How to Survive the Apocalypse - a review

"The world is going to hell" – so say Robert Joustra and Alissa Wilkinson at the beginning of this book. They’re not talking about the daily turmoil we see on the news, but rather the TV shows we watch to relax.

How to Survive the Apocalypse is a multifaceted analysis of what our culture’s love of dystopian fiction reveals about our current socio-political environment. To do this they draw extensively upon Catholic philosopher Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age, making use of Taylor’s terminology throughout.[1]

And so for Joustra and Wilkinson our current age is secular not so much as it denies all religious belief, but rather that it is an age of contested belief. Believers just as much as non-believers inhabit this secular age. The book’s ultimate aim, given at the close of the book, is to answer the question:

Who are we and how do we live together after the 'apocalyptic' deconstruction (or destruction) of our systems, our institutions, and our inheritance?

In order to answer this question Joustra and Wilkinson make use of dystopian and post-apocalyptic TV shows to see what our society believes about the individual and institutions. Their methodology seeks to identify what is good and what is broken within society today, with the hope of maximising one and healing the other. Each chapter uses a couple of films or TV series to demonstrate and support Taylor’s analysis of our age. In a footnote early on, Joustra and Wilkinson describe their book as "an accessible, applied introduction to Taylor’s work", but nonetheless some prior appreciation of Taylor’s work is probably required. Since few outside of academia will have read Taylor’s 900-page tome, at times perhaps too much was assumed by the authors.

authenticity can never be achieved without moral horizons outside of the individual self

The book starts with a brief history of apocalyptic literature and ideas. After this the analysis of TV shows begins by considering how the Cylons of Battlestar Galactica speak of our culture’s search for identity, recognition and authenticity from within the individual. However, analysis of the anti-heroes in Breaking Bad, House of Cards, and Mad Men shows that this authenticity can never be achieved without moral horizons outside of the individual self. The hopeless end that all anti-heroes come to is a direct result of following their own individually defined values and trying to escape the inescapable moral horizons that come from outside of us.

The film Her is used to argue that society’s shift towards authenticity does not by necessity have to lead towards a hyper-individualism. This chapter provides a fascinating analysis of identity politics, and how the law is now called upon to legitimate us as unique individuals.

Next, Game of Thrones is brought in to explore the idea of subjectivism, after which The Walking Dead is used to show the complexity of the process by which society makes choices due to the extreme diversity of the age. The authors then consider how political thriller Scandal demonstrates the way art no longer connects with shared beliefs but rather shared experiences. This in particular offers a helpful analysis for those wanting to communicate effectively into our apocalyptic age. The idea, again being drawn from Taylor, is that our current age is shaped more by Romanticism than the Enlightenment. Therefore, appeals to reason – rather than to a shared experience or story – fall on deaf ears. The penultimate chapter looks at The Hunger Games and shows our deep distrust of institutions, and the danger of what Sociologist Max Weber called "the iron cage", a loss of freedom brought about by increasing bureaucratic control over people's lives.

our current age is shaped more by Romanticism than the Enlightenment

The final chapter uses the prophet Daniel as an example for us to follow. Daniel, like us, lived in a post-apocalyptic age – but he didn’t sit idle. Rather, he was on Babylon’s side. The conclusion? We are currently living in apocalyptic times, in a secular age, but with this comes some good news: Christians can engage, as they always have, in the public work of realising the best of the motivating ideals of this age.

The authors conclude:

We can sing the Lord’s song, but we don’t build the Lord’s city. And so the politics of apocalypse is a religious pragmatism – not defeatism, just recognition that the tensions of this age, as ages past and ages to come, can’t be overcome, but only managed.

Joustra and Wilkinson have provided us with a good example of how to read and engage with popular culture in a very thoughtful way. Rather than offering easy answers and quick tips on how to use popular TV shows to engage non-believing friends, this book provides a rallying call for Christians to shape society and its institutions for its good.

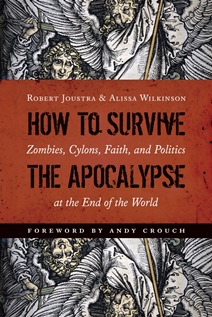

Book Title: How to Survive the Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, Faith, and Politics at the End of the World

Authors: Robert Joustra and Alissa Wilkinson

Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans

Publication Date: 2016

Pages: 206

Price: £10.99

Buy from Amazon.co.uk. Buy from Amazon.com.

References

[1] Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Harvard University Press, 2007). For a more detailed summary and analysis of Taylor’s A Secular Age, Joustra and Wilkinson suggest James K.A. Smith, How (Not) to Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor (Eerdmans, 2014).

© 2016 Isaac Pain