Stephen Fry and God

Stephen Fry has caused a bit of a stir with his comments to Gay Byrne on the kind of god he does not believe in. As is his habit, Fry did not hold back:

How dare you? How dare you create a world to which there is such misery that is not our fault. It's not right, it's utterly, utterly evil. Why should I respect a capricious, mean-minded, stupid God who creates a world that is so full of injustice and pain. That's what I would say.

Now, if I died and it was Pluto, Hades, and if it was the 12 Greek gods then I would have more truck with it, because the Greeks didn't pretend to not be human in their appetites, in their capriciousness, and in their unreasonableness … they didn't present themselves as being all-seeing, all-wise, all-kind, all-beneficent, because the god that created this universe, if it was created by god, is quite clearly a maniac … utter maniac, totally selfish.

We have to spend our life on our knees thanking him? What kind of god would do that?

It's worth listening to the clip yourself, if you have not already done so.

Before engaging in the substance, there are a few things worth noting about this as communication. First, it is curious either that Byrne should be surprised by this 'outburst' or that Fry should be surprised by the response. Fry's comments are just what you would expect if you had done your research well (or even watched a couple of episodes of QI) and when you call the god that many people claim to believe in "capricious, mean-minded, stupid … an utter maniac, totally selfish" you would have to be living on another planet to imagine this will not cause a stir of some sort.

But the second thing worth noting is that Fry's comments are expressed in highly emotive terms. Fry cites Bertrand Russell as one of his rational forebears in this atheist tradition, and a good many atheists have welcomed his comments as some kind of knock-down logical argument to which religion has no response. When I was discussing this on local radio with a humanist, his main comment was "I am glad people are asking questions – that's what I want people to do." Curiously, not many are asking questions about Fry's own comments, for good reason: his style does not invite questioning. It turns out, for example, that the eyeball-burrowing worm he mentions does not in fact exist. Earlier in the programme, Fry had mentioned that he stole a jacket as a teenager and lived the high life off credit cards he had found in the pocket for three months.

"He gave as his answer as to how he got away with it for three months, part of the reason was he is a very big guy, and secondly he said, 'because I had an aura of authority about it'." said Gay.

"He had this voice, this very upper class British voice. He said, 'When I issue a statement it stays issued and you'd be a very brave person to take me on'."

The popularity of Fry's approach is that it is emotive and closes questions down, rather than that it is rational and opens questions up, which is somewhat ironic.

scepticism is easy ... offering a reflective defence on any issue requires a lot more work

Thirdly, we need to remember that scepticism is easy — that's why so many stand-up comics deal with scepticism and cynicism in their material. Being critical of something is usually quick and easy; offering a reflective defence on any issue requires a lot more work — and usually depends on the kind of patience and trust within the conversation which is hard to establish in any broadcast medium.

In terms of a the substance of Fry's objection, there are a number of inter-related things to say. First, we have to admit there is no quick and easy philosophical response to the problem of suffering. That applies to Fry's comments as much as it does to the standard Christian arguments. Fry is not offering a solution to the problem of suffering; when you abolish God, you do not abolish the problem of pain. In effect, he is saying "There is no solution, so just get on with it." As David Robertson responds:

If you take God out of the equation you still have the suffering, pain and apparent meaninglessness. Evolution still provides you with the worm that burrows through children's eyes. What's your answer and solution – apart from suck it up and see?

On the other hand, some of the classic Christian responses don't cut the mustard either. The popular version of the classic 'free will defence' says that a suffering world is a necessary consequence of God giving humanity free will. This does offer one reply to Fry's comment that God "could easily" have created a world without suffering; it looks about as easy as making a square circle. But an obvious response to the free will defence is: well, was it really worth it? Is my human dignity really worth giving someone the ability to torture another human being and burn them alive, let alone the suffering caused by natural disasters? Besides, when someone is in a place of suffering themselves, the last thing they need is a philosophical defence of God.

A god who does not share in the suffering of the world is not a god worth believing in

This relates to the second main issue: the god that Fry describes is not the God that most Christians believe in. This God does not sit aloof from a suffering world, nor is the world the way God intended it to be. It is not as straightforward as saying that human sin causes tsunamis, but Scripture is clear that human sin does destroy relationships in marriage (Genesis 3), in families (Genesis 4) and across society (Genesis 8-11). It harms the earth (Hosea 4:3), and in some mysterious sense the whole of creation is "in bondage to decay" (Romans 8:21). And God's response to this is one of both justice and compassion – to the point of stepping into this troubled world. A god who does not share in the suffering of the world is not a god worth believing in.

It is striking that this God allows, even encourages, questioning. Human protestations against God occupy a large part of the Psalms, and the entirety of the book of Job. And contrary to Fry's assertion, God isn't interested in people grovelling in gratitude at his unquestioning power. In Psalm 95, God's power evokes celebration, not grovelling, and bowing down in worship is a response to his tender care, not his omnipotence.

