Apologetics in 3D

This paper – a contribution to the field of metapologetics [1] – advances a holistic definition of apologetics [2] as:

- The art of persuasively advocating Christian spirituality across spiritualities, through the responsible use of classical rhetoric, as being objectively true, beautiful and good.

After contrasting this definition of apologetics with some standard definitions and commenting upon the evolving role of worldview analysis within apologetics, I will unpack all three clauses of the above definition before arguing that it captures Paul’s approach to apologetics as exemplified by his Athenian mission.

On Standard Definitions of Apologetics

A key advantage of my definition of apologetics is that it avoids narrow intellectualism without downplaying the importance of the intellect. The discipline of Christian apologetics is commonly defined in purely academic [3] terms. For example:

- R.C. Sproul, John Gerstner and Arthur Lindsey state that ‘Apologetics is the reasoned defence of the Christian religion.’[4]

- C. Stephen Evans defines apologetics as ‘The rational defence of Christian faith.’[5]

- Winfried Corduan says that ‘The defence of the truth of Christianity is called apologetics.’[6]

- James E. Taylor writes that ‘Christian apologists defend the truth of Christian claims … they try to show that it is reasonable to believe what Christians believe.’[7]

- Francis J. Beckwith explains that ‘responding to … challenges and offering reasons for one’s faith is called apologetics.’[8]

- John Frame describes apologetics as a matter of three inter-related elements: ‘(1) proof, rational confirmation for faith; (2) defence, replies to criticisms; and (3) offense, bringing criticisms against non-Christian ideas.’[9]

- William Lane Craig writes that: ‘Apologetics (from the Greek apologia: defence) is that branch of Christian theology which seeks to provide rational justification for the truth claims of the Christian faith.’[10]

- Norman L. Geisler and Patrick Zukeran likewise note that ‘Apologetics comes from the Greek word apologia, which means a defence’ and write of the apologist as one who ‘uses reason and evidence to present a rational defence of the Christian faith.’[11]

- H. Wayne House and Dennis W. Jowers affirm that ‘Apologetics … is a defence (apologia) of one’s position or worldview as a means of establishing its validity and integrity. It is an attempt to establish the truth of the matter and to present a convincing argument in support of it.’[12]

This isn’t to say that everyone who gives an academic definition of apologetics necessarily does apologetics in a merely academic way (for example, Craig uses existential concerns in his apologetic[13]), or that they don’t qualify their definitions (e.g. Geisler and Zukeran subtitle their book ‘A Caring Approach to Dealing with Doubters’, etc[14]). However, such disjunctions between apologetic definition and practice underline the need to revisit the definition.

While the academic definitions of apologetics given by Sproul et al are technically correct, they nevertheless short-change our understanding (and thereby our practice) of apologetics. To define an apologist as a person who ‘uses reason and evidence to present a rational defence of the Christian faith’ is rather like defining a chef as ‘someone who prepares edible ingredients to be eaten’. Neither definition is exactly wrong, but they are both thin and misleading. They are, we might say, necessary but insufficient descriptions. How the chef prepares her ingredients is at least as important as the mere fact that she prepares them. Likewise, Gregory P. Koukl reminds us that ‘It’s not enough for followers of Christ to have accurately informed minds. They also need an artful method. They need to combine their knowledge with wisdom and diplomacy.’[15]

It seems to me that in any genuine incidence of apologetics what is happening is an attempt to persuade someone, not merely to change their mind, but to exchange their non-Christian ‘way of life’ for a Christian ‘way of life’ (cf. Acts 26:28).[16] In other words, apologetics is an attempt to persuade people to exchange their non-Christian spirituality for a Christ-centred spirituality. Hence, with Francis A. Schaeffer:

I am only interested in an apologetic that leads in two directions, and the one is to lead people to Christ, as Saviour, and the other is that after they are Christians, for them to realize the lordship of Christ in the whole of life… if Christianity is truth, it ought to touch on the whole of life… Christianity must never be reduced merely to an intellectual system… After all, if God is there, it isn’t just an answer to an intellectual question… we’re called upon to adore him, to be in relationship to him, and, incidentally, to obey him.[17]

Christianity includes but isn’t limited to a set of beliefs.[18] Likewise, persuasion includes but isn’t limited to intellectual persuasion. As Douglas Groothuis observes: ‘Christianity makes claims on the entire personality; accepting it as true is not a matter of mere intellectual assent, but of embarking on a new venture in life.’[19] Groothuis therefore defines apologetics in more holistic terms as ‘defending and advocating Christian theism’,[20] adding that ‘Christ-like apologetics labors to communicate the truth in love and with wisdom’.[21] The definition of apologetics I am offering extends this holistic shift in emphasis to its logical conclusion.

Worldviews & Spirituality

Another benefit of the definition of apologetics I am offering is that it incorporates some sound advice, drawn here by Doug Powell from Acts 17:22-34:

Paul found common ground in the fact that his audience believed in some form of religion. The problem, according to Paul, was that they believed in something false, not that they believed in nothing. They had a religious worldview, but it was full of holes. Knowing the egregious flaws in their religious system, he made a case for Christianity…[22]

Powell draws attention to the scriptural wisdom of building dialogue upon common ground and to the underlying importance to apologetics of worldview analysis – that is, of a capacity to categorise, understand and critically engage with people’s differing sets of answers to the basic philosophical questions.

Schaeffer likewise argued that a critique of incoherence and falsehood in non-Christian worldviews, on the basis of shared epistemological standards, is a methodologically wise pre-amble to offering the Christian worldview as a plausible alternative. He memorably called this process ‘taking the roof off’:

Every person is somewhere along the line between the real world and the logical conclusion of his or her non-Christian presuppositions. Every person has the pull of two consistencies, the pull towards the real world and the pull towards the logic of his system… To have to choose between one consistency or the other is a real damnation for man. The more logical a man who holds a non-Christian position is to his own presuppositions, the further he is from the real world; and the nearer he is to the real world, the more illogical he is to his presuppositions… the first consideration in our apologetics for modern man … is to find the place where his tension exists… when we have discovered, as well as we can, a person’s point of tension, the next step is to push him towards the logical conclusion of his presuppositions… every man has built a roof over his head to shield himself at the point of tension. At the point of tension the person is not in a place of consistency in his system, and the roof is built as a protection against the blows of the real world, both internal and external… the Christian, lovingly, must remove the shelter and allow the truth of the external world and of what man is, to beat upon him. When the roof is off, each man must stand naked and wounded before the truth of what is. The truth that we let in first is not a dogmatic statement of the truth of the Scriptures, but the truth of the external world and the truth of what man himself is. This is what shows him his need. The Scriptures then show him the real nature of his lostness and the answer to it.[23]

I agree that apologists should try to use common ground to lead the non-Christian into a discovery of cognitive dissonance [24] inherent within their non-Christian worldview, revealing a felt need to which the Christian worldview can be addressed as a to-be-desired intellectual and existential resolution. However, to follow this advice one must be able to compare and contrast the Christian worldview with relevant non-Christian worldviews (so that one can build upon commonalities whilst critiquing differences). Hence Kenneth D. Boa and Robert M. Bowman Jr. begin their textbook on apologetics by framing the issue at hand in terms of worldviews:

How to relate the Christian worldview to a non-Christian world has been the dilemma of Christian spokespersons since the apostle Paul addressed the Stoic and Epicurean philosophers in Athens.[25]

To this end, apologists have proposed various definitions of ‘worldview’ (as well as various classificatory systems through which to understand how different worldviews provide mutually incompatible perspectives on reality[26]). Interestingly, the trajectory of these discussions has been to move from a narrowly academic definition of a ‘worldview’ to more holistic descriptions. This trend is exemplified by the fact that while the first edition of James W. Sire’s classic text The Universe Next Door (IVP, 1976) defined a worldview as simply ‘a set of presuppositions (assumptions which may be true, partially true or entirely false) which we hold (consciously or subconsciously, consistently or inconsistently) about the basic makeup of our world', the 5th edition thereof (2009) defined a worldview as:

a commitment, a fundamental orientation of the heart, that can be expressed as a story or in a set of presuppositions (assumptions which may be true, partially true or entirely false) which we hold (consciously or subconsciously, consistently or inconsistently) about the basic constitution of reality, and that provides the foundation on which we live and move and have our being.[27]

Powell’s advice about worldview apologetics, helpful and scripturally based as it is, nevertheless reflects the one-dimensional, academic approach seen in many definitions of apologetics. D.A. Carson is right to observe that the challenge of thinking about apologetics in worldview terms ‘is not primarily to think in philosophical categories, but to make it clear that closing with Jesus has content … and is all-embracing (it affects conduct, relationships, values, priorities).’[28]

Boa and Bowman comment:

Classical apologists seek to show that the Christian worldview is rational or reasonable and therefore worthy of belief… This focus is widely perceived as a weakness in the classical approach because it overlooks the personal nonrational factors that contribute to a person’s knowledge and beliefs… Commitment to ultimate philosophical perspectives is not merely intellectual; it is also influenced by emotional and volitional factors.[29]

Much of the valuable work done in recent decades by Christian scholars on the issue of worldviews[30] likewise tends to focus attention on the academic dimension of apologetics, at least where ‘worldview’ is understood as something like ‘a set of beliefs about the most important issues in life.’[31] For although Christianity is a worldview in this sense, there’s more to Christianity than that. As Robert L. Reymond affirms:

