. 168pp.

© 2019 Isaac Pain