Thirdly, if there is no god, where does Fry get his sense of justice and injustice from? On what grounds does he make a judgement about things being 'evil', which is a moral, not a rational, category? The evangelist Michael Green's first experience of university missions was at the London School of Economics – a hotbed of left-wing liberalism – in the 1960s. He leapt onto the stage in front of a group of sceptical atheists and called out 'Why are you lot revolting?' He was asking where their sense of right and wrong and injustice came from, if not from God. "God has left his footprints in the heart of humanity" (see Ecclesiastes 3:11).

A much more consistent position for an atheist is that expounded by Richard Dawkins:

In a universe of electrons and selfish genes, blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won't find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference.

This is a much more coherent position – but I suspect Fry is very well aware that it is not very appealing, and does not look like very good PR. Nor does it actually answer the question he raises; instead, it declares the question itself meaningless. In that sense, the questions that Fry raises are actually close to questions of faith, not questions of unbelief.

This leads on to a related question: Where does Fry find hope for an end to suffering, or for any sense of justice and accountability? Will those who burn alive a Jordanian pilot ever be held to account? Or (more pertinently for an atheist) will those responsible for Stalin's killing of 20 million people ever face justice? It might be that suggesting there is a god who sees all this and will hold people to account in judgement is an inadequate answer. But it starts to look like the least worse option when the alternative is that there is no-one who sees and justice will never be done.

The Christian vision for the world is that one day there will be an end to suffering, and there will be an account given of all injustice and oppression – that, through the self-giving suffering of God, evil will in some mysterious way be brought to an end. This can still be dismissed as wishful thinking, and I should make clear that I don't believe this because it would be nice – I believe it because I think it is true!

The Christian vision for the world is that one day there will be an end to suffering, and there will be an account given of all injustice and oppression – that, through the self-giving suffering of God, evil will in some mysterious way be brought to an end. This can still be dismissed as wishful thinking, and I should make clear that I don't believe this because it would be nice – I believe it because I think it is true!

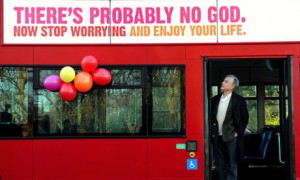

There is a real challenge here for atheists to offer a credible, hopeful alternative. It is all very well telling wealthy Londoners to "stop worrying and enjoy life", but that doesn't cut much ice with the vast majority of humanity who have plenty to worry about and many fewer resources with which to enjoy life.

If God were to make a world without suffering, what would it look like?

The final question Fry raises is that of human action. If God were to make a world without suffering, what would it look like? What would God intervene to prevent? Tsunamis and earthquakes are one thing; but what kinds of human action would God prevent? I am sure we would be happy to see an end to war, murder, rape and abuse. But what about rivalry and jealousy, which has so often inhibited scientific development? What about lack of cooperation and sharing of information that could bring real relief to human suffering? What about financial inequality, which is perhaps the greatest threat to global well-being? Stephen Fry's net worth has been estimated at around £20m, though anyone with a net worth of £500,000 is in the richest 1% of the world who own half the world's capital assets. Beyond all that, what would this omnipotent God do about the sheer indifference of most humanity to the suffering of others? For many of us, God's lack of action (for the moment) looks like a mercy – an opportunity to 'redeem our lives'.

These questions have a connection with the free will defence. But they have sharper resonance with the issue of human responsibility. As John Goldingay once said:

The problem of theodicy is not the justification of a holy God in the face of suffering humanity, but the justification of sinful humanity in the face of a holy God.

Fry claims that "the moment you banish [God] life becomes simpler, purer, cleaner". The testimony of history hardly supports such a claim.

In the same week that Stephen Fry was railing against worms that caused suffering, it was announced that another similar affliction was coming to an end – that of the guinea worm.

In the same week that Stephen Fry was railing against worms that caused suffering, it was announced that another similar affliction was coming to an end – that of the guinea worm.

A devastating tropical disease should be eradicated within three years, says the former American president leading the fight against it. There were 3.5 million cases of guinea worm worldwide when Jimmy Carter's organisation started tackling the disease in 1986. Now there are just 126 cases globally – many of them in South Sudan and Mali.

Former US President Jimmy Carter has been motivated to this work by his evangelical faith – faith in the god that Fry appears to reject. The Carter Foundation's next goal is to eliminate river blindness. Perhaps his legacy is the best answer to Fry's complaint.

© 2015 Ian Paul

| For another response to Stephen Fry's comments, see: Justin Brierley's blog 'What Stephen Fry could learn from Oscar Wilde'. Ed. |