Christian apologetics should not only be concerned with correct epistemological method but at bottom should also be evangelistic and kērygmatic… the Christian apologist will … seek to present persuasively the Christian faith in all of its wholeness and beauty…[32]

The gospel addresses itself to the whole person, and Christian apologetics must therefore be grounded in and addressed to a Christian understanding of human nature. On this basis we should recognize with Alister McGrath how ‘apologetics must ensure that the relevance of the Christian gospel to the human heart, as well as the human mind, is fully explained and explored.’[33] McGrath consequently presents a more holistic definition of apologetics than Sproul et al, explaining that apologetics is:

the field of Christian thought that focuses on the justification of the core themes of the Christian faith and its effective communication… Apologetics celebrates and proclaims the intellectual solidity, the imaginative richness, and the spiritual depth of the gospel in ways that can connect with our culture.[34]

Nor should we leave out the relevance of the gospel to human action in the world. Let’s be clear: I am not proposing that apologetics should advocate Christianity as appealing to the desires of the heart and / or the requirements of practical living rather than appealing to rationality. C.S. Lewis famously observed that ‘One of the great difficulties [in apologetics] is to keep before the audience’s mind the question of Truth. They always think you are recommending Christianity not because it is true but because it is good.’[35] Nevertheless, in apologetics we should appeal to the whole person (heart, hands and mind). I therefore wholeheartedly endorse Gregory E. Ganssle’s comment that in apologetics ‘Our hope is to bring facets of the richness of the gospel to bear on the lives, beliefs, values, and identities of lost human beings.’[36]

On these grounds I have much sympathy with Sire’s move to a more holistic definition of ‘worldview’. Indeed, Sire’s evolving definition is approaching what I would consider a generic definition of ‘spirituality’, i.e. ‘worldview beliefs married to attitudes that lead to actions’. This tripartite understanding of ‘spirituality’ (upon which my definition of apologetics is built) retains the precision of Sire’s academic definition of ‘worldview’ without rejecting the holistic insights embraced by Sire’s more recent (and unwieldy) formulation. Thus, although I concur with the advice about worldviews given by Powell – and those who offer essentially the same advice about their importance [37] (often with reference to the same scriptural source [38]) – I believe this wisdom can be fruitfully subsumed within a holistic understanding of apologetics (one that focuses attention upon the ‘all-embracing’ nature of the gospel) as:

- The art of persuasively advocating Christian spirituality across spiritualities, through the responsible use of classical rhetoric, as being objectively true, beautiful and good.

As a foundational term in this definition, ‘spirituality’ bears a closer look.

Defining ‘Spirituality’

While some people assume that spirituality should involve God, plenty of people (e.g. Buddhists and Secular Humanists) engage in spirituality without any reference to God.[39] Alexander W. Astin et al state that ‘Spirituality points to our inner, subjective life, as contrasted with the objective domain of observable behaviour…’[40] However, many people associate ‘spirituality’ with certain spiritual practices (e.g. prayer, yoga or recycling). Of course, this implies a distinction between spiritual and non-spiritual activities that Christian spirituality, for one, rejects (cf. Romans 1:12; Colossians 1:10 & 3:23). Clearly, a general definition of spirituality must avoid prescriptions about the specific content of spirituality (whether ‘internal’ or ‘external’); which means that we must focus instead upon the general structure of spirituality. I therefore propose the following general definition of spirituality:

- Spirituality concerns how humans relate to reality – to themselves, to each other, to the world around them and (most importantly) to ultimate reality – via their worldview beliefs, concomitant attitudes and subsequent behaviour.

In other words, spirituality is about how one relates to reality through the combination of one’s head, heart and hands.

The entirely general definition of spirituality given above is consistent with the Biblical understanding of how humans learn, found in Deuteronomy 31:10-12:

Then Moses commanded them: ‘At the end of every seven years … when all Israel comes to appear before the LORD your God at the place he will choose, you shall read this law before them in their hearing. Assemble the people – men, women and children, and the foreigners residing in your towns – so they can listen and learn to fear [i.e. respect] the LORD your God and follow carefully all the words of this law.’ (my emphasis)[41]

Educationalist Perry G. Downs comments:

Moses states that he wanted the people to learn to fear the Lord. The word translated ‘learn’ (lamath) is the most common Hebrew word for learning. It implies a subjective assimilation of the truth being learned, an integration of the truth into life. Learning was to be demonstrated in two ways, by a change of attitude and by a change in action.[42]

When listening to the word of the Lord is combined with a positive attitude of reverent ‘fear’ of the Lord the people will follow the law. Likewise, apologetics isn’t just about getting people to change their minds, but their fundamental spiritual allegiance; and spirituality is a matter of worldview beliefs married to attitudes that sustain actions.[43]

A person’s actions are ‘spiritual’ insofar as they are an organic outworking of their beliefsabout reality and their attitudes (whether positive or negative) towards what they believe about reality. Different spiritualities embody different answers to the question of how people can best relate to reality (or how they ought to relate to reality). Spiritualities make distinctive and mutually contradictory knowledge claims (even those that incoherently repudiate the concepts of truth and knowledge).[44] There is thus an integral relationship between spirituality and worldview: the answers we give to fundamental worldview questions partially determine the nature of our spirituality. Every mature, properly functioning human being has a worldview:

By God’s design, people as thinking, feeling, and willing beings cannot function without a governing frame of reference to help them understand life and find their way in the world. That is exactly what a worldview is and does… All persons as persons have some kind of worldview outlook whether they realize it, or can explain it, or not.[45]

Of course, the worldview beliefs a person holds is far from being a narrowly intellectual matter. Hence David Naugle discusses how life ‘proceeds “cardioptically” out of a vision of the heart with its deeply embedded ideas, affections, choices, and object of worship.’[46] Sire comments that ‘This notion would be easier to grasp if the word heart bore in today’s world the weight it bears in Scripture. The biblical concept includes the notions of wisdom (Proverbs 2:10), emotion (Exodus 4:14; Jn. 14:1), desire and will (1 Chronicles 29:18), spirituality (Acts 8:21) and intellect (Romans 1:21).’[47]

Glen Schultz explains that: ‘At the foundation of a person’s life, we find his beliefs. These beliefs shape his values, and his values drive his actions.’[48] What we believe about the answers to the fundamental questions (whether consciously or unconsciously) affects our attitudes, decisions and actions in life. That is, our worldview is the foundation of our spirituality (cf. Romans 12:2; 2 Corinthians 10:5). A belief is someone’s view of how reality is. According to J.P. Moreland: ‘A belief’s impact on behaviour is a function of three of the belief’s traits: its content, strength, and centrality.’[49] The content of a belief is what is believed. Reality is indifferent to what we believe about it, or how sincere our beliefs are. Our beliefs about reality are true or false depending upon the way reality actually is.[50] A belief’s strength is ‘the degree to which you are convinced the belief is true... The more certain you are of a belief… the more you rely on it as a basis for action.’[51] The centrality of a belief ‘is the degree of importance the belief plays in your entire set of beliefs, that is, in your worldview.’[52] The more central a belief is in our noetic structure, the greater the effect would be on one’s spirituality were the belief in question to be revised or abandoned: ‘In sum, the content, strength and centrality of a person’s beliefs play a powerful role in determining the person’s character and behaviour.’[53]

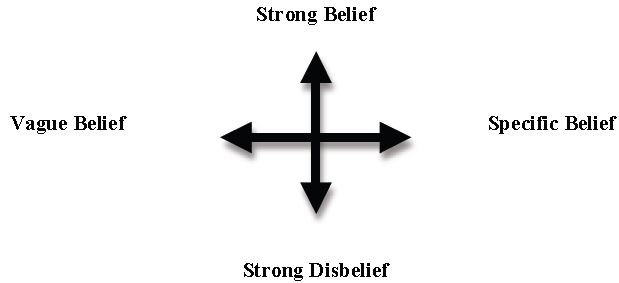

Following James W. Sire [54], we can plot beliefs on a spectrum with two axes measuring strength and content, from strong belief to strong disbelief, and from vague belief to specific belief. Beliefs can be simultaneously more or less vague and more or less strong components of our noetic structure:

An ancient Greek erecting an altar ‘to an unknown god’ may believe very strongly that such a deity exists whilst necessarily having a vague idea about its nature. The Christian may believe strongly that God is Trinitarian, whilst having only the vaguest idea of how God is Trinitarian.[55]

The content, strength and centrality of what we believe is and isn’t true about reality affects what attitudes we take towards reality and what practices our spirituality includes (e.g. no-one can pray to a God they are certain doesn’t exist, while someone certain that ‘some kind’ of a deity exists may lack any confidence that he is the sort of deity that would attend to their prayers):

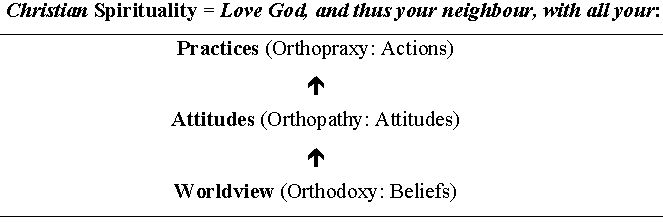

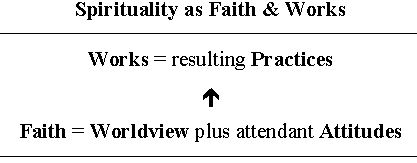

- Our worldview beliefs ground our spiritual attitudes which thereby jointly sustain our spiritual practices.

All spiritualities can be analyzed in terms of this three-part generic structure.[56]

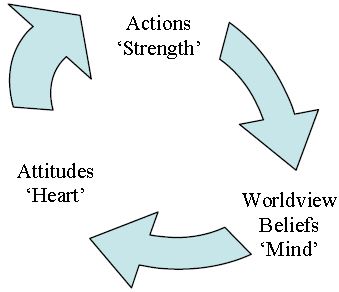

As suggested by its earliest description as ‘The Way’ (cf. John 14:6, Acts 11:26 & 22:4), Christianity is a way of life (a spirituality) centred upon knowing and following Jesus Christ – who is ‘the way, the truth and the life’ (John 14:6). Jesus calls upon us to enter into true spirituality through a strong, central belief in a specific God (as revealed in and through his own person). The following diagram represents the resultant inner structure of Christian spirituality, as defined by Jesus, Peter and Paul:

The tripartite understanding of spirituality as a matter of orthodoxy, orthopraxy and orthopathy should have a familiar ring to those acquainted with Jesus’ response to a teacher of the law about the requirement to ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart [i.e. your will, your attitudes]... and with all your mind [including your worldview], and with all your strength [i.e. your actions]’ (Mark 12:30, my italics).[57] The same structure is seen in the crowd’s response to Peter at Pentecost:

When the people heard this [i.e. when they gave mental assent to the truth-claims about Jesus and his resurrection], they were cut to the heart [their attitude was one of positive response] and said to Peter and the other apostles, ‘Brothers, what shall we do?’ [they acted in response]. (Acts 2:37)

1 Peter 3:15 urges Christians:

In your hearts [broadly construed as a matter of both mind and attitude] set apart Christ as Lord and always be prepared to give [i.e. this is something one must be prepared to do] an answer for the reason [i.e. an apologia] for the hope that you have [in your heart]. But do this with [a heart attitude of] gentleness and respect. (my emphasis)[58]

Paul likewise advises the Colossians:

And above all these put on love, which binds everything together in perfect harmony. And let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts [‘all your heart’], to which indeed you were called in one body. And be thankful. Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, teaching and admonishing one another in all wisdom [‘all your mind’], singing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, with thankfulness in your hearts to God. And whatever you do [‘all your strength’], in word or deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him. (Colossians. 3:14-17, ESV, my emphasis)[59]

The New Testament letter of James argues that true faith naturally results in faith-filled actions (i.e. works):

What good is it, my brothers, if a man claims to have faith but has no deeds? Can such faith save him? Suppose a brother or sister is without clothes and daily food. If one of you says to him, ‘Go, I wish you well; keep warm and well fed,’ but does nothing about his physical needs, what good is it? In the same way, faith by itself, if it is not accompanied by action, is dead. But someone will say, ‘You have faith; I have deeds.’ Show me your faith without deeds, and I will show you my faith by what I do. You believe that there is one God. Good! Even the demons believe that – and shudder. (James 2:14-19)

Any spirituality can be understood in terms of attitudes based upon worldview beliefs – the combination of belief that with belief in which constitutes ‘faith’ – (which corresponds with the broader definition of ‘the heart’ used by Naugle and Sire[60]) that in turn jointly result in various spiritual actions (i.e. ‘works’).

As C.E.M. Joad affirms:

action always presupposes an attitude of mind from which it springs, an attitude which, explicit when the action is first embarked upon, is unconscious by the time it has become an habitual and well established course of conduct. When I act in a certain manner towards anything, I recognize by implication that it possesses those characteristics which make my conduct appropriate… If I cannot find good grounds for my beliefs, I shall certainly not persuade myself to act in conformity to them; thus, if I do not accept the attribution of personality to God I shall not succeed in inducing myself to act towards him as if he were a person… Thought, in other words, precedes action in the religious as well as other spheres, and the practical significance of the precepts of religion is not separable from the theoretical content from which they derive. It is, then, because my intellect is on the whole convinced that I made such shift as I can to live conformably with its dictates… intellect, faith, will and desire … co-operate to produce religious belief and the endeavour to act conformably with it.[61]

That is, spiritual practices are not only the result of our spiritual beliefs and their attendant attitudes, but also constitute additional openings to the object of faith (whether real or imagined), openings that re-enforce our initial beliefs and attitudes. Spiritual practices are not just the natural, practical outworking of faith, but also positive aids to faith. Spiritual practices are part of a spiritual ‘positive feedback loop’ (this is obvious when one thinks of practices such as prayer; but spiritual practice encompasses the whole of life insofar as it is lived out of our spiritual beliefs and attitudes). Our attitudes not only reflect what we believe, they can restrict the range of truth-claims we will even actively consider for belief. In light of this fact, it would be appropriate to represent spirituality as a dynamic loop:

Apologetics is itself a spiritual practice that involves the whole person (cf. 1 Peter 3:15; 2 Corinthians 10:4-5; Colossians 4:5-6). For the true ambassador of Christ: ‘an accurately informed mind, an artful method [strength]; and character, an attractive manner [heart] – play a part in every effective involvement with a non-believer.’[62]

Elizabeth A. Dreyer and John B. Bennett comment that:

Much of [a person’s] worldview is inherited from family, education, society, relationships. But as adults, we have the opportunity to name, reflect on, and shape these values in freedom. No authentic spirituality is simply a ‘construct’ that we have mindlessly appropriated from the world around us – whether from a religion or our consumer culture. Nor is genuine spirituality coerced in any way…[63]

Hence we must distinguish between ‘intrinsic’ and ‘extrinsic’ spirituality. Intrinsic spirituality is self-consciously accepted and internalised by an agent as an end in itself (rather than as a pragmatic means to an end) and is hence far more transformative than an extrinsic spirituality that’s a matter of mere external conformity.[64] Sociologist Steve Fuller suggests that ‘most people rarely decide to believe anything in particular, simply because it is more convenient to move through a world already equipped with default beliefs. Active rejection takes work, passive acceptance does not.’[65] Nevertheless, personal integrity demands an intrinsic spirituality; for any spirituality that’s merely ‘extrinsic’ will produce cognitive dissonance (lending itself to Schaeffer’s process of ‘taking the roof off’).

How integrative or disintegrative one’s spirituality is depends in part upon whether it is an intrinsic or an extrinsic spirituality. However, it also depends upon the extent to which a) one’s spiritual practices cohere with and flow from one’s spiritual attitudes and the extent to which b) one’s spiritual attitudes stand in a positive or negative relationship to one’s worldview beliefs. A fully integrative spirituality is an intrinsic spirituality in which all one’s practices naturally flow from (and hence cohere with) a positive affective relationship with one’s worldview beliefs. A disintegrative spirituality, by contrast, is one in which dissonance is engendered by conflict within or between the three elements of spirituality (i.e. mind, heart and strength). For example, the person who believes that God exists but who reacts to this belief with an attitude of resentment and deliberate malfeasance will have a disintegrative spirituality. The tension generated by this lack of spiritual integration can be resolved either by removing (or repressing) the belief that God exists, or by changing the orientation of the heart. The danger in seeking spiritual integration is thus that we will resolve spiritual tension by aligning our beliefs with our actions and / or attitudes, rather than aligning our actions and / or attitudes with our beliefs, thereby flouting our epistemic responsibilities by prioritising personal comfort and convenience over truth (cf. Psalm 14:1 & 53:1).

With these distinctions in place we can state that the ideal goal of Christian apologetics is:

• A strong, central and epistemically virtuous self-conscious internalisation of a specifically Christian integrative spirituality.[66]

Intrinsic spiritual integration has no permanent value unless it is built upon the rock of truth (cf. Acts 17:24-29; Matthew 7:24-25). Nevertheless, the apologist should bear in mind the need to engage with people at the level of their spiritual attitudes and practices. This point can be better appreciated using categories derived from Aristotle’s The Art of Rhetoric, which Alister McGrath suggests ‘provides both a stimulus and a framework for more effective apologetics.’[67]

The Art of Rhetoric

Aristotle formally defines rhetoric as ‘the detection of the persuasive aspects of each matter,’[68] although in practice rhetoric obviously encompasses the principles of how best to communicate such objective observations to an audience: ‘For a speech is composed of three factors – the speaker, the subject and the listener – and it is to the last of these that its purpose is related.’[69] Aristotle explains that rhetoric encompasses three inter-related areas: ‘Of those proofs that are furnished through the speech there are three kinds. Some reside in the character of the speaker, some in a certain disposition of the audience and some in the speech itself, through its demonstrating or seeming to demonstrate.’[70] These three aspects of rhetoric are referred to by the Greek terms ethos, pathos and logos:

- Ethos – how the character and credibility of a speaker influences people to consider them to be believable

- Pathos – the use of emotional appeals to affect an audience’s judgment (e.g. through storytelling, or otherwise presenting the topic in a way that evokes strong affections in the audience)

- Logos – the use of reasoning to construct arguments

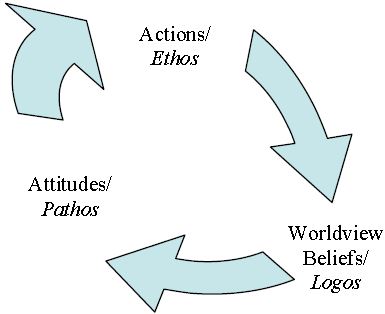

Ethos relates to the apologist’s character (a matter of both ‘heart’ and ‘strength’, but one known to the audience through the apologist’s actions) – cf. Galatians 5:22. Pathos relates to the affections of the apologist’s heart (communicated by word and deed). Logos relates to the apologist’s beliefs communicated by rational argumentation (‘mind’). Reason is part and parcel of rhetoric, not something to be contrasted with it.

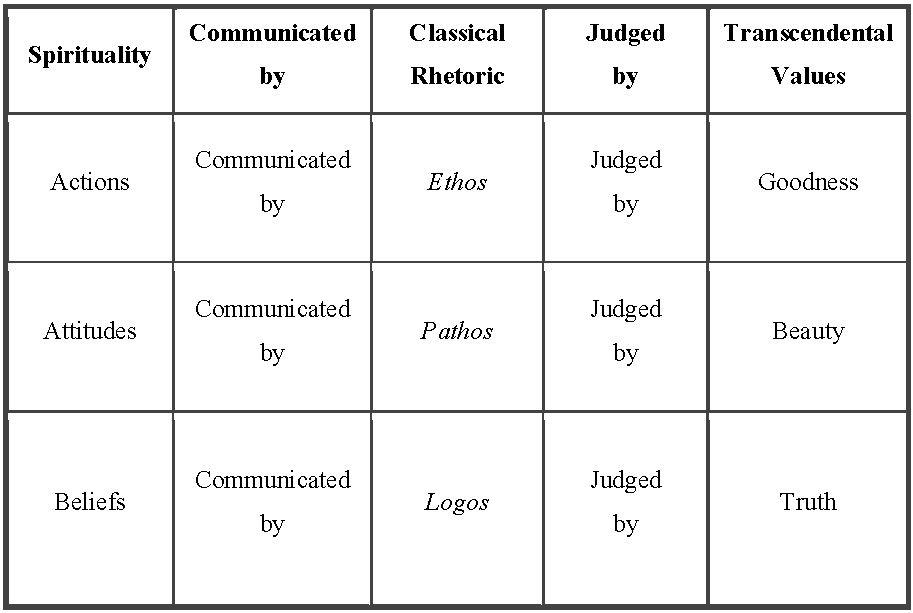

The three elements of rhetoric [71] correlate with the three elements of spirituality, as shown in the following diagram:

Thus we see that apologetics is a challenge to the apologist’s own spirituality, as well as the spirituality of the apologists’ partners in dialogue.

Transcendental Values

According to Cicero: ‘the eloquent speaker is he who in the forum and in the courts will speak in such a way as to achieve proof, delight and influence.’[72] These outcomes correspond not only to the rhetorical elements of ethos (persuasion by moral influence), pathos (persuasion by emotional delight) and logos (persuasion by proof), but to the traditional ‘transcendental’ values of truth (i.e. ‘proof’), beauty (i.e. ‘delight’) and goodness (i.e. ‘influence’). These properties are ‘transcendental’ because they are ‘properties found in absolutely everything that exists… Everything, in other words, is true, good and beautiful in some degree and in some respect.’[73] Peter Kreeft elaborates upon the traditional understanding of the transcendentals:

Truth is good and beautiful; goodness is true and beautiful; beauty is true and good. But there is an ontological (not temporal) order: it flows from Being to truth, truth to goodness, and goodness to beauty. Truth is judged by Being, goodness by truth, and beauty by goodness. The psychological order of our experience of them is the reverse: we are moved to goodness by its beauty, to truth by its goodness, and to Being by its truth.[74]

I have argued elsewhere [75] for the classical (and Biblical [76]) belief that truth, beauty and goodness are all objective values independent of our beliefs, desires and choices.[77] Given the inter-related nature of the transcendentals (i.e. truth is good and goodness is beautiful), the more commonly accepted objectivity of truth and goodness naturally carries over into discussions of aesthetic value. As atheist J.L. Mackie acknowledged: ‘much the same considerations apply to aesthetic and to moral values, and there would be at least some initial implausibility in a view that gave the one a different status from the other.’[78] Indeed, G.E. Moore argued that ‘the beautiful should be defined as that of which the admiring contemplation is good in itself... the question whether it is truly beautiful or not, depends upon the objective question whether the whole in question is or is not truly good.’[79] This move makes beauty objective by definition, given that moral values are objective.[80]

The co-incidence between rhetoric and the transcendentals is no coincidence – the transcendentals are precisely those categories by which all things are to be judged and are therefore the only ways in which any subject matter (including spirituality) could have an objectively persuasive aspect (truth, beauty, goodness) to be detected and communicated by the apologist’s rhetoric in each dimension (logos, pathos, ethos).

Consider former atheist A.N. Wilson’s acknowledgement that: ‘When I thought I was an atheist I would listen to the music of [Christian composer J.S.] Bach and realize that his perception of life was deeper, wiser, more rounded than my own….’[81] Bach’s beautiful music clearly played an apologetic function in Wilson’s life (one needn’t convince someone of the objectivity of beauty before beauty itself can play an apologetic function in illuminating their perception of reality). Peter Kreeft reports knowing ‘three ex-atheists who were swayed’ by Bach’s St. Matthew Passion [82] (two are philosophy professors and one a monk).[83] Hence the wise apologist will give some thought to the music played before their next public lecture. Likewise, we should take note when Peter Hitchens (brother of the late Christopher Hitchens) describes the role played in his return to faith by Rogier van der Weyden’s fifteenth-century painting of the last judgement:[84]

Another religious painting. Couldn’t these people think of anything else to depict? Still scoffing, I peered at the naked figures fleeing towards the pit of Hell, out of my usual faintly morbid interest in the alleged terrors of damnation. But this time I gasped, my mouth actually hanging open. These people did not appear remote or from the ancient past; they were my own generation. Because they were naked, they were not imprisoned in their own age by time-bound fashions… They were me, and the people I knew… I had a sudden strong sense of religion being a thing of the present day, not imprisoned under thick layers of time. A large catalogue of misdeeds, ranging from the embarrassing to the appalling, replayed themselves rapidly in my head. I had absolutely no doubt that I was among the damned, if there were any damned. And what if there were? How did I know there were not? I did not know.[85]

Attracted by artistic beauty, Hitchens encountered a spiritual truth about his own deficit of goodness. Hence the wise apologist will pay diligent attention not only to the words, but to the images (and film clips) in their next power-point presentation. As Alister McGrath writes:

The use of arguments … remains an integral part of Christian apologetics and must never be marginalized. However [older] Christian writers … placed a high value on biblical stories and images in teaching the faithful … both of which make a significant appeal to the human imagination. Anyone familiar with the history of Christian apologetics quickly realizes that both of these were used extensively as gateways to faith by earlier generations of apologists… We need to retrieve such older approaches to apologetics as we develop a balanced approach to the commendation and defence of the Christian faith…[86]

In the Footsteps of Paul

Paul’s Athenian mission, as recorded by Luke in Acts 17:16-34,[87] exemplifies the three-dimensional (beliefs, attitudes and actions) approach to Christian persuasion that I am calling apologetics ‘in 3D’. This observation is important because, at the very least, apologetic methodology shouldn’t run contrary to scriptural principles or examples. Moreover, the apologetic advice about worldview analysis that I have incorporated within my definition of apologetics is often drawn from, or illustrated with reference to, Luke’s ‘brief rendition of what must have been a much longer speech that Paul gave in Athens’ [88] before the Areopagus council.[89]

Paul was ‘a highly educated man’ [90] who was ‘well acquainted with pagan “high culture” – an acquaintance that, when sanctified, would thrust him, not Simon Peter, forward as the apostle to the Gentiles (Rom 11:13).’[91] Paul was a Tarsian from Cilicia (cf. Acts 9:30; 21:39; 22:3) where the famous Roman orator Cicero had been governor: ‘a centre of Hellenistic culture, claiming to rival Athens and Alexandria in its fame for learning. Paul was a child of two cultures.’[92] Tarsus was also the native city of several famous Stoic philosophers – including Antipater, Athenadorus, Nestor and Zeno.[93]

Paul’s deliberative address before the Areopagus follows classical standards far too closely for the match to be written off as an accident.[94] Indeed, taking account of Paul’s socio-rhetorical and educational background [95], as well as his evident ‘fluency in Greek and familiarity with Greek rhetoric,’[96] it seems plausible a priori to think he was familiar – at least indirectly – with Aristotle’s thinking on The Art of Rhetoric. In Colossians 4:4-6 Paul not only lists the same three elements of rhetoric as Aristotle, but he lists them in the same order (which is suggestive of familiarity with Aristotle’s work):

Please pray that I will make the message as clear as possible. When you are with unbelievers, always make good use of the time. Be pleasant [ethos] and hold their interest [pathos] when you speak the message. Choose your words carefully and be ready to give answers to anyone who asks questions [logos]. (CEV)

There are even a few suggestive parallels between Paul’s writings and The Art of Rhetoric.[97] At the very least, Paul displays an implicit understanding of The Art of Rhetoric; and Paul’s Areopagus speech provides a model of using good rhetoric to communicate the gospel.[98]

Paul came to Athens as a herald of Christian spirituality.[99] Like all spiritualities, Christianity has a three-fold structure encompassing faith – i.e. a heart attitude of trust (in Jesus) mediated by certain worldview beliefs – and works. Paul believed that Christian spirituality is true, beautiful and good. He thus desired to persuasively communicate Christian spirituality to the Pagan Athenians. As a pre-requisite to this task, Paul studied and analysed different Athenian spiritualities (i.e. polytheistic, Stoic and Epicurean spiritualities). In each case he sought to affirm what was true and beautiful and good in these spiritualities in order to discover common ground with his audience; but he also noted things he judged as false, ugly or bad.[100] Having done his homework (so to speak) Paul ‘took the roof off’ of Athenian spirituality and gave his apologia for Christian spirituality, making good use of ethos, pathos and logos. Let’s briefly review Paul’s rhetoric in each of the three rhetorical categories:

In terms of ethos – Paul displayed a deep interest in and understanding of his audience’s spirituality (including their worldviews and cultures [101]). He ‘looked carefully at [their] objects of worship.’ (Acts 17:23) Then, as Darrell L. Bock observes, ‘despite being aggravated by all the idolatry he sees around him in Athens, Paul manages to share the gospel with a generous but honest spirit... Both message and tone are important in sharing the gospel. Here Paul is an example of both.’[102] Even Paul’s opening manner of address – ‘Men’ followed by the designation ‘Athenians’ (Acts 17:22) – was ‘thoroughly Greek’,[103] putting his audience at ease (cf. 1 Corinthians 9:22). Paul’s willingness to engage with Greek culture bore fruit in his masterful use of the altar ‘To an unknown god’ [104] and citations by memory (the rhetorical tool of anamnesis) [105] from several Greek writers. The examples he used to develop his theology of God were shared beliefs with the Stoics in the audience.[106] Paul went as far as he could in agreeing with his audience before critiquing their views. Whatever the terminology – ‘taking the roof off’ or ‘worldview analysis’ – this approach, which seeks to understand those to whom the gospel is being offered and to meet them on common ground, clearly underlies Paul’s critique of the Polytheistic, Epicurean and Stoic worldviews. Such an approach exhibits a truly Christian ethos. Contemporary apologists should likewise take a serious interest in the spirituality and culture of those with whom they wish to engage.

In terms of pathos – Paul engaged with certain of his audience’s religious piety and feelings of fear at a failure to be sufficiently pious – as revealed by the altar ‘to an unknown god’. He also exploited (artistically expressed) points of agreement and disagreement with and between the Stoic and Epicurean philosophers, as well as between both philosophies and the polytheistic religion of the state. Both philosophical schools had accommodated themselves to polytheism. Paul’s call to a consistent monotheism had uncomfortable socio-political ramifications for his audience. Contemporary apologists should likewise address people’s felt needs and seek lovingly to engender a spiritual ‘cognitive dissonance’, affirming truth, goodness and beauty in alternative spiritualities without flinching from critiquing falsehood, evil and ugliness therein (the apologist must not be cowed by the demands of ‘political correctness’).

Although Paul connected with his audience through ethos and pathos, he placed great emphasis upon issues related to logos and worldview (albeit as expressed in the beauty of Greek art and the practices of Greek religious culture). In terms of logos – Paul engaged with the natural theology of his audience, discussed historical revelation and presented evidence for Jesus’ resurrection. Contemporary apologists should likewise use philosophical and evidential arguments to provide rational confirmation of Christian spirituality, respond to criticisms of Christian spirituality and press criticisms against non-Christian spiritualities.

In sum, Paul exhibits an apologetic methodology that first compares and contrasts Christian and non-Christian spiritualities in terms of their truth, beauty and goodness before using the central elements of classical rhetoric to convince interested parties to embrace the spirituality of ‘the way’ based upon its superior merits in each transcendental category. The Pauline example of apologetics (as presented by Luke in Acts 17) thus exhibits the three-dimensional approach to communicating the gospel that I am calling apologetics ‘in 3D’,[107] and which is captured by the following matrix:

This matrix does not constitute an ‘argumentative strategy’, nor a step-by-step apologetic methodology, but rather an integrated conceptual framework for apologetics.[108] I am not suggesting that the apologist begin at the level of beliefs communicated by logos and judged by the standard of truth before moving on to deal in pathos, etc. I am suggesting that the apologist bear in mind the fact that, whether they are dealing with a query about truth or an objection about the behaviour of Christians, everything included within this matrix is related to everything else, and that it is therefore just as much of a mistake for the apologist to focus upon narrowly academic issues of truth at the expense of attitudes and actions as it would be to focus upon attitudes and actions without any reference to truth.

It is only in embracing such a holistic vision of their divinely appointed apologetic calling that Christians can joyfully rise to meet the contemporary missional challenge laid out by Alister McGrath:

If Christianity is to regain the imaginative ascendency, it must recover what G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936) termed ‘the romance of orthodoxy’. It is not sufficient to show that orthodoxy … has been tried and tested against its intellectual alternatives… The real challenge is for the churches to demonstrate that orthodoxy is imaginatively compelling, emotionally engaging, aesthetically enhancing, and personally liberating.[109]

Indeed, it is only in embracing this challenge that the church can fully embrace its own nature as the body of Christ, for we are called ‘to demonstrate and embody … the truth, beauty and goodness of faith.’[110]

Conclusion

Whilst recognizing the wisdom of building apologetic dialogue upon common ground, and the related importance of worldview analysis as an apologetic tool, I have argued that apologists should also keep the bigger picture of spirituality in mind. As Schaeffer explained: ‘The purpose of “apologetics” is not just to win an argument or a discussion, but that the people with whom we are in contact may become Christians and then live under the Lordship of Christ in the whole spectrum of life.’[111] With this goal in mind I have offered a holistic vision of apologetics as the art of persuasively advocating Christian spirituality across spiritualities, through the responsible use of classical rhetoric, as being objectively true, beautiful and good.[112]

References

[1] ‘Metapologetics refers to the study of the nature and methods of apologetics.’ – Kenneth D. Boa & Robert M. Bowman Jr., Faith Has Its Reasons: An Integrative Approach to Defending Christianity (Milton-Keynes: Paternoster, 2005), p.4.

[2] In advancing this definition I am not centrally concerned with the question of what Steven B. Cowan calls ‘argumentative strategy’ (i.e. the debate between classical, evidential, cumulative, presuppositional and reformed apologetic methodologies). Contemporary discussions of apologetic methodology have highlighted a measure of rapprochement between different argumentative strategies – cf. Steven B. Cowan (ed.), Five Views on Apologetics (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2000); Kenneth D. Boa & Robert M. Bowman Jr., Faith Has Its Reasons: An Integrative Approach to Defending Christianity (Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2005). I personally favour a broadly classical but cumulative method grounded in a reformed epistemology. cf. Peter S. Williams, A Sceptic’s Guide to Atheism (Milton Keynes; Paternoster, 2009); Understanding Jesus: Five Ways to Spiritual Enlightenment (Milton Keynes; Paternoster, 2011). Discussions about ‘argumentative strategy’ far from exhaust the range of issues falling under metapologetics, cf. Gregory E. Ganssle, ‘Making the Gospel Connection: An Essay Concerning Applied Apologetics’ in Come Let Us Reason: New Essays In Christian Apologetics (eds. Paul Copan & William Lane Craig; Nashville, Tennessee; B&H Academic, 2012); Sean McDowell (ed.), Apologetics For A New Generation (Eugene, Oregon: Harvest House, 2009); Scott R. Burson & Jerry L. Walls, C.S. Lewis & Francis Schaeffer: Lessons for a New Century from the most influential Apologists of Our Time (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP, 1998).

[3] Gregory E. Ganssle distinguishes between the ‘theological’, ‘academic’ and ‘missional’ themes of the apologetic enterprise, cf. ‘Making the Gospel Connection: An Essay Concerning Applied Apologetics’ in Come Let Us Reason: New Essays In Christian Apologetics (eds. Paul Copan & William Lane Craig; Nashville, Tennessee; B&H Academic, 2012).

[4] R.C. Sproul, John Gerstner & Arthur Lindsey, Classical Apologetics: A Rational Defence of the Christian Faith and a Critique of Presuppositional Apologetics (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1984), p.13.

[5] C. Stephen Evans, Pocket Dictionary of Apologetics & Philosophy of Religion (Leicester: IVP, 2002), p.12.

[6] Winfried Corduan, No Doubt About It: The Case for Christianity (Nashville, Tennessee; Broadman & Holdman, 1997), p.ix.

[7] James E. Taylor, Introducing Apologetics: Cultivating Christian Commitment (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2006), p.6.

[8] Francis J. Beckwith, ‘Introduction’ in To Everyone An Answer: A Case For The Christian Worldview (Francis J. Beckwith, William Lane Craig & J.P. Moreland eds.; Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP, 2004), p.13.

[9] John Frame, ‘Presuppositional Apologetics’ Five Views on Apologetics (Steven B. Cowan, ed.; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2000), p.215.

[10] William Lane Craig, Reasonable Faith: Christian Truth and Apologetics, Third Edition (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2008), p.15.

[11] Norman L. Geisler & Patrick Zukeran, The Apologetics of Jesus (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker, 2009), p.11.

[12] H. Wayne House & Dennis W. Jowers, Reason for Our Hope: An Introduction To Christian Apologetics (Nashville, Tennessee; Broadman & Holdman, 2011), p.2.

[13] Cf. William Lane Craig, ‘The Absurdity of Life Without God’.

[14] Taylor spends ten pages expanding upon his definition of apologetics, cf. An Introduction to Apologetics, pp.17-27.

[15] Gregory P. Koukl, ‘Tactics’ in To Everyone An Answer: A Case For The Christian Worldview (Francis J. Beckwith, William Lane Craig & J.P. Moreland eds.; Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP, 2004), p.55. cf. Gregory Koukl, Tactics: A Game Plan For Discussing Your Christian Convictions (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2009).

[16] Alister McGrath notes: ‘the New Testament [has a] tendency to mingle kerygma and apologia… both are essential components of the New Testament conception of the proclamation of Christ. The New Testament brings the two together in a creative and productive interplay: to proclaim the gospel is to defend the gospel, just as to defend the gospel is to proclaim the gospel.’ – Bridge Building, p.49. Douglas Groothuis urges: ‘The artificial separation of evangelism from apologetics must end… The apostle Paul serves as a model for us in that he both proclaimed and defended the gospel in the book of Acts… Jesus also rationally defended his views as well as proclaiming them.’ – ‘A Manifesto for Christian Apologetics: Nineteen Theses to Shake the World with the Truth’ in Reasons for Faith: Making A Case for Christian Faith (eds. Norman L. Geisler & Chad V. Meister; Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books, 2007), p.404. cf. Peter May, Dialogue in Evangelism (Grove, 1990); ‘What is Apologetics?’ & ‘Persuasion – the centre piece of effective evangelism’.

[17] Francis A. Schaefer, ‘The Undivided Schaeffer: A Retrospective Interview with Francis Schaeffer, September 30, 1980’ in Colin Duriez, Francis Schaeffer: An Authentic Life (Nottingham: IVP, 2008), pp.218 & 220.

[18] Cf. Robert Audi, Rationality and Religious Commitment (OUP, 2011).

[19] Douglas Groothuis, On Pascal (Thompson Wadsworth, 2003), p.41.

[20] Douglas Groothuis, Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith (Nottingham; Apollos, 2011), p.20.

[21] Ibid, p.29.

[22] Doug Powell, Holman QuickSource Guide to Christian Apologetics (Nashville Tennessee: Holman Reference, 2006), p.16.

[23] Cf. Francis A. Schaeffer, The God Who Is There (1968) in The Complete Works of Francis A. Schaeffer: A Christian Worldview – Volume 1: A Christian View of Philosophy and Culture (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books, 1994), pp.133-134, 135, 138, & 140-141. In a similar vein, Nick Pollard writes about the process of positive deconstruction: ‘The process is “deconstruction” because I am helping people to deconstruct (that is, take apart) what they believe in order to look carefully at the belief and analyse it. The process is “positive” because this deconstruction is done in a positive way – in order to replace it with something better… The process of positive deconstruction recognizes and affirms the elements of truth to which individuals already hold, but also helps them to discover for themselves the inadequacies of the underlying worldviews they have absorbed. The aim is to awaken a heart response that says, “I am not so sure that what I believe is right after all. I want to find out more about Jesus.”’ – Evangelism Made Slightly Less Difficult (Leicester: IVP, 1997), pp.41 & 44.

[24] ‘Cognitive dissonance is a theory of human motivation that asserts that it is psychologically uncomfortable to hold contradictory cognitions. The theory is that dissonance, being unpleasant, motivates a person to change his cognition, attitude, or behavior.’ – The Skeptic's Dictionary (2005).

[25] Boa & Bowman, Faith Has Its Reasons, p.xiii.

[26] E.g. Norman L. Geisler, Christian Apologetics (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker, 1995); Norman L. Geisler & William D. Watkins, Worlds Apart: A Handbook On World Views (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker, 1989); Arthur F. Holmes, Contours of a Worldview (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1983); Chad V. Meister, Building Belief: Constructing Faith from the Ground Up (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 2006); Ronald H. Nash, Worldviews In Conflict: Choosing Christianity In A World Of Ideas (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1992); James W. Sire, The Universe Next Door, fifth edition (Downers Grove: IVP, 2009).

[27] James W. Sire, The Universe Next Door, fifth edition (Downers Grove: IVP, 2009), p.17.

[28] D.A. Carson, ‘Athens Revisited’ in D.A. Carson (ed.), Telling the Truth: Evangelizing Postmoderns (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2000), p.398.

[29] Boa & Bowman, Faith Has Its Reasons, pp.89, 134 & 135.

[30] Cf. Footnote 26.

[31] Nash, Worldviews In Conflict, 16.

[32] Robert L. Reymond, Faith’s Reasons For Believing (Fearn, Ross-shire: Mentor, 2008), pp.25-26.

[33] McGrath, How Shall We Reach Them?, p.17.

[34] Alister E. McGrath, Mere Apologetics: How To Help Seekers & Skeptics Find Faith (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker, 2012), p.11. See also Michael Green & Alister McGrath, How Shall We Reach Them? Defending and Communicating The Christian Faith To Nonbelievers (Milton Keynes: Word, 1995).

[35] C.S. Lewis, ‘Christian Apologetics’ in Compelling Reason (London: Fount, 1996), p.78.

[36] Gregory E. Ganssle, ‘Making the Gospel Connection: An Essay Concerning Applied Apologetics’ in Come Let Us Reason: New Essays In Christian Apologetics (eds. Paul Copan & William Lane Craig; Nashville, Tennessee; B&H Academic, 2012), p.5.

[37] This advice is the implicit backbone of Norman L. Geisler’s Christian Apologetics (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker, 1995).

[38] Cf. J. Daryl Charles, ‘Engaging the (Neo)Pagan Mind: Paul’s Encounter with Athenian Culture as a Model for Cultural Apologetics (Acts 17:16-34),’ Trinity Journal, 16:1 (Spring 1995), pp.47-62; Lars Dahle, ‘Acts 17:16-34. An Apologetic Model Then and Now?’, Tyndale Bulletin 53.2 (2002), 313-316; ‘Acts 17 and the Biblical Basis for Apologetics’ (ELF, 2005); ‘Acts 17 as an apologetic model’, Whitefield Briefing, Vol. 7, No. 1 (March 2002) ‘Encountering and Engaging a Postmodern Context: Applying the apologetic model in Acts 17’, Whitefield Briefing, Vol. 7, No. 6 (December 2002); J.I. Packer, ‘Paul Against Pluralism’ in Tough-Minded Christianity: Honoring the Legacy of John Warwick Montgomery (William A. Dembski & Thomas Schirrmacher, eds.; Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Academic, 2008), pp.2-19.

[39] Cf. Julian Baggini, ‘You don’t have to be religious to pray’; Alain de Botton, Religion for Atheists (Hamish Hamilton, 2012); Robert C. Solomon, Spirituality for the Skeptic: The Thoughtful Love of life, new edition (Oxford University Press, 2006); Andre Comte-Sponville, The Book Of Atheist Spirituality: An Elegant Argument for Spirituality Without God (London: Bantam Press, 2008).

[40] Alexander W. Astin, Helen S. Astin & Jennifer A. Lindholm, Cultivating the Spirit: How College Can Enhance Student’s Inner Lives (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2011), p.4.

[41] Unless otherwise specified, all scriptural quotations are from the TNIV.

[42] Perry G. Downs, Teaching For Spiritual Growth (Zondervan, 1994), p.25.

[43] This definition correlates with the schema undergirding Cognitive Behavioural Therapy: ‘CBT can help you to make sense of overwhelming problems by breaking them down into smaller parts… These parts are: A Situation – a problem, event or difficult situation. From this can follow: Thoughts, Emotions, Physical feelings, Actions. Each of these areas can affect the others. How you think about a problem can affect how you feel physically and emotionally. It can also alter what you do about it.’ See here. Cf. Lawrence J. Crabb, Effective Biblical Counselling: How to become a capable counsellor (London: Marshall Pickering, 1990), especially chapter five. See also Josh McDowell, ‘A Relevant Apologetic’ in Reasons for Faith: Making A Case for the Christian Faith (Norman L. Geisler & Chad V. Meister eds.; Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2007), pp.27-39 & Sean McDowell, ‘Apologetics For An Emerging Generation’ in Passionate Conviction: Contemporary Discourses on Christian Apologetics (eds. Paul Copan & William Lane Craig; Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Academic, 2007), pp.258-271; Abigail James & Adrian Wells, ‘Religion and mental health: Towards a cognitive-behavioural framework’, British Journal of Health Psychology, Volume 8, Issue 3 (September 2003), pp.359-376.

[44] It’s worth remembering that the pre-requisite of tolerance is the belief that what one is tolerating is wrong (but to be admitted to the intellectual marketplace nonetheless). It is the self-contradictory postmodern rejection of the belief that mutually contradictory beliefs cannot all be true that is the quintessentially intolerant spirituality, because it seeks to exclude everything beside itself from the intellectual marketplace.

[45] David Naugle, Worldview and Church: An Interview with David Naugle.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Sire, The Universe Next Door, fifth edition, p.20.

[48] Glen Schultz, Kingdom Education (Nashville: LifeWay Press, 1998), p.39.

[49] J.P. Moreland, Love Your God With All Your Mind (Colorado Springs: Navpress, 1997), p.73.

[50] Cf. Douglas Groothuis, Truth Decay: Defending Christianity Against The Challenges Of Postmodernism (Leicester: IVP, 2000); J.P. Moreland, ‘What is Truth?’.

[51] Moreland, Love Your God With All Your Mind, p.74.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid, p.75.

[54] Cf. James W. Sire, Why Should Anyone Believe Anything At All? (Leicester: IVP, 1994), p.22.

[55] Cf. Peter S. Williams, ‘Understanding the Trinity’.

[56] What Bill Smith says of Christian spirituality actually goes for all spiritualities: ‘Biblical spirituality is holistic in the truest sense. It encompasses reason and feeling… we need to proclaim and live a ... Christianity that integrates the mind (orthodoxy), the heart (orthopathy) and the hands (orthopraxy).’ – ‘Blazing the North-South Trail’, Just Thinking, Winter 2001, p.11.

[57] In point of fact, Mark 12:30 reads: ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart [kardia] and with all your soul [psyche] and with all your mind [dianoia] and with all your strength [ischus].’ However, Mark includes the response to Jesus’ answer from the scholar who prompted it: ‘we must love God with all our heart, mind, and strength.’ (Mark 12:33) In Matthew 22:37 Jesus says: ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind’. In Luke 10:27 Jesus says: ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind.’ While the synoptic gospels present us with the authentic voice of Jesus, they don’t present us with his precise words here (indeed, in Luke it isn’t Jesus, but the teacher of the law, who is quoted). However, in each case there’s a clear reference to Deuteronomy, which contains the tripartite command to ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength.’ (Deuteronomy 6:5, cf. Joshua 22:5) We may take ‘soul’ here as synonymous with ‘mind’, although ‘soul’ can be used to refer to the specific capacity of the human mind or spirit to relate to God (cf. Psalm 42:1-2, Psalm 103:2). It may be that ‘heart’ and ‘soul’ were paired by Jesus in the sense of ‘I love you heart and soul’ (i.e. ‘with all that I am’), while ‘strength’ and ‘mind’ were pared to suggest both the inner (mind) and outer (strength) aspects of a person’s life. R. Laird Harris et al comment: ‘McBride observed: “The three parts of Deut 6:5: lev (heart), nephesh (soul or life), and meod (muchness) … were chosen to reinforce the absolute singularity of personal devotion to God. Thus lev denotes the intention or will of the whole man; nephesh means the whole self, a unity of flesh, will, and vitality; and meod accents the superlative degree of total commitment to Yahweh.”... The NT struggles to express the depth of the word meod… In the quotation in Mk 12:30 it is rendered “mind and strength,” in Lk 10:27 it is “strength and mind,” in Mt 22:37 simply “mind”.’ – Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1999), 487 – ‘How did “mind” get into the Shema?’ see here. Because Jesus refers to both the heart and the mind/soul, I use ‘heart’ in a slightly narrower sense than that used by Naugle and Sire (who use the term to refer to both ‘the heart’ and ‘the mind’). Jesus’ God-centred principle commandment is of course immediately and organically followed by the self-and-other-centred command to ‘love your neighbour as yourself’ (Mark 12:31 & 33, cf. Leviticus 19:18).

[58] ‘Peter is calling us not simply to a rational, one-dimensional response that addresses the intellect of the listener, but rather to a full-orbed apologetic that engages the entire person: mind, will and emotions… what Peter offers us here in the classic apologetic text is a vision of a thoroughly integrated, holistic apologetic.’ – Scott R. Burson & Jerry L. Walls, C.S. Lewis & Francis Schaeffer: Lessons for a New Century from the most influential Apologists of Our Time (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP, 1998), pp.251-252.

[59] The context of Paul’s discussion puts the emphasis on the heart-attitude of the Colossians; but it’s clear that this attitude is formed in response to a strong and specific knowledge of the word (logos) of Christ, and that the appropriate attitude to this word (i.e. not only Christ’s teachings, but to the very person of Christ who makes them ‘one body’) results in actions reflecting the nature (‘in the name’) of Christ.

[60] Cf. Peter S. Williams, ‘Blind Faith in Blind Faith’.

[61] C.E.M. Joad, The Recovery of Belief (London: Faber, 1952), pp.16-17.

[62] Koukl, Tactics, p.25.

[63] Elizabeth A. Dreyer & John B. Bennett, Spirituality in Health and Education Newsletter, Volume 3, issue 1, September 2006.

[64] Cf. Charles Colson & Nancy Pearcey, How Now Shall We Live? (London: Marshall Pickering, 1999), pp.307-316; Theodore J. Chamberlain & Christopher A. Hall, Realized Religion: Research on the Relationship between Religion and Health (London: Templeton Foundation Press, 2000); Mark Baker & Richard Gorsuch, ‘Trait Anxiety and Intrinsic-Extrinsic Religiousness’, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Jun., 1982), pp.119-122; Tara Joy Cutland, ‘Intrinsic Christianity, Psychological Distress and Help-Seeking’, PhD Thesis, University of Leeds (2000); Kelly Furr et al, ‘Effects of L.D.S. Doctrine vs. L.D.S. Culture on Self-Esteem’

[65] Steve Fuller, The Intellectual (Cambridge: Icon, 2006), p.27.

[66] This goal is, of course, not unique to Christian apologetics. For an examination of Christian spirituality in the context of Jesus studies, cf. Peter S. Williams, Understanding Jesus: Five Ways to Spiritual Enlightenment (Paternoster, 2011). See also: Charles Colson & Nancy Pearcey, How Now Shall We Live? (London: Marshall Pickering, 1999); J.P. Moreland, Kingdom Triangle (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2007); (Audio CD) John Mark Reynolds, Contending for the Christian Worldview (Christian Apologetics: Biola University).

[67] Alister McGrath, How Shall We Reach Them? Defending and Communicating The Christian Faith To Nonbelievers (Word, 1995), p.18.

[68] Aristotle, The Art of Rhetoric (Trans H. C. Lawson-Tancred; London: Penguin, 2004), p.70.

[69] Aristotle, The Art of Rhetoric, p.80.

[70] Ibid, p.74.

[71] For an introduction to rhetoric cf. Joe Carter & John Coleman, How To Argue Like Jesus: Learning Persuasion From History’s Greatest Communicator (Wheaton, Illinois; Crossway, 2009).

[72] Cicero, Orator: 75, quoted by H. C. Lawson-Tancred, The Art of Rhetoric (London: Penguin Classics, 1991), p.55.

[73] Stratford Caldecott, Beauty for Truth’s Sake: On the Re-enchantment of Education (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2009), p.31.

[74] Kreeft, ‘Lewis’ Philosophy of Truth, Goodness And Beauty’ in C.S. Lewis as Philosopher, p.33.

[75] E.g. Peter S. Williams, I Wish I Could Believe in Meaning: A Response to Nihilism (Southampton: Damaris, 2004) & A Faithful Guide to Philosophy: A Christian Introduction to the Love of Wisdom (Forthcoming – Paternoster, 2013).

[76] Cf. Psalm 27:4: ‘One thing I asked of Jehovah – it I seek. My dwelling in the house of Jehovah, All the days of my life [goodness], To look on the pleasantness of Jehovah [beauty], And to inquire in His temple [truth].’ (Young’s Literal Translation) & Philippians 4:8: ‘whatever is true, whatever is noble [i.e beautiful], whatever is right [i.e. good]…’ (TNIV).

[77] Cf. John Cottingham, ‘Philosophers are finding fresh meanings in Truth, Goodness and Beauty’, The Times (June 17, 2006); Steven B. Cowan & James S. Spiegel, The Love of Wisdom: A Christian Introduction to Philosophy (Nashville, Tennessee: B&H, 2009); Thomas Dubay, The Evidential Power of Beauty: Science and Theology Meet (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1999); Douglas Groothuis, Truth Decay: Defending Christianity Against The Challenges Of Postmodernism (Leicester: IVP, 2000); Peter Kreeft, ‘The True, the Good and the Beautiful’ & ‘Lewis’ Philosophy of Truth, Goodness And Beauty’ in C. S. Lewis as Philosopher: Truth, Goodness and Beauty (Downers Grove: IVP, 2008); C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (London: Fount, 1999); Michael P. Lynch, True To Life: Why Truth Matters (London: MIT, 2004); Colin McGinn, Ethics, Evil and Fiction (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999); Roger Scruton, Beauty (Oxford University Press, 2009); Joseph D. Wooddell, The Beauty of Faith: Using Aesthetics for Christian Apologetics (Wipf & Stock, 2010).

[78] J.L. Mackie, Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong (London: Penguin, 1990), p.15.

[79] G.E. Moore, Principia Ethica (Cambridge University Press, 1993), p.249.

[80] Cf. Francis J. Beckwith & Gregory Koukl, Relativism; Feet firmly planted in mid-air (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1998); Francis J. Beckwith, ‘Why I am Not A Moral Relativist’; Paul Chamberlain, Can We Be Good Without God? (Downers Grove: IVP, 1996); Steven B. Cowan & James S. Spiegel, The Love of Wisdom: A Christian Introduction to Philosophy (Nashville, Tennessee: B&H, 2009); Michael Huemer, Ethical Intuitionalism (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007); Greg Koukl, ‘The Bankruptcy of Moral Relativism’ ; Greg Koukl vs. John Baker, ‘Do Moral Truths Exist?’; Peter Kreeft, ‘A Refutation of Moral Relativism’; Russ Shafer-Landau, Whatever Happened to Good and Evil? (Oxford, 2003); C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (London: Fount, 1999); Peter S. Williams, ‘Can Moral Objectivism Do Without God?’.

[81] A.N. Wilson quoted by Robin Phillips, ‘The Devotion of J.S. Bach’.

[82] Cf. Bach: St Matthew Passion [3 CD Box Set] (Naxos, 2006).

[83] Cf. Peter Kreeft, ‘Introduction’ in Does God Exist? The Debate Between Theists & Atheists (New York: Prometheus, 1993), p.27 & ‘The Rationality of Belief in God’.

[84] Cf. The Last Judgment (van der Weyden).

[85] Peter Hitchens, The Rage Against God (London: Continuum, 2010), p.75.

[86] Alister McGrath, Mere Apologetics: How to Help Seekers & Skeptics Find Faith (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker, 2012), pp.127-128. Cf. Everett Berry, ‘Interview with Joseph D. Wooddell’ .

[87] For background cf. Darrell L. Bock, Acts (Baker Exegetical Commentary On The New Testament, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker, 2007); Brian Godawa, ‘Storytelling and Persuasion’ in Apologetics For A New Generation: A Biblically & Culturally Relevant Approach to Talking About God (ed. Sean McDowell; Eugene, Oregon: Harvest House, 2009); I. Howard Marshall, Acts (Tyndale New Testament Commentary, IVP Academic, 2008); Bruce W. Winter, ‘On Introducing Gods To Athens: An Alternative Reading Of Acts 17:18-20’, Tyndale Bulletin 47:1 (May, 1996), pp.71-90; Bruce W. Winter, ‘In Public and in Private: Early Christians and Religious Pluralism’, One God, One Lord: Christianity in a World of Religious Pluralism, 2nd edition (eds. Andrew D. Clarke & Bruce W. Winter; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker, 1992) and Ben Witherington III, The Acts of the Apostles: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1998). For archaeological background cf. John McRay, Archaeology & the New Testament (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 1991), pp.298-310. For philosophical background cf. John Mark Reynolds, When Athens Met Jerusalem: An Introduction to Classical and Christian Thought (Downer’s Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic, 2009).

[88] H. Wayne House, ‘A Biblical Basis for Balanced Apologetics’ in Reasons for Faith: Making A Case for Christian Faith (eds. Norman L. Geisler & Chad V. Meister; Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2007), p.69.

[89] House notes: ‘it is this council before whom Socrates also appeared and was sentenced to death for introducing to the youth of Athens strange deities... Luke may even be attempting to draw some parallel between Socrates and Paul.’ – ‘A Biblical Basis for Balanced Apologetics’, p.71. Cf. Charles, ‘Engaging the (Neo)Pagan Mind’, p.53; Witherington, The Acts of the Apostles, pp.514 & 525-526. The rectitude of metapologetic appeals to Acts 17 can be substantiated with reference to the overall apologetic nature of Acts, the exemplary nature of speeches in Acts and Paul’s socio-rhetorical context. Cf. Clinton E. Arnold, Acts, p.6; Charles, ‘Engaging the (Neo)Pagan Mind’, p.49; Dahle, ‘Acts 17 as an apologetic model’; I. Howard Marshall, Acts, pp.20-25 & pp.298-299; Bruce Winter, ‘Introducing the Athenians to God: Paul’s failed apologetic in Acts 17?’.

[90] Ivor Bulmer-Thomas, ‘St. Paul the Missionary’, St. Paul: Teacher and Traveller (ed. Ivor Bulmer-Thomas; Leighton Buzzard: The Faith Press, 1975), p.50. Bulmer-Thomas muses that ‘the books’ mentioned by Paul in 2 Timothy 4:13 ‘could have included Greek works.’ – St. Paul: Teacher and Traveller, p.76.

[91] Charles, ‘Engaging the (Neo)Pagan Mind’, p.50.

[92] Francis Clark, ‘St. Paul the Man’, St. Paul: Teacher and Traveller (ed. Ivor Bulmer-Thomas; Leighton Buzzard: The Faith Press, 1975), p.19.

[93] Cf. Charles, ‘Engaging the (Neo)Pagan Mind’, p.50.

[94] A deliberative speech aims to change an audience’s spirituality at one or more levels. For a detailed rhetorical analysis of Paul’s speech, cf. Witherington, The Acts of the Apostles, pp.517-532.

[95] ‘to belong to Gamaliel’s school, as Paul did, was no small thing. The Torah claims that Gamaliel had 500 young men in his “house” who studied the Torah and 500 who studied Greek wisdom... Here is a window into two seemingly impossible groups of scholars, one studying the Torah in Hebrew and the other studying the classical texts of the Greeks in their language.’ – Paul Barnett, Paul: Missionary of Jesus (Cambridge: Eerdmans, 2008), p.35.

[96] David Wenham, Paul and Jesus: The True Story (London: SPCK, 2002), p.3.

[97] Compare Aristotle, The Art of Rhetoric (Trans. H. C. Lawson-Tancred; London: Penguin Classics, 2004), chapter 1.9:105 with Philippians 4:8 on ‘the noble’ and The Art of Rhetoric, chapter 1.13:125 & chapter 1.15:130 with Romans 2:14-15 on the universal unwritten moral law.

[98] Cf. Larry W. Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ – Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans/Cambridge, 2003), p.90. Paul did of course repudiate the sort of bad rhetoric and ethics with which the ‘sophists’ have forever been associated by Socrates and Plato – cf. Winter, ‘Introducing the Athenians to God: Paul’s failed apologetic in Acts 17?’; ‘The Entries and Ethics of Orators and Paul (1 Thessalonians 2:1-12)’, Tyndale Bulletin 44.1 (1993), pp.55-74.

[99] Cf. Winter, ‘On Introducing Gods To Athens: An Alternative Reading Of Acts 17:18-20’.

[100] N.B. Stonehouse comments: ‘To conclude that Paul had no eye whatsoever for the beauty that surrounded him as he strode about the city would be rash and gratuitous. Nevertheless … the gigantic gold and ivory statue of Athena in the Parthenon on the Acropolis, for example, could not be viewed by Paul simply as a thing of beauty. The fact that it was an idol stirred Paul far more profoundly than its aesthetic merits.’ – ‘The Areopagus Address: The Tyndale New Testament Lecture 1949’. I’d say that such epistemic and moral failings are simultaneously aesthetic failings; cf. Williams, I Wish I Could Believe in Meaning.

[101] A ‘culture’ is a specific corporate spirituality (i.e. a more-or-less coherent set of shared worldview beliefs, attitudes and ways of behaving) and its characteristic artistic tradition/s, broadly construed.

[102] Bock, Acts, p.573.

[103] Charles, ‘Engaging the (Neo)Pagan Mind’, p.54.

[104] Cf. Marshall, Acts, pp.302-303; Witherington, The Acts of the Apostles, pp.521-523. Bruce W. Winter notes that: ‘Whether [Paul] actually saw the divine title in the plural or the singular would have been of no importance to his audience, for the terms “god” and “gods” could be used interchangeably by Stoics and Epicureans in the same sentence.’ – ‘In Public and in Private: Early Christians and Religious Pluralism’, One God, One Lord, pp.128-129. Peter Kreeft suggests that, as a poor stonecutter accused of worshipping an unknown God, it may be that Socrates himself was responsible for the inscription Paul found. Cf. Peter Kreeft, ‘Making Sense Out of Suffering’ in Socrates In The City: Conversations On ‘Life, God & Other Small Topics’ (ed. Eric Metaxas; London: Collins, 2011), p.62.

[105] ‘Anamnesis helps establish ethos since it conveys the idea that the speaker is knowledgeable of the received wisdom from the past.’ – Joe Carter & John Coleman, How To Argue Like Jesus: Learning Persuasion From History’s Greatest Communicator (Wheaton, Illinois; Crossway, 2009), p.72. Cf. Bock, Acts, p.586; Witherington, The Acts of the Apostles, pp.529-530.

[106] Cf. House, ‘A Biblical Basis for Balanced Apologetics’, pp.73-74; Winter, ‘In Public and in Private: Early Christians and Religious Pluralism’, One God, One Lord, p.133.

[107] As did Jesus’ own ministry, cf. Carter & Coleman, How To Argue Like Jesus.

[108] This conceptual matrix can be fruitfully employed within any discipline that deals with understanding and / or expressing and / or assessing human responses to reality, e.g. education (cf. Peter S. Williams, 'A Vision For Spiritual Education') or media studies (cf. Peter S. Williams, ‘Viewing Spiritual Worlds Through Film’).

[109] Alister McGrath, Heresy (London: SPCK, 2009), pp.233-234.

[110] Alister McGrath, The Passionate Intellect: Christian Faith and the Discipleship of the Mind (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP, 2010), p.93.

[111] Schaeffer, The Complete Works of Francis A. Schaeffer: A Christian Worldview – Volume 1, p.